Love, Sex and the Cleaning Woman

Love always puts a lover to the test. How far can a woman go for an adoring man who asks the unthinkable of her?

When my mother was 53, newly divorced and convinced no man would look at her again, a stranger called to announce himself: Sydney Bacon of Toronto, ardent fan of her first book. Could he take her to dinner in New York? He’d caught her mid-paragraph at her desk in New Hampshire. New York was not in her sights. Well then, countered Sydney in a booming voice. He would come to dinner at her house in Durham.

This news made me shiver with prudish dismay. “You invited a stranger to your house?” The wine, the expectations, the double bed where she had slept alone pretty much her entire married life. My mother giggled like a smitten teenage girl. Sydney Bacon was a consequential man, a successful importer of basketware. Fredelle Maynard had a houseful of baskets, and Canadians were loving Sydney's. Wicker had made him lots of money. And by a stroke of luck ,he was Jewish. Her marriage to my gentile father, proud son of the British Raj, had broken the hearts of her parents.

My sister and I tut-tutted, but nothing could stand between my mother and her suitor. The Basket Millionaire, as we called him, was on his way to Fortress Fredelle like a wayward sexagenarian prince, about to thump the brass knocker.

My mother welcomed Sydney in a navy blue suit, buttoned to the chin. She served salmon mousse with dill sauce, an Amy Vanderbilt recipe that struck the balance between safe and stylish. It arrived on the table all aquiver, an olive-eyed, curlicued fish newly sprung from a faux-copper mold and resting on a bed of cottage cheese. How many times had I seen her plate that mousse at dinner parties? The recipe sat in my card file, handwritten with a flourish in ballpoint pen. I shouldn’t miss a deal on canned salmon, she said. That mousse never fails a cook.

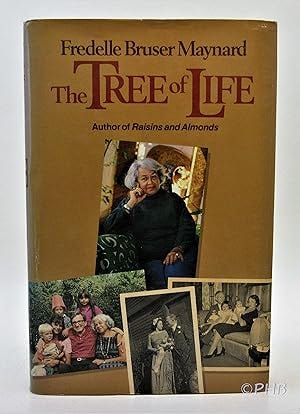

Sydney spent the night at his hotel, returning for a bright-and-early breakfast. My mother wore her white hostess gown with a cascade of ruffles down the front. As she was beating eggs, he placed his hands on her shoulders and said, "I'm baffled. I heard your voice in the book. Where are you?" She described the moment in her second memoir, The Tree of Life:

"When I began to cry, he sat me down on the living-room couch and said, 'Tell me about your marriage.' Though I told him very little—he was, after all, a stranger—he made a swift intuitive leap. 'My goodness, you really are a virgin, aren't you?' 'I have two children,' I sniffed. He didn't comment. Then he said, 'Would you come upstairs and lie down on the bed with me?' 'Certainly not,' I said. 'I promise I won't touch you if you don't want me to,' he said. 'I'd like us to relax and talk.'.... I had scarcely arranged myself decorously on top of the bedspread when Sydney Bacon walked in—wearing nothing at all. 'Have you never seen a naked man before?' he asked—and then, when I remained silent, 'I thought not.'"

Next thing we knew, he was buying her an Edwardian rowhouse in Cabbagetown, a Toronto neighborhood known for its raffish old-world charm. She had the place to herself all week, writing in her nightgown and cooking only as the spirit moved her (how I envied that arrangement). Sydney would visit on weekends, freshly manicured and bearing gifts of silk lingerie. Fredelle was done with sagging granny panties.

He booked the first of many lavish overseas trips. My mother couldn't believe her good fortune. In 25 years of marriage to my father, she traveled nowhere but Winnipeg to see her mother, unless a magazine was footing the tab. Her suits came from Filene’s Basement, her no-name pumps from Red’s Shoe Barn. She had honed the art of self-denial with the same unbending rigor she brought to her prose. The basket millionaire had other plans for the woman he loved.

One time she led me down to the neglected basement sauna, beaming at the secret she couldn’t wait to share. The door opened on a pastel tumble of pillows—velvet, silk, Indian cotton—strewn across a futon she had draped and smoothed like a concubine preparing for the sultan. She clapped her hand over her mouth, as if she didn’t dare let on how she relished her new life as kept woman. My mother—guardian of grammar, queen of the Thanksgiving table, raconteur who declaimed every story the way it should have happened—was now the doyenne of her own sex room.

