Little Store on the Prairie

I thought I knew my mother's story. Then old letters revealed a chapter with a Stephen King vibe.

My mother used to tell an old Jewish joke about a family gathered at the deathbed of the patriarch, a storekeeper. The punchline cracked her up: "Who's minding the store?" I never saw the humor but then I was not a storekeeper's daughter.

When I was nine months old, my mother took me by train and two propeller planes to Grandview, Manitoba to mind the O-Kay Store—the last of the general stores to carry her parents’ fading hopes. The only Jews wherever they went, they thought they’d seen every kind of hard luck: crooked suppliers, failed harvests, thieving staff, competitors with deeper pockets. Then my grandfather took sick. While Grandma kept vigil at Grandpa’s hospital bed in Winnipeg, someone would have to mind the store. My mother packed our bags. She promised my father we’d return as soon as Grandma gave the all-clear.

It was July, 1950—the Korean War just begun, moviegoers flocking to Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah. Men wore fedoras to the office, women shopped for groceries in girdles. When the crisis broke in Grandview, my mother was launching a career as a freelance writer. “Fredelle Maynard, PhD” she signed herself for the baby magazines (the editors never knew she’d earned her doctorate in English). At 28, she had accepted the loss of her dream, an academic post. Women scholars had a raw deal—especially married, Jewish women. But Plan B did not include minding the store with no end point on the calendar.

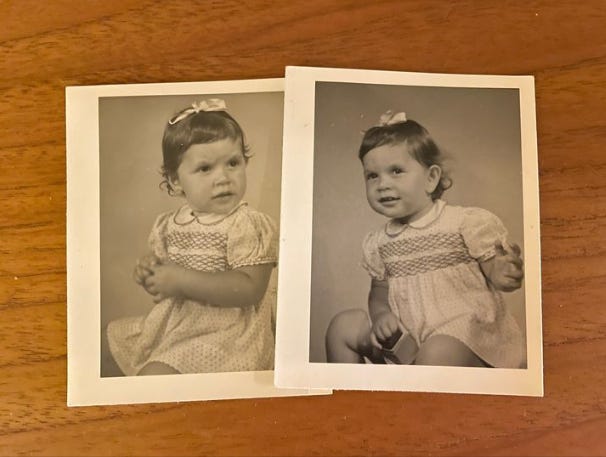

If you had to be marooned with a baby in a general store on the prairie, I was the baby for you. I had no interest in the snack potential of Comet or the meeting of a pudgy finger with an electric socket. Fredelle could plunk me in the toy department and there I’d sit, contemplating the amusements from my rocking chair. She never spoke of our sojourn in Grandview, and I was too young to remember. It might as well never have happened. But it did happen—the loss of her foothold in the world, the near-loss of her father, the drumbeat of worry for her young marriage to a dashing alcoholic. The loss of her very self.

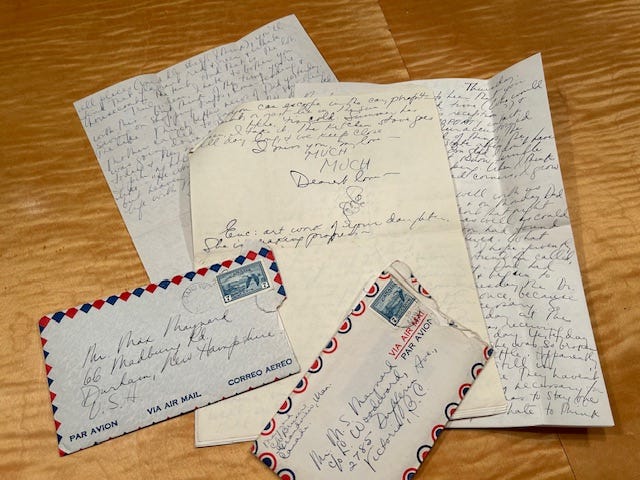

Some families used to keep leather-bound Bibles, every birth and death noted on the flyleaf. My family has the letters my mother wrote from her early days with me, her firstborn, until her death at 67, a span of 40 years. When I want to hear her voice, I turn to the voluminous carbon copies—each one typed, single spaced, pages long—that unfold like a picaresque novel starring her indomitable self. She could turn common blowhards into characters worthy of Dickens, a Tupperware party into a set piece that showcased her pluck and wit. “I’m a happy person,” she used to say. Letter after letter seemed to prove it.

