Jewish Christmas

Santa left no gifts for Jewish children like my mother. Then one night he called her name. A classic memoir of love and difference by Fredelle Bruser Maynard

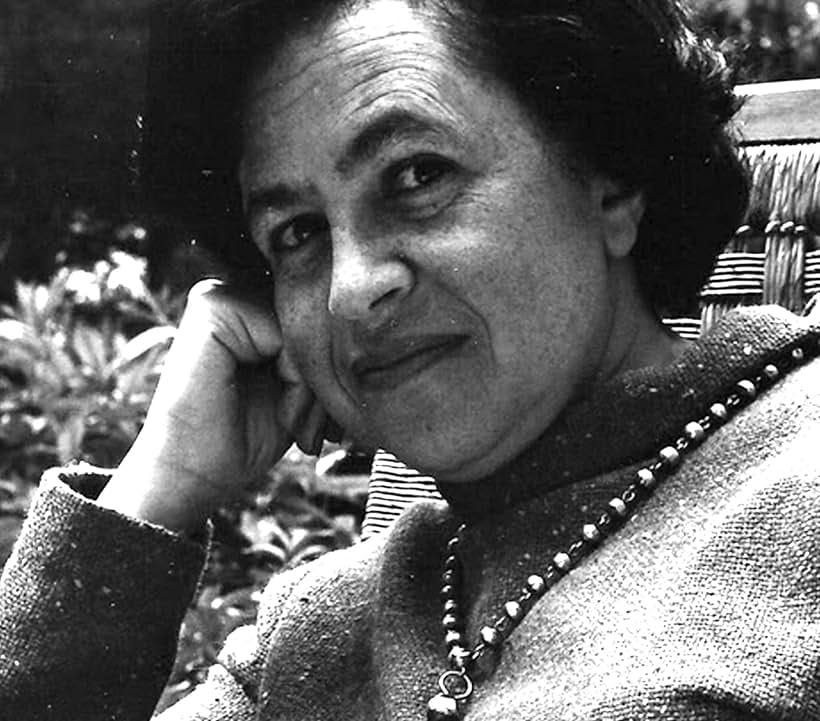

Every story I tell owes a lot to my mother, Fredelle Bruser Maynard—author, literary scholar, champion of the singular life as a portal to universal truth. She taught me to write as if I had to purchase every word, to listen for the music of language and above all to keep readers reading. Today you’re in a treat: her most beloved story, “Jewish Christmas,” from her first memoir Raisins and Almonds, a Canadian classic published in 1972, the year she turned 50. It’s been out of print for years; used copies turn up online.

I must have been in my early teens, my sister Joyce no more than 10, when our mother read the family her first draft of the story. No Maynard was too young for a place on her critique team. Fredelle was in her early 40s then, a successful magazine writer finding her voice as a memoirist. Typing the entire story for you, I touched her writer’s mind with my fingers. It seemed we were peers in conversation and that she, who died in 1989, had only slipped into the kitchen to brew another pot of mint tea. If you listen to the audio, you’ll hear my voice catch at the end.

Christmas, when I was young, was the season of bitterness. Lights beckoned and tinsel shone, store windows glowed with mysterious promise, but I knew the brilliance was not for me. Being Jewish, I had long grown accustomed to isolation and difference. Difference was in my bones and blood, and in the pattern of my separate life. My parents were conspicuously unlike other children’s parents in our predominantly Norwegian community. Where my schoolmates were surrounded by blond giants appropriate to a village called Birch Hills, my family suggested still the Russian plains from which they had emigrated years before.

My handsome father was a big man, but big without any suggestion of physical strength or agility; one could not imagine him at the wheel of a tractor. In a town that was all wheat and cattle, he seemed the one man wholly devoted to urban pursuits: he operated a general store. Instead of the native costume—overalls and mackinaws—he wore city suits and pearl-gray spats. In winter he was splendid in a plushy chinchilla coat with velvet collar, his black curly hair an extension of the high Astrakhan hat which he had brought from the Ukraine. I was proud of his good looks, and yet uneasy about their distinctly oriental flavor.

My mother’s difference was of another sort. Her beauty was not so much foreign as timeless. My friends had slender young Scandinavian mothers, light of foot and blue of eye; my mother was short and heavyset, but with a face of classic proportions. Years later I found her in the portraits of Ingres and Corot—face a delicate oval, brown velvet eyes, brown silk hair, centrally parted and drawn back in a lustrous coil—but in those days I saw only that she too was different.

As for my grandparents, they were utterly unlike the benevolent, apple-cheeked characters who presided over happy families in my favorite stories. (Evidently all those happy families were gentile.) My grandmother had no fringed shawl, no steel-rimmed glasses. (She read, if at all, with the help of a magnifying glass from Woolworth’s.) Ignorant, apparently, of her natural role as gentle occupant of the rocking chair, she was ignorant too of the world outside her apartment in remote Winnipeg. She had brought Odessa with her, and—on my rare visits—she smiled lovingly, uncomprehendingly, across an ocean of time and space. Even more unreal was my grandfather, a black cap and a long beard bent over the Talmud. I felt for him a kind of amused tenderness, but I was glad that my schoolmates could not see him.

At home we spoke another language—Yiddish or Russian—and ate rich foods whose spicy odors bore no resemblance to the neighbor’s cooking. We did not go to church or belong to clubs or, it seemed, take any meaningful part in the life of the town. Our social roots went, not down into the foreign soil on which fate had deposited us, but outwards, in delicate, sensitive connections, to other Jewish families in other lonely prairie towns. Sundays, they congregated around our table, these strangers who were brothers; I saw that they too ate knishes and spoke with faintly foreign voices, but I could not feel for them or for their silent swarthy children the kinship I knew I owed to all those who had been, like us, both chosen and abandoned.

