A Melancholic's Guide to Happiness

Some people have a gift for happiness. The rest of us have to create it, one mindful moment at a time.

My dog and I were circling the park when happiness wafted through me like bubbles blown from a wand. It was a morning like any other that week—the daffodils past and the tulips not yet open, the sky more gray than blue. Arthritis was having its way with my foot. Chaos and cruelty filled the news. A firm voice within me told dread, “Get lost. I have loveliness to find.”

My first bee of the season alighted on a flower, close enough to touch. A robin flitted past with a twig in its beak. At my feet lay swirls of latte-colored fur left by someone grooming a dog—a big and shaggy one, by the looks of things. Soon the fur would be gone to warm nests for lucky birds. I practically floated home, the leash swaying in time with my steps.

“There’s just no accounting for happiness,” wrote Jane Kenyon in a poem I love, “or the way it turns up like a prodigal/ who comes back to the dust at your feet/ having squandered a fortune far away.”

Only a poet on intimate terms with depression—“the mutilator of souls,” she called it elsewhere—could have written this ode to quicksilver visits from joy. I’ve had my own struggle with depression. Kenyon whispers in my ear like an understanding friend. Yet I’m not entirely sure there’s no accounting for happiness. I noticed the bee, the robin and the fur because I looked with intention at the beauty around me and not at the gloom inside my head. Days before, I had walked the same route heavy-hearted. William James said when psychology was new, “The greatest weapon against stress is our ability to choose one thought over another.”

It sounds so easy to create my own mood. If only.

I’m a lifelong melancholic. My homing instinct for what could and should be better served me well at the helm of a magazine: rewrite, reshoot, rethink. Personally speaking, it’s my ticket to the Weltschmerz Express. At nine or so, I lamented, “I’m not happy,” to which my Yiddish-speaking grandmother retorted with a crack of her wooden spoon against the pot, “Happy, schmappy, abi gezunt” (as long as you’re healthy). At 20, trying out for a campus production of The Seagull, I was typecast as the sad sack Masha; “I am in mourning for my life. I am unhappy.” By this time, happiness didn’t interest me. Yearning did, that shining possibility just out of reach. Was “The Dead” a happy short story? Joni Mitchell’s “Blue” a happy song? If happiness had a secret, then surely it was low expectations for yourself and all the world. Happy, schmappy.

When I finally started therapy at 36, all I asked was freedom from despair. Lo and behold, I crossed over from a mental desert to a garden where every leaf and petal seemed to glisten. My last act of the day was giving silent thanks for some gift of a moment—a Mother’s Day card my son made himself, holding hands with my husband when he said, as if he couldn’t believe our good fortune, “You know, dear, you’re a lot more fun to be around these days.” So this was happiness. Who knew it could be mine?

Soon enough, I hit some typical midlife downers: a slump in my career, doldrums in my marriage, my mother’s final illness. But circumstances weren’t entirely to blame for the increasing dullness of my mood. After my recovery from depression, I got cocky. I stopped looking for moments to honor at bedtime. Mood creation reminds me of yoga: if you don’t keep it up, your body reverts to stiffness.

My natural state is not an illness. It’s been close to 40 years since I last thought of ending my life. But I tend to neglect those mental downward dogs. Haven’t I already done enough? For a melancholic, there is no such thing. Not if you want to know happiness.

Some people have a gift for making music, writing novels or running marathons. Nature blessed my friend James with a gift for happiness. He found beauty everywhere, which made him a hair-raising driver. Amid traffic on a busy highway, he’d exclaim, “Look at that bird!” while the rest of us flinched and his wife murmured with a sigh, “James, watch the road.” He had a child’s sense of wonder, and it must have endeared him to the kids he treated as a pediatric neurologist. I’m told he would walk the ward with children hanging from each hand. Many of his patients had incurable diseases that would take them down one faculty at a time. When I asked how he bore the anguish of it all, he told me his work nourished him. “I get to walk with families until the end. They know they can count on me. That’s their good outcome.”

James turned toward hope like a geranium toward the sun. For a melancholic like me, hope takes effort and commitment.

