Portrait of the Artist as a Woman on Fire

Marisol, who soared to fame in the 50s, broke the rules for her gender and defied categories. Her work still blazes with urgency.

The icons of my girlhood showed me three roles a famous woman could play. The Wife: Jackie Kennedy, who redecorated the White House and gave the grand tour on TV, the picture of elegance in pearls and red bouclé. The Temptress: violet-eyed Liz Taylor, as famous for stealing Richard Burton from his wife as for making a million dollars to star in Cleopatra. The Face: Jean Shrimpton, her saucy perfection gracing every newsstand.

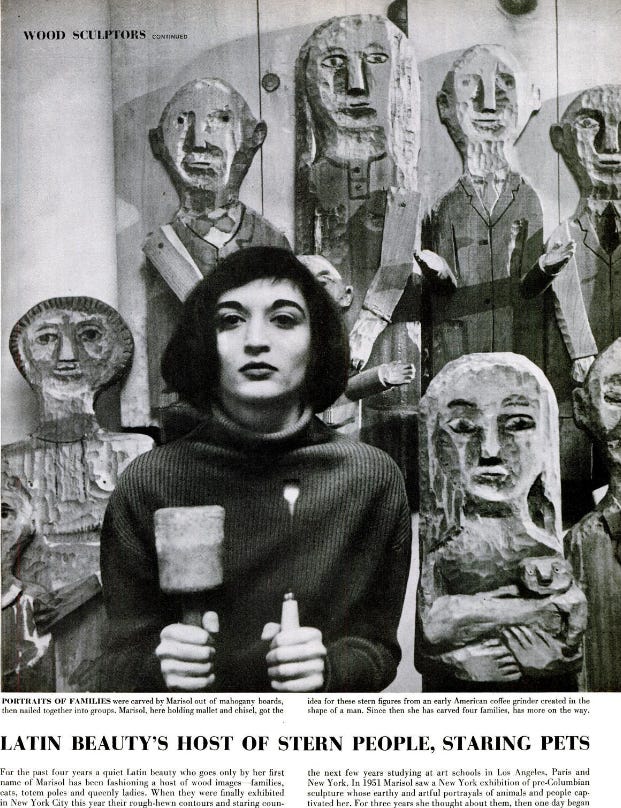

Then along came Marisol—“the first girl artist with glamor,” according to her friend Andy Warhol. Born in Paris, raised in Venezuela, steeped in New York’s bohemian art scene, she walked a rebel’s path to fame. She had the chutzpah to jettison her father’s name (Escobar) and the independence—mystifying at the time—to veto marriage and children. It’s not as if she couldn’t attract a man. LIFE, my favorite of the magazines that cascaded through our mail slot, called her a “Latin beauty.” Time marveled at the “black-haired, wide-eyed, unmarried woman of 33 who speaks in monosyllabic whispers so faint that by comparison Jackie Kennedy would sound like a cheerleader.”

The Time piece appeared in 1963, when the median age of first marriage for an American woman wasn’t much over 20. Yet here was Marisol, going it alone well past the dread threshold of spinsterhood. I must have read the story, and it surely puzzled me. Almost 14, I’d heard my mother say all my life, “When you marry and have children of your own…” Yet I also saw her chafe at the weight of domestic expectation.

It was in 1963 that Betty Friedan exposed “the problem with no name” in The Feminine Mystique. Briefly emboldened by Friedan’s manifesto, my mother stormed out of the house one night, leaving dinner half-finished in the kitchen. We took her for granted, she said. She’d been cooking all afternoon—a new recipe that demanded much browning and chopping, plus the nightly fried chicken wings because my sister would eat nothing else. And for what? A family that preferred to watch a Western instead of exclaiming at her culinary prowess. Far from cheering her on, I resented what I took to be her selfishness. I wanted a proper dinner, not whatever my ham-handed father could assemble. My mother never turned her back on dinner again.