The Grandview letters tell a different story. They’re like notes for novel inspired by The Shining. Never part of the Fredelle Maynard canon, they lived in a separate folder, open secrets I chose to ignore until my mother had been dead for more than 40 years. I’ve never been much of a hugger, and my reticence used to pain her. The Grandview letters make me want to hold young Fredelle in my arms. Sometimes a woman riven by distress needs an old woman’s unjudging eyes to steady her.

Fredelle went nowhere in Grandview, saw no one but the customers, a sour helper named Marie and the infant daughter who became the only witness to her mounting desolation. Her typewriter and books were at home in New Hampshire. She wrote at night, her pen racing to keep up with her onrushing worries. While I slept above the store, she hurried to the mailbox, hoping no one would choose that moment to break in.

“My darling. A manless life is a lonely life to be sure. I am feeling terribly uprooted and driftwoody. Rona is a cheerful little soul and very loveable in her own way, but she doesn’t quite serve the purpose. Our conversations proceed at a low level (da-da, pattycake, bye-bye)…. I will soon begin to talking to myself, for I can’t talk to Marie very long without skirting a thunderstorm.” My grandfather’s illness had kiboshed Marie’s vacation; she couldn’t forgive her employers.

Weeks passed with no good news from the hospital in Winnipeg. Fredelle had reason to fear she would never see her father again. And meanwhile she feared for our household in New Hampshire. My father had a passion for truth and beauty but couldn’t or wouldn’t get his head around the family budget. He’d just taken a trip to Vancouver when she wrote, “You’ll probably find a backlog of electricity and phone bills; be sure to pay them promptly. Also: The rent is due and also, I think, the next instalment of our automobile insurance. I’m assuming that we have money in the bank to pay all these things. Do let me know exactly what your trip cost, and what we have left in the checking account. I expect we are poor, poor.”

Seventy-four years on, I hear her thoughts: “An assistant professor should not be gallivanting to Vancouver. I am holding onto the family business; you were throwing money we don’t have to the winds.” But she would be a good wife and keep the peace. She knew well enough what would happen if she set him off. “Just see that you don’t go a-drowning your troubles in anything more than gingie, and don’t try to live on oatmeal and liverwurst sandwiches.” She never explicitly discussed my father’s drinking. How innocently she tucked the sidelong mention beside the oatmeal and liverwurst sandwiches.

My grandparents had fought her marriage to a Gentile (older and divorced, at that). They came around when I arrived. But my mother had come to doubt the wisdom of her choice—not that she dared admit the truth to her parents. The free spirit who entranced her with his talk of Cézanne and Blake had revealed his true self: an overgrown child in need of protection. Now her parents needed her. After breaking their hearts, she dared not let them down.

In early October, her hopes briefly flared for my grandfather’s health. She was making plans to head home when the bulletins from Winnipeg turned grim. Could my father please send our winter coats and mitts? And the locket and bracelet, a baby gift from someone, which would fetch five dollars we needed more than jewelry? My face had broken out in a rash; the local doctor was useless. My father had better send the ointment.

“I am, as you can imagine, utterly miserable. Sunday is always a drear day in any case, and tomorrow (Canadian Thanksgiving) the store is closed, so that means two days of being completely alone. When the store is open, there’s more work, of course, but at least there are signs of life, and people and things to occupy one’s mind with matter-of-fact affairs. There are all sorts of things I could profitably do, even without books, if I were alone and peace-of-mindy, but being alone in a state of constant tension unfits me for any sort of creative activity.

“I miss you. I love you. I want to come home. And O I do so want everything to be all right with Dad.”

When my father phoned Grandview, a wild extravagance then, she put him in his place. “My darling—I do dislike long distance calls. They accomplish nothing positive, and they leave such a vague and futile melancholy behind. And I particularly dislike receiving such calls in Grandview, with Marie at my back listening hard and the local operator probably taking notes for the girls.

“I’m sorry if you’ve been letterless and worried. I thought I’d been fairly good about writing. But it’s not easy to get a letter off when I’m in the store pretty steadily from 8:30 a.m. Of course I come in for necessary matters—Rona’s meals and naps and pant changes, and the incessant hand laundry—and even those take up so much time that I just don’t dare leave Marie to work up more grudges…. She’s in a constant burn, which makes my lot pretty cheerless….