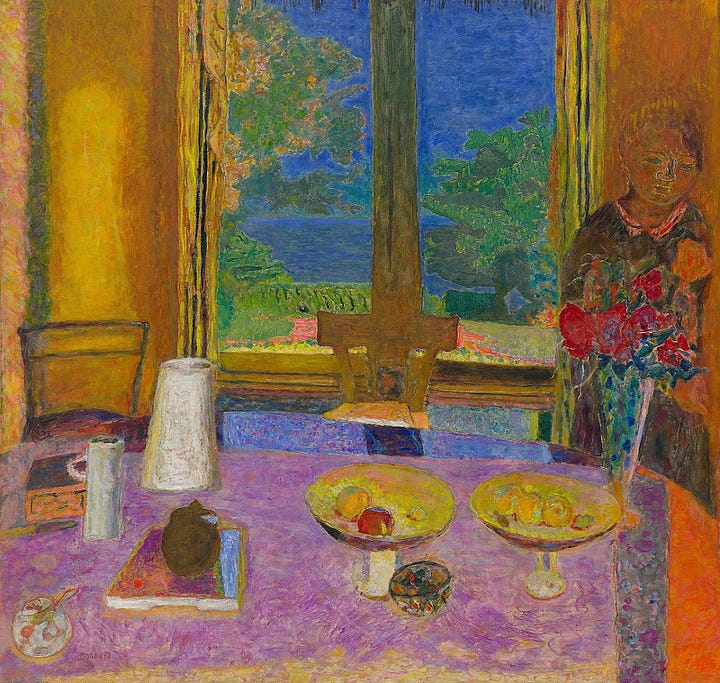

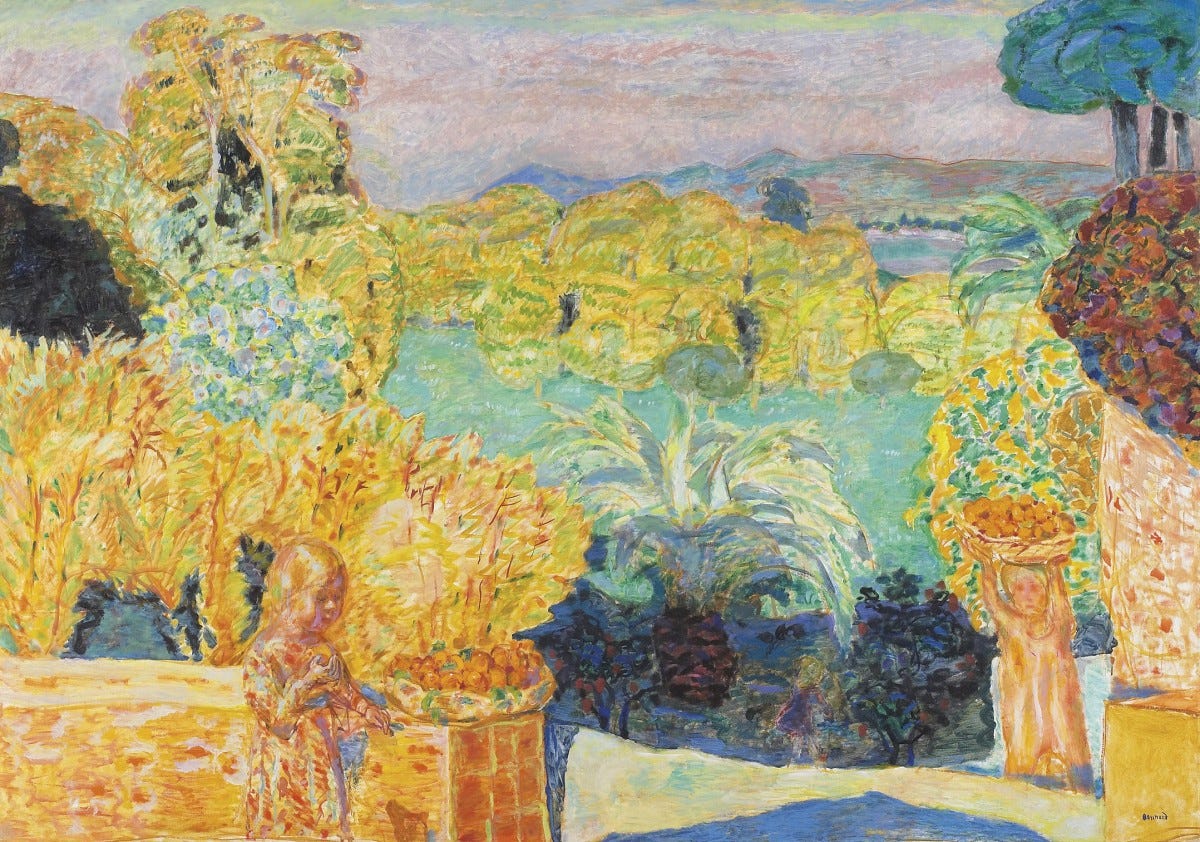

Pierre Bonnard, whose paintings recently entranced me at the Phillips Collection, was a fellow melancholic, not that I’d have guessed from my first sight of his lush palette and dancing swirls of paint. Feasting my eyes was not enough; I could have eaten up the exuberance. “So much joy!” I marveled to my husband.

“I don’t know about joy,” he said. “The people in these paintings don’t look very joyful to me.”