Marisol knew the score. The way to escape the chains of domesticity was never to accept them in the first place. The woman who whispered to the press was an uncompromising artist who proclaimed hard truths in the wooden sculptures that made her name. With ferocity and wit, she challenged the assumptions that kept women down. She died in 2016, just shy of her eighty-sixth birthday. Yet as a vice-presidential candidate sneers at “childless cat ladies” and regressive abortion laws threaten both the lives and the fertility of pregnant women, her work still blazes with urgency.

Last week I visited the retrospective now on view at the stunningly expanded Buffalo AKG, the first American museum to purchase a Marisol and home to the world’s largest collection of her work. I won’t attempt to capture the sweep of her vigorous creative challenge to the status quo (this feminist was also an environmentalist). Join me on a mini-tour of some highlights.

“The Family” sends up the American ideal with a frozen paterfamilias and a balloon-breasted mother who literally has no clue where she’s going, thanks to the hat obscuring her view. Whatever Vogue decrees, she’ll wear. The kids are grotesques: two clownish toddlers and a stolid, three-legged girl who appears to be in training as a future homemaker and leader of the Ladies’ Guild. Marisol liked to encase her characters in boxes that express their confinement by a culture intolerant of difference. Remember Malvina Reynolds’ hit song “Little Boxes,” about look-alike suburban tract houses “all made of ticky-tacky?” First recorded by Pete Seeger, it charted in 1963.

What Marisol deplored, Time magazine wanted to save. In 1970 the sculpture appeared on its cover, alongside the ominous headline “The American Family: Help!” Teenage runaways, long-haired dreamers in communes, a declining birth rate…surely the end was nigh. The writer tossed all manner of roughly chopped theories into the soup of feigned objectivity, but “Women’s Lib,” then acceptable journalistic parlance, kept floating to the top. Opined a sociologist I won’t name, “When a woman is working, she tends to have a new perception of herself. I see this most egregiously [my italics] in those women who go to liberal arts colleges, because there the professor takes them seriously, and this gives them big ideas.”

Marisol inserted her own image into work after work—plaster casts of her delicate hands, photos or casts of the face. Traditional self-portraits place the artist front and center, before an easel or lost in thought. Marisol placed herself on the fringes of a hostile society, the unflinching witness to oppression. In a self-portrait from the early 60s, her penetrating gaze emerges from what look to be the stocks used for punishment in centuries past. She shares the instrument of torture with someone yawning or screaming, someone blindfolded by a low-slung hat and various faces evoking other cultures. When a critic dismissed her as a folk artist, she wrote in an unpublished document, “If you call my work folk art, it is only because you are prejudiced against my South American background. Folk you.”

Marisol’s art often bristles with defiance—as in “Baby Girl,” the monstrous, beribboned infant who dwarfs a doll with the artist’s face. No two ways about it: The prospect of motherhood appalled her. Yet she had a profound empathy for children. In her sculpture of the John F. Kennedy’s funeral, the president’s grief-stricken little boy towers over a toy-sized cortège, his face riven with grief, shock and fear of the looming fatherless void. Marisol’s rendering compounds the poignancy of the photo that moved a nation; I can almost feel her hand chiseling young John Jr.’s cheekbone, like a caress. They shared a bond, those two. Marisol was 11 when she lost her mother to suicide. In her anguish, she stopped speaking.

