How to Keep a Friend

The usual rules don't always apply between artists. Abuse might seem a fair price to pay for inspiration.

Forty-odd years ago, with a question on my mind and time to kill while passing through Vancouver, I went to see my father’s old friend Jack Shadbolt. His wife greeted me looking troubled and proceeded to explain herself. My father had repeatedly wounded her husband. To Doris Shadbolt, Max Maynard was poison.

Jack proposed to take me on a drive. For an artist of some renown, he drove a car of startling decrepitude, a station wagon that could still haul his paintings around but did not pass muster with his wife. She called from the doorway, “You know, Jack, you ought to get the brakes checked.”

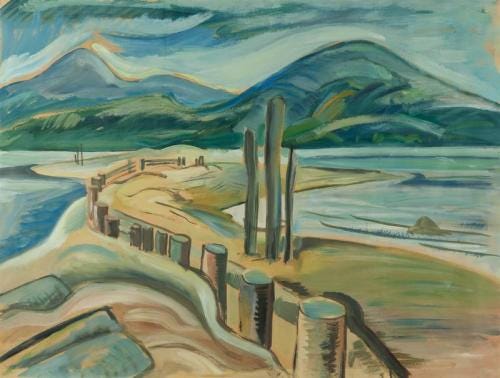

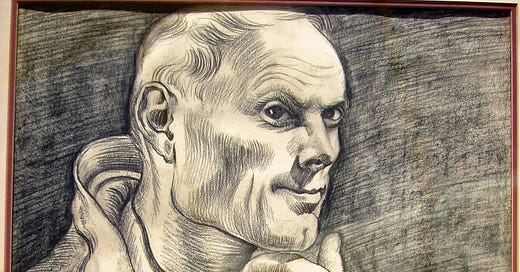

Jack was the friend of my father’s bohemian youth. He talked of that golden time the way Adam must have talked about Eden. With sketchbooks under their arms, he and Jack roamed forest and coast around Victoria, B.C., a stomping ground so beautiful it shamed every other place he’d known. Two modernist painters out to shake up their prim little city, they tagged along after the still-unknown Emily Carr, until she tired of their attentions. Jack looked up to my father. Five years older, square-jawed and flashing-eyed, Max Maynard seemed the quintessential firebrand. He talked like one, too, in complete paragraphs that unfurled like an oration or a prayer. On their rambles he quoted Wordsworth. Splendor in the grass, glory in the flower. They would capture it and make their names.

Jack stayed true to his calling. He won awards and honorary degrees, represented Canada at the Venice Biennale. My father lost his focus. He ended up teaching English at the University of New Hampshire, where he spent his entire career as the lowest-paid man in the department (there were no women). With only a bachelor’s degree, he was lucky to have that job.

He often boasted of his friend the famous artist, but envy seeped from him. Jack lived the life that should have been his, painting in a mountainside studio in suburban Vancouver while Max Maynard painted after hours, in the attic. Jack exhibited internationally; Max’s only gallery was our house. I’d never met Jack or seen any of his work except the modest water color he’d given his first mentor. “A poor thing,” said my father, who hung it in a corner.

When my father made a sale, it was to a colleague, for a song. To them Max Maynard was a hobbyist, a maker of affordable décor to hang above the mantel. Some of them may have pitied him, shivering the winter nights away in that unheated attic. He would rage, “I could have been the most famous painter in Canada!” He didn’t have to add, “if not for my wife and children;” we all got the point. Jack and Doris, a curator and art writer with quite a reputation of her own, had no children to put through college. They didn’t have to pay for ballet lessons, Christmas toys and Stride-Rites. They lived in a temple to Art.

I rejected my father’s take on his fortunes. If he didn’t want a family, why on earth did he have one? Grownups lorded it over kids for their presumed equanimity and judgement, yet this grownup threw tantrums worthy of a two-year-old. He would berate Jack on the phone: “You’re a charlatan! A second-rater!” Long-distance calls were a luxury then, reserved for three situations: Grandma needed an audience in Winnipeg; one of us girls needed to check in from somewhere (we had five minutes); Jack Shadbolt needed to be put in his place.

I couldn’t replace Max Maynard with my notion of a good father (Ward Cleaver with a turtleneck instead of a tie). When it came to good friends, Jack surely had options. Yet he not only stayed on the line for my father, he came back for the next verbal beating. If any friend of mine called me names, I’d have cut that person dead.

According to my father’s moral code, Art with a capital A justified a certain recklessness with social norms. Other people might resent the final exams never marked, the fights picked at faculty cocktail parties, the scenes at the teak dinner table. But someone would always would cover for him (as my mother put it, “He’s a brilliant, original man”). No one mentioned the other A-word: alcoholic. Besides, who looks to Artists for propriety and selflessness? Gauguin left his family. Dickens too. Picasso, Hemingway, Kerouac, Dylan Thomas… world-class hellions all. Either Jack Shadbolt was a chump, or he followed a different code.

After I left home to find my own place in the world, I forgot about artists and their code. I worked in the magazine business, where you either pulled your weight or lost your job. I cut 100 lines on deadline, stood up to writers who accused me of destroying their voice. Jack Shadbolt fell out of my consciousness.