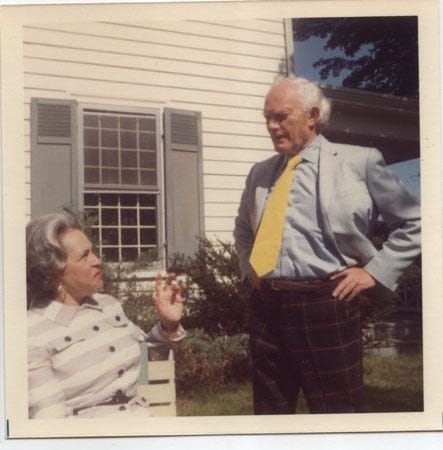

Sydney didn’t fit my image of the dashing lover. A wizened gnome 12 years older than my mother, he strode into her parties in the Rolls Royce of hearing aids—enormous black headphones tethered to a mic that picked up snippets of what you said. While he strained to hear, his smile became a grimace. He never missed a word my mother spoke, and in the pauses between her anecdotal flights he would hum tunelessly to himself. His ties came from Sulka on Fifth Avenue, his air of self-regard from the unbending assurance that anyone worth knowing could not help but want to know Sydney Bacon. I didn’t much like him but he made my mother happy as no one on earth ever had. His confidence enveloped them both, like a shell that by some miracle is home to two snails.

An unfamiliar softness came over my mother. She often spoke of Sydney’s wisdom, quoting him when I slipped into a funk. You are never out of options, he maintained. Pay attention, and they’ll come into view.

Love always puts a test to the lover. My mother never wrote about the test she faced with Sydney, early on. She wouldn't have wanted to embarrass living people, least of all herself. The dead are beyond embarrassment, and no one knew better than my mother that a story calls out to be told.

Virginia had been cleaning Sydney's condo once a week. Their deal included sex. Did he take her to bed before she washed the sheets, or after, so he could inhale her scent between visits? At the time I thought only of my mother's anguished fury. In her view and mine, love demanded fidelity. She told Sydney he would have to choose between her and the cleaning woman, whose name froze on her lips. He wept and pleaded for mercy: “I cannot give her up.” Did he not understand betrayal? The whole thing smacked of droit du seigneur.

So much for the Basket Millionaire, I thought. When Fredelle Maynard took a position, that was that. I’d forgotten the magic word: options.

Sydney flew my mother somewhere—Chicago, I think—to consult a friend of his, the poet and social worker Carl Rakosi. I detected power politics, two men ganging up on a woman undone, but Rakosi zeroed in on the crux of the matter. He asked my mother, "When you are with Sydney, do you feel loved?"

She did, absolutely and completely. My father had been faithful until, on the brink of retirement, he fell for a worshipful student on the campus where he’d been the lowest-paid man in his department. But desire did not come easily to him, except for art and poetry. Sydney desired my mother. Her size 14 figure, a source of shame all her life, was for him the font of joy. In his arms she ripened.

My mother and Sydney had their deal, as every couple does. It included the cleaning woman. Cavil if you like; it suited them. Fredelle never gave Virginia another thought. Her one small regret about the love of her life was that Sydney had ruled out marriage. Bitterly divorced, he had no truck with wedding vows. And besides, he counted on my mother to outlive him. She was younger, after all. Never felt the need to see a doctor, walked six miles at a stretch.

They’d been together 14 years when brain cancer came for my mother. A glioblastoma, bad as it gets. More time together would not be an option, yet they hadn’t run out of options. Sydney married my mother one June morning in a garden full of jubilant friends. The rabbi declared, as Sydney smashed a wine glass under the chuppa, “There never was a couple like this and there never will be again.”

Sometimes I walk my dog past the house on Metcalfe Street where my mother blossomed. Subsequent owners took down the rustic wooden fence and paved the front yard, but the same knocker hangs on the door. She and Sydney brought it back from somewhere, a female hand made of hammered metal, the fingers lightly brushing the wood as if on the point of a caress.

Have you ever made—or witnessed—a bargain made for love that worked in its mysterious fashion? Could it be that fidelity is overrated? And how about the dynamic between an adult child and a middle-aged parent on a sexual adventure? You’re a seasoned group and I can’t wait to see where you take this conversation.

She stayed with him, knowing she could not have him to herself. He married her, knowing he would lose her. As Golde sang in Fiddler On the Roof “If that’s not love, what is?”

Lovely story, Rona. After both of us divorced (me first, them my only sibling 10 years later) my brother and I talked about how we both found humility and acceptance of how couples found a way to be together that worked for them.