The Celebrity Shrink and the Ghost

When Americans revered Dr. Joyce Brothers, my mother ghostwrote her column--and burned with resentment.

When Dr. Joyce Brothers died at 85 after more than half a century of fame as a TV psychologist, bestselling author and audience favorite on the talk show circuit, my first thought was of my mother.

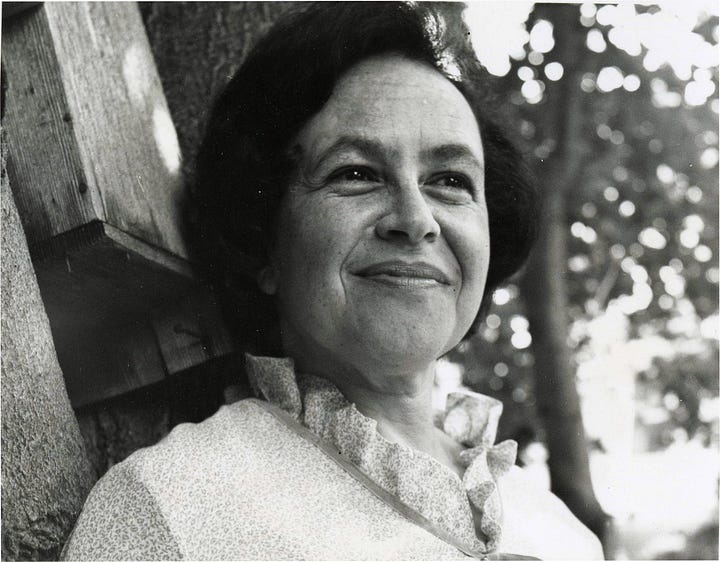

Fredelle Maynard—formidably accomplished, widely published but never a household name—used to ghostwrite Dr. Brothers’ column in Good Housekeeping. It paid $400 a shot, a tidy sum in the late 60s, but my mother disdained the work. In her youth she had talked Art and Life with the best (the fellow known as Vlad went on to write Lolita). Now fate had reduced her to burnishing another woman’s image—a woman she deemed unworthy of her craft.

Joyce Brothers and Fredelle Maynard were sisters of a kind. Both Jewish, both Depression daughters, although Joyce had the edge on social class (her parents were lawyers; my mother’s barely scraped by as shopkeepers). Both ablaze with ambition, they navigated sexism and anti-Semitism to win doctorates (Joyce from Columbia, Fredelle from Radcliffe) at a time when Jews and women were suspect in academe.

Fredelle turned to writing when she couldn’t land a teaching post, despite her many academic honors. Joyce was told, early on, to “go home and be a good wife.” With a small daughter and a husband completing his medical internship, she couldn’t afford that life even if she wanted it. But she and Milton Brothers believed they could cash in on Joyce’s phenomenal memory. She’d make herself an expert on some arcane subject and compete on a wildly popular quiz show, The $64,000 Question. She and Milton considered plumbing but settled on boxing. Who’d believe that a slight, demure psychologist knew all there was to know about blood, fists and muscle?

“Sisterhood is powerful,” we said as I came of age. I wouldn’t call it a fiction. But when women must compete for money and clout on hostile turf, the triumph of one can seem an affront to another. My mother’s total recall of the English canon was a legend among everyone who studied with her or sat at her table. To every conversation she added a fillip of verse. If not for her horror of quiz shows, could she have hit the jackpot on 17th-century poetry?

Joyce crammed for the show with expert coaches, a former boxing champion and the editor of Ring magazine. Her tenacity paid off. At 28, she captured the grand prize. The New York Times would say in her obituary, “Dr. Brothers was able to transform a single night—December 6, 1955, the night of her $64,000 question—into more than five decades of celebrity.”

Dr. Joyce Brothers was a brand before anyone applied the term to humans. She appeared everywhere from bookstore shelves to movie screens, playing her coiffed and unflappable self. She’d fly anywhere to appear on TV because that’s what it took to ensure her place among America’s 10 Most Admired Women. At such a pace, she didn’t sweat the details of her column for Good Housekeeping. Details were the ghostwriter’s business.

Dr. Fredelle Maynard set great store by erudition. She never interviewed a doctor without using her academic title and reading all the relevant literature. One marveled, to her impish delight, “Are you a urologist?” Dr. Joyce Brothers hobnobbed on TV with the likes of Sonny and Cher. She called herself “a psychological journalist,” but to Fredelle she was a mere assembler of clippings. My mother spun the argument, embellished with a sprinkling of quotations (Updike, Auden, Lorca). She joked that the magazine’s monthly photo of Joyce perusing research should include herself looking out of the file drawer. To manage her resentment, she turned it into comic set pieces. From one of the letters that contain her most vivid writing:

“Today is Joyce Brothers day. I set aside about 12 hours a month when I can sift through the masses of stuff dispatched by her clipping bureau and her own garbled and vulgar notes. Ugh. I feel almost as if I should have a special costume for the work, something like those suits worn to protect against radioactivity, and a pair of long-handled tongs. It is contaminating, and for nothing less than a lot of money would I do it. Now there’s a pure sentiment. Fortunately, I’m still able to appreciate the comedy. Last week she phoned, just a little ruffled, to say that she’d mistaken the exact subject when she wrote her ‘point of view,’ so would I please make any necessary adjustments? When the package came, I saw that she’d written on Why Women Like Pornography. But the topic GH wanted was Why Women Are Turned Off By Pornography. Adjustment indeed. I invented everything, thanking my luckful stars the while that the situation hadn’t been reversed.”