All year I walked in the shadow of difference; but at Christmas above all, I tasted it sour on my tongue. There was no room at the tree. “You have Hanukkah,” my father reminded me. “That is our holiday.” I knew the story, of course—how, over two thousand years ago, my people had triumphed over the enemies of their faith, and how a single jar of holy oil had miraculously burned eight days and nights in the temple of the Lord. I thought of my father lighting each night another candle in the menorah, my mother and I beside him as he recited the ancient prayer: “Blessed art Thou, O Lord our God, ruler of the universe, who has sanctified us by thy commandments and commanded us to kindle the light of Hanukkah.”

Yes, we had our miracle too. But how could it stand against the glamor of Christmas? What was gelt, the traditional gift coins, to a sled packed with surprises? What was Judas Maccabaeus the liberator compared with the Christ child in the manger?

To my sense of exclusion was added a sense of shame. “You killed Christ!” said the boys on the playground. “You killed him!” I knew none of the facts behind this awful accusation, but I was afraid to ask. I was even afraid to raise my voice in the chorus of “Come All Ye Faithful” lest I be struck down for my unfaithfulness by my own God, the wrathful Jehovah. With all the passion of my child’s heart I longed for a younger, more compassionate deity with flowing robe and silken hair. Reluctant conscript to a doomed army, I longed to change sides. I longed for Christmas.

Although my father was in all things else the soul of indulgence, in this one matter he stood firm as Moses. “You cannot have a tree, herzele. You shouldn’t even want to sing the carols. You are a Jew.” I turned the words over in my mind and on my tongue. What was it, to be a Jew in Birch Hills, Saskatchewan?

Though my father spoke of Jewishness as a special distinction, as far as I could see it was an inheritance without a kingdom, a check on a bank that had failed. Being Jewish was mostly not doing things other people did—not eating pork, not going to Sunday school, not entering, even playfully, into childhood romances, because the only boys around were goyishe boys. I remember, when I was five or six, falling in love with Edward Prince of Wales. Of the many arguments with which Mama might have dampened my ardor, she chose surely the most extraordinary. “You can’t marry him. He isn’t Jewish.” And of course, finally, definitely, most crushing of all, being Jewish meant not celebrating Christ’s birth.

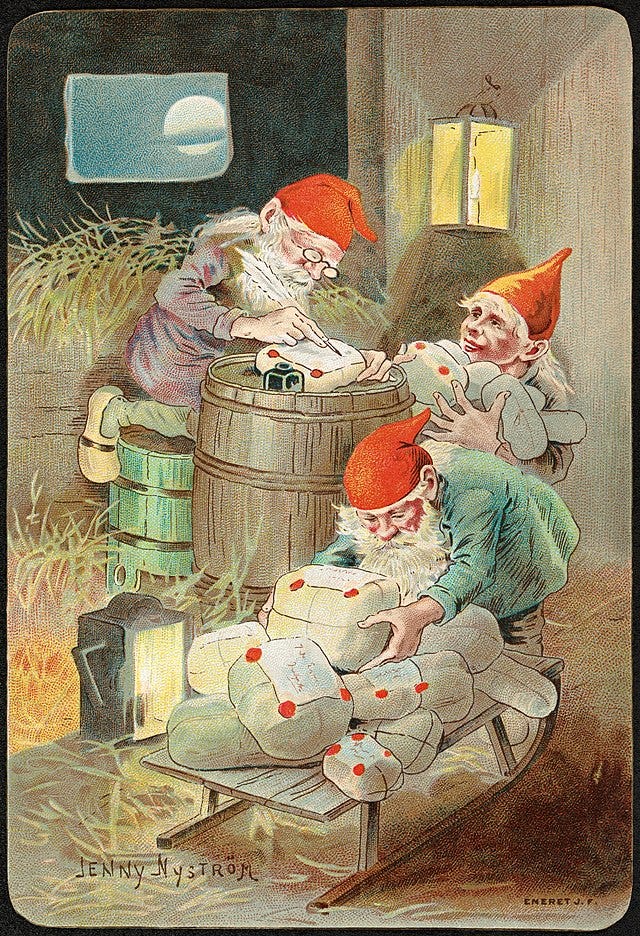

My parents allowed me to attend Christmas parties, but they made it clear that I must receive no gifts. How I envied the white and gold Norwegians! Their Lutheran church was not glamorous, but it was less frighteningly strange than the synagogue I had visited in Winnipeg, and in the Lutheran church, each December, joy came upon the midnight clear.

It was the Lutheran church and its annual concert which brought me closest to Christmas. Here there was always a tree, a jolly Santa Claus, and a program of songs and recitations. As the town’s most accomplished elocutionist, I was regularly invited to perform. Usually my offering was comic or purely secular—Santa’s Mistake, The Night Before Christmas, a scene from A Christmas Carol. But I had also memorized for such occasions a sweetly pious narrative about the housewife who, blindly absorbed in cleaning her house for the Lord’s arrival, turns away a beggar and finds she has rebuffed the Savior himself.

Oddly enough, my recital of this vitally un-Jewish material gave my parents no pain. My father, indeed, kept in his safe-deposit box along with other valuables a letter in which the Lutheran minister spoke gratefully of my last Christmas performance. “Through her great gift, your little Freidele has led many to Jesus.” Though Papa seemed untroubled by considerations of whether this was a proper role for a Jewish child, reciting The Visit made me profoundly uneasy. And I suppose it was this feeling, combined with a natural disinclination to stand unbidden at the feast, which led me, the year I was seven, to rebel.

We were baking in the steamy kitchen, my mother and I—or rather she was baking while I watched, fascinated as always, the miracle of