Meanwhile my father was returning to his creative roots. Retired from teaching and sent packing by my mother, he sought refuge in the one place he’d ever felt at home—Victoria. He rekindled ties with family and friends, not least Jack Shadbolt. He took up painting full-time and began to show his work. Arthritis forced him to substitute a palette knife for a brush, yet he flowered in old age. When the Burnaby Art Gallery mounted a one-man show, Jack wrote an appreciation for the program.

“His landscapes are all the same landscape,… a melancholic yet inwardly joyous cadence that never wavers.”

How he must have labored to express precisely what he meant, knowing his lifelong mentor and rival would scrutinize every word. He didn’t pander to my father’s vanity, even called Max Maynard “an unrealized artist” who “never produced the body of work his sketches hint at.” My father must have known this was the truth. But he’d have treasured Jack’s attention to his vision. “His landscapes are all the same landscape, …a melancholic yet inwardly joyous cadence that never wavers. They have a tidal rhythm….”

You think you’ll hold onto every detail of the conversations that change you, down to the angle of the light. But you don’t always know, in the moment, that you are being changed. The particulars fall through a hole in your pocket. Forty years later (or is it forty-two?), you try to piece the scene together from the one thing you know for sure—how you felt at the time.

The old station wagon lumbers up the mountain. Jack keeps his eyes on the twisting road. Somewhere around 70, he has color in his cheeks and fills his shirt. A slight paunch makes him look reassuringly substantial. My father has become a wraith—his throat a deep hollow, his nose a beak. He doesn’t eat much but still drinks, although he’s trying to work the Twelve Steps. I hope life number nine has begun. My father makes me tired.

I watch the city fall away and the sky open up. An unfamiliar lightness comes upon me. I don’t have to think about my question. It floats from my lips. “Why is my father still your friend, after all the terrible things he’s said?”

Jack answers without hesitation. He was still in his teens when he met Max Maynard. A boy reaching for the purpose that took form on their adventures. They’ve had some 50 years together. You don’t throw that away because your friend is having a bad night. And while Max can be cruel, he has a keen eye for the gap between the painting on the canvas and the one in the mind of the painter. An artist needs a friend who understands the quest—the striving, the falling short, the starting over.

I thought friendship required an equal exchange of loyalty and devotion.

The road brings us to the foot of a chair lift, but rising higher isn’t part of Jack’s plan. I take in the peaks, the clouds, the great, undulating sweep of the landscape my father loves. He can’t speak of any place in coastal B.C. without exclaiming at its beauty. My mother used to roll her eyes: Here he goes again. What’s wrong with New Hampshire? But yes, my father had a point. New Hampshire’s beauty is a string quartet, B.C.’s a symphony. Maybe that’s why Jack brought me here, to feel the vibrations.

We’re heading down the mountain when the car picks up speed. It flies around a curve as if making sport of the driver. Jack steers like mad. Doris was right, he tells me with a smile. The brakes just failed.

I have a primal fear of car accidents. It goes back to earliest childhood, when my father would grip the wheel to wrest control back from alcohol, that word never spoken in our house. At three or four, I dreamed he vanished from the driver’s seat, leaving only his fedora hanging in the air as our humpbacked sedan hurtled toward oblivion. Descending a mountain without brakes is my idea of horror. Yet Jack seems more amused than alarmed. His hands rest lightly on the wheel. Good God, is he chuckling?

When my father died, aged 78 years and 11 months, Jack gave a eulogy. I can still see him at the podium, miming his old friend’s exuberant freestyle. My father had been a fine swimmer; in his art Jack recognized the rhythm of his stroke. After the service, Jack followed as the minister led my sister and me into the little room where our father lay in his coffin, a husk inside a glen-check jacket with a red rose in the lapel. We bowed our heads as a door opened in the wall and the coffin slid into the crematorium.

I was coming down with the cold of my life, the swelling in my sinuses a wave of grief—not for my father but for the man he couldn’t be. A man with the steadiness of Jack Shadbolt. I let myself believe he was there to support Joyce and me. At 33, I hadn’t yet lost any friends. I couldn’t fathom why anyone mistreated by a friend would feel the need to witness that friend’s body given to the flames. I thought friendship required an equal exchange of loyalty and devotion.

How simple it had been all along, this bond of theirs. By urging Jack forward when it mattered most, my father gave his friend to himself. The gift withstood everything he took in the years of his bitterness. I saw it that day on the mountain.

Jack trusted himself to get us down to safety, I trusted he was right. Wonder of wonders, the station wagon came to a stop. The friend of a lifetime had gentled the beast. I would almost have flown down that road again to sit with Jack in his old beater, giddy with amazement at the ride.

What have you learned about being a friend? How much grief would you take from a friend with one special gift? Where do you draw the line? Or take this conversation in another direction. There’s so much to explore when it comes to art and friendship.

Speaking of friendship, longtime reader and art lover Lynn B. Sealey just became the first founding member of Amazement Seeker. Thank you, Lynn, for your encouragement.

I think between these two it all came down to their natures. Jack was naturally generous and inclined to be forgiving. My father was defensive and insecure. And an alcoholic. That compounded everything else

Rona, this is stunning. Honest, generous, nuanced, brilliant. It’s so easy to see one’s parents in a harsh light, to paint them in broad strokes with a knife. You’ve shown us that genuine friendship can survive and flourish for reasons we may not understand, but can honor and respect. Brava.