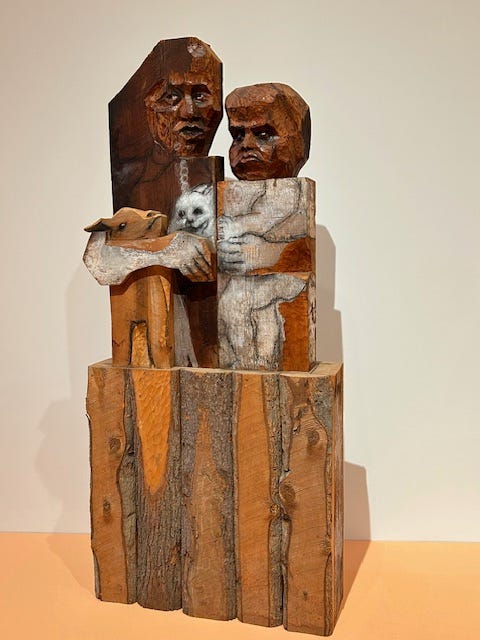

Commentators used to wonder what to make of Marisol. Some called her a pop artist because she satirized mass culture (TV dinners, Mattel’s Midge doll). Yet her work has an intimacy you don’t see in Andy Warhol’s or Roy Lichtenstein’s. White men defined pop with irony and hard edges. Marisol, a Latin American woman, drew on a well of feeling, from the righteous anger of her feminism to her compassion for the dispossessed. Look at the faces in “Woman and Child with Two Lambs,” based on a Depression-era photo of Dene people exiled from their land by the U.S. government. The child looks ready to explode with rage; the mother, struggling for calm, seems to scan the horizon for signs of hope. I think of the Madonna and the lamb of god, but if this pair believed in heaven, I suspect it’s the home they have lost.

In her heyday Marisol was everywhere. Gloria Steinem wrote about her for Glamour. Warhol filmed her looking into the camera—along with Salvador Dali, Lou Reed, Bob Dylan, Yoko Ono and hundreds of other famous friends. Yet celebrity could not pierce the conundrum of her, this resolutely original artist who defied categories and guarded her privacy. If she ever drank and fought and competed with a larger-than-life artist lover, like Lee Krasner with Jackson Pollock and Elaine de Kooning with her husband Willem, she kept it to herself.

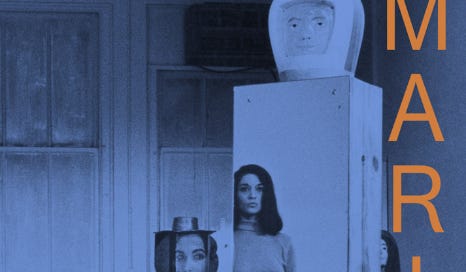

The youthful Marisol would still be the coolest person at any art opening she chose to grace. On the cover of the book on the new retrospective, she wears her baggy turtleneck and tights as if they came from the avant-garde boutique of the hour. Women would wonder who cuts her hair while men wait for their moment to capture her attention. That would take some doing. “Let’s see the best you’ve got,” she seems to be saying. “I dare you.”

Marisol: a Retrospective is worth a trip to Buffalo, where it’s on until January 6 before moving to the Dallas Museum of Art, February 23 to July 6.

And now let the conversation begin. Who’ll jump in first with a comment on girlhood icons, saying no to motherhood, what makes art of the past relevant today…any thought that appeals? If you’ve stopped here before, you know I’ll reply.

Art has been a wellspring for me since childhood. Head over here for my take on Bonnard, the joyful melancholic, and here to explore what all creators can learn from a small but powerful Rembrandt. My father was an artist whose dreams of fame went unfulfilled; here’s the story.

Although my posts are free to read and will remain so, I’d be overjoyed if you’d consider a paid subscription. Either way, I’m honored to have you in my story circle. You could be calling mom or taking care of the laundry, but here you are with me. I don’t take it lightly. Next Sunday you’ll find me right here with a fresh pot of virtual coffee.

Thanks Rona for this terrific introduction to Marisol, an artist I didn't know. Her work has both depth and wit. And I loved this quote you cited: "If you call my work folk art, it is only because you are prejudiced against my South American background. Folk you.”

I feel like I knew about Marisol but forgot her. Thanks for bringing her back to my forefront! I was fortunate to be surrounded by all types of art growing up and have parents who bought and spoke about art even though we didn’t have much money.