“I know it’s hard for you to be alone; and I feel terribly anxious about it—but then I’m not here holidaying…. O it’s just unspeakably bleak, rattling around the house and store alone! I have lost 10 pounds since Dad has the operation….”

Ten pounds gone like that. All her life my mother struggled to lose weight. I wish I could ask her about this “hand laundry.” Did she wash my diapers in the sink? She mentions “fires.” Was there no central heating as cold settled on the prairie?

I turned one on October 20. Of my first year in the world, I had spent three months alone with my despondent mother. On October 22 my grandparents came home to dust and disorder. Snow blanketed the best wheat crop in years, a bad sign for business. My grandfather was in no shape to run a store; they would have to find a buyer. My mother made plans to head home on November 14, but first she needed one more package from New Hampshire:

“I tremble and lower my voice when I speak of parcels. But really truly this is the last request. Did my girdle ever come—the one I asked you to send for? If so, I wish you would send it on. It would not be complicated this time. Just paste a new label over the old one on the box, take it to the post office, and make out a declaration form (which they will give you) for ‘1 girdle, value $4.95, property of addressee.’ I would much, much appreciate it.”

That girdle. After all she had endured, her butt and belly shamed her.

Perhaps she thought I hadn’t seen her anguish. And yet, if a dog can sense trouble in the house, why not a human baby?

The next summer my mother took me back to Grandview—just a visit this time, not a mission of mercy. I seemed chipper enough on the first leg of the train trip, but broke down in sobs when I sensed that we had far to go. Unable to eat or sleep, I begged to go home. My mother wrote to my father of the “harrowing” journey, “It is a shock to see how terribly dependent she is on her LARES ET PENATES—Daddy and Christopher [the cat] and Rona’s housie.”

I am now almost twenty years older than my mother ever got to be. And I know without a doubt that she had my distress all wrong. I couldn’t bear to see her undone. When it comes to the fears that rend a family, children don’t miss a thing. It’s the grownups who fool themselves.

Okay, Amazement Seekers. Have family letters ever shown you a whole other side of your parents, maybe even your young self? Is there something you wish you could ask a parent? (I do wonder about those fires and diapers.) Don’t feel confined by my questions—as if I have to remind anyone. You people have a knack for starting conversations.

My mother has inspired some of my most popular posts. The gatekeepers missed out when they declined to give her a permanent post—as you’ll see “Shirley Jackson, My Mother and the Story That Rocked My World.” And midlife brought her a great romantic adventure, albeit with a catch. See “Love, Sex and the Cleaning Woman.”

If you’ve been enjoying my posts and are in the mood to be generous, your paid subscription would make my day. Honestly, though, you all delight me just by reading Amazement Seeker. That’s why it’s free to read and will remain so. Every time you share a post, leave a comment or simply click the heart, you’re helping these letters to the world find a few more readers.

Oh my. Yes. Thank you for this. I often wonder what my mother experienced in the moment, while married to my father. I know it was hard for her––an un-winnable trek in a dysfunctional marriage. So amazing to be able to look back and see some of your mom's struggle and her commitment to her loved ones. And the girdles, and the expectations, and all the things to juggle, while putting ones hope and desires and dreams to the side, to be there for family, often at the expense of their own peace and happiness.

Rona, this is such a beautiful/wrenching story. And the photos are lovely reminders of those years and a charming old store much like one I remember seeing in the early fifties in my home town. The old people who owned and ran the store, six days a week, had changed nothing since they went into business in 1901. It was a grocery/general store with lutefisk in barrels beside a display of logger’s tin-hats and hobnailed boots. Although my mother shopped up the street at the modern Safeway, my Norwegian grandmother would take me to what she called “the Finn’s store” where she could get “a nice piece of oilcloth” cut to the length she needed, balls of darning yarn and crochet thread, a pound of pink peppermints weighed into a little white bag, a chunk or two of the good lutefisk, a bottle of cod liver oil, hard-tack, and her cheese that looked, to little girl me, the same as her bar of Fels-Naptha soap. And, she bought the Aftenposten, a Norwegian newspaper.

Your story brought my own treasured memories to the forefront of my mind. Now in my seventies, I think of how my grandmother savored her trips to that store - a store that reminded her of the homeland she left at age nineteen and never saw again.

Thank you for pointing me down this trail, Rona. I must write more of these memories of Grandma down before I forget them.