Deadlines, to Fredelle, were up there with Updike and Auden. To Joyce, they meant nothing a promise couldn’t fix. A monthly blizzard of calls would ensue between the ghost, the icon and the frantic editor at GH: “Ask Joyce.” “She says she mailed it two days ago.” And finally, icon to ghost in what Fredelle described as a “little-girl, sweet, breathy” voice: “Gosh, hon, I’m sorry. I put it in the mail this afternoon.” On Fredelle’s list of grievances against Joyce, “hon” was number nine-hundred-and-something.

Some of Joyce’s advice appalled my mother. One draft included the suggestion that a woman neglected by her husband should take a good look in the mirror. But there’s a reason why the public revered Dr. Joyce Brothers. When psychotherapy carried a taint and nice people didn’t speak of mental illness, she started ground-breaking conversations. She talked on TV about premature ejaculation (one man said she changed his life). When Milton’s death shattered her, she considered suicide—and told the truth in a book, Widowed. A man with her academic credentials would likely have become a professor and retired to play golf. Not Joyce. She’d achieved everything she wanted—fame, money, a chance to make a difference. She wasn’t about to let it go.

My mother would have relished even a shard of Joyce’s glory, but what really stung was more profound than envy—the sacrifice of her storytelling powers. “Ghost” comes from an Old English word for “spirit” or “soul,” and my mother had lost touch with both. She wrote in a plaintive letter to my sister, “I do want somehow to catch and hold certain important experiences of my life and turn them into very little works of art. You see, I spend most of my time playing special roles—I am your mother, Daddy’s wife, Grandma’s child, Linda’s teacher, and so on. And each of these roles involves time and responsibility. I feel a need to be, even for a little while, just me. And I would like to write some things that express the me-ness of me, as well and as truly as possible.”

She did, in the end, put the Fredelleness of Fredelle on the page. Decades after her death, I still hear from readers who recognize a little of themselves in her two memoirs, Raisins and Almonds and The Tree of Life, both long out of print. One day my son may hear similar remarks about me.

I forget which distinguished writer once described himself, too modestly, as “an honest minor writer.” An honest minor writer is all most writers will ever be. Talk shows won’t court us and the zeitgeist will pass us by. But when one honest writer homes in on the me-ness of me, readers are stirred by the us-ness of us. I’ve yet to meet a writer who wouldn’t prefer 5 million readers to 50. Even so, 50 readers aren’t nothing. Think about it: 50 hearts, 50 minds, 50 pairs of hands.

I’m my mother’s daughter. I keep the faith.

And now let the conversation begin! From psychology in the media to the struggles of ambitious women, the pursuit of fame to the value of writing the you-ness of you, this is the place to have your say. I do my best to answer every comment, and I love it when you keep me scurrying to catch up.

If you’ve been enjoying Amazement Seeker, here are four ways to spur me on:

Click “like.” The Substack algorithm looks for hearts.

Share this post.

Leave a comment (it bears repeating).

If you’re feeling generous, consider a paid subscription. Simmering away on my back burner: my first writing workshop for paid subscribers. We’ll look closely at a talismanic essay by Andre Dubus that informed and inspired one of my most popular posts, “Here I Am.”

Dr. Joyce Brothers deserves a full-fledged biography that explores both her character and her impact. For now the best resource is Kathleen Collins’ workmanlike cultural study, Dr. Joyce Brothers: the Founding Mother of TV Psychology, free to read at The Internet Archive. As for Fredelle Maynard, lots of you have met her a time or two. New friends can find more stories here, here and here. Oh, and I’ve written a memoir, My Mother’s Daughter. See you in Comments.

I never appreciated Joyce Brothers's public persona. I found her a little condescending and off-putting, not someone I would ever appeal to for advice. This is just in response to her media presence. Not exactly sure why, and I don't really think it matters. I never read her column...and now, knowing this about your mother, I'm feeling regret. I want to read it now! It still boggles my mind that women have had to fight so hard to claim our place in the world. I became a feminist when I was in kindergarten. It didn't seem complex to me, it was common sense that we are, whatever our gender, equals to one another. I'm glad your Mom knew her own worth, that's not often the case with many who work so hard for the things that fulfill them. I hope she had satisfaction in what she was able to accomplish given the constraints of her era. I just ordered a copy of Raisins and Almonds. Looking forward to reading it. xoxo

Oh, she absolutely knew she was exceptional. Wherever she studied on the way to her Radcliffe doctorate, she quickly established herself as the star. She had the awards, the recommendations, the Phi Beta Kappa key—but not a penis.