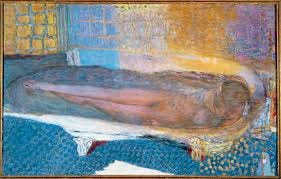

Bonnard, it turns out, is like Mozart on canvas. What seduces you is the rapture. What gives the rapture heft is the melancholy streak. The people in Bonnard’s paintings—notably Marthe, his nearly lifelong muse and partner—are often incidental to the animating vision, falling off the bottom of a picture or cut in half by a close crop of the scene. Marthe appears lost in thought, her features a blur. Faces didn’t interest Bonnard. He filled his canvases with all he asked of Eden—gardens, fruits, sunlight, cats and dogs—then dropped the people in to meld with it all. See the golden landscape at the top of this page? At first glance I missed the golden children.

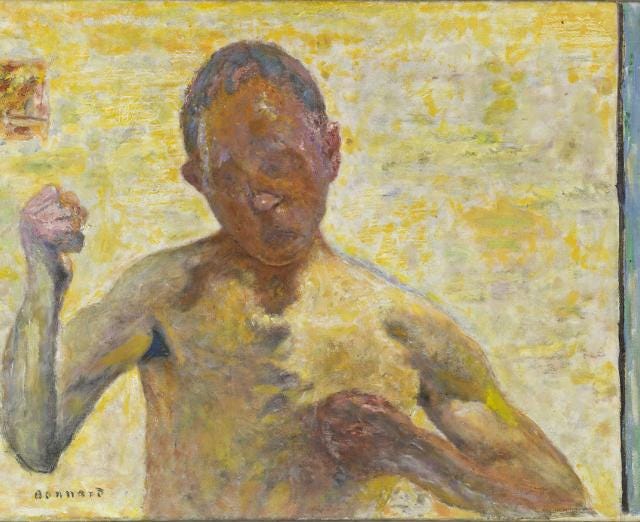

His self-portraits vacillate between loneliness and anxiety. In “The Boxer,” shown below, he seems to be pummeling his own sunken chest. And he had much to wish away in himself. Marthe waited many years for Bonnard to break up with another lover and make her his wife. When he finally did, the other woman killed herself. How could her death not haunt him?

“Joy and woe are woven fine,” said William Blake. Bonnard hinted at woe into every phase of his art. He was a master of post-coital sadness. But two months after I left the Phillips, his joy sings in me.

Happiness is not a steady state. Unless nature blessed you with a sunny temperament, you create it one moment at a time. Something may well stand in the way—if not a melancholy nature, then a stroke of ill fortune. You hold fast to what lifts you. Like my friend James, diagnosed in his 60s with a dire neurological disease. It took his career and then his life, one faculty at a time. I can’t begin to imagine what he and his family suffered. Yet in my memories of his illness, he’s always smiling.

On one of our visits to James and his wife in Philadelphia, we arrived to find him at the kitchen island studying Russian, intent on reading Tolstoy in his own language. We’d planned an outing to the Barnes Collection, a museum close to our friend’s heart. That bitter day, he made it to the door on a walker, step by halting step. The icy path seemed a dangerous place for a man in his condition, but James had paintings to share with us. He slurred his words, and I had to lean close to follow. At every stop on his tour, the point was love—for the paintings, for us, for being together one more time.

I wish I could have shown James the Bonnard exhibition. He’d have savored it. But I doubt any painting by Bonnard could have edged out his beloved Matisse that sustained him in his illness—a monumentally rhapsodic picture that once hung in Gertrude Stein’s salon. It’s his painting now. He’s in every flourish, holding fast to happiness.

I dedicate this post to James Wark—husband, father, physician, friend.

Warmest thanks to my newest paid subscribers: Betsy McMillan, Laurie Drucker, Bob Hoebeke, Pamela Martin and Ruth Pennebaker. I’m grateful to every single reader who joins me here instead of playing Wordle or cutting through your email queue. By showing up, you affirm my faith in the connective power of stories. Anyone who chooses to pay is giving me a double rainbow.

Know anyone who’d enjoy this post? Share to your heart’s content.

And now for the fun part: your comments. What makes you happy? Do you have to look for joy, or does it just fall upon you out of the blue? Any melancholics in the house? I’d love your perspective on the art of mood management.

Friends, it seems a few of you have drawn the conclusion that I continue to struggle with depression. I've done a bit of rewriting to clarify that melancholy is not an illness. I consider myself a healthy person who'd be wise to keep up good mental habits in order to experience happiness.

Another relatable piece, Rona. I'm not sure I aspire to "happiness" as much as I seek to feel grateful and at peace. With that lens, I'm open to appreciating the beauty of the world around me. It's been a life's work to reach those states. Physical and mental downward dogs help :) As does cultivating an ability to choose my thoughts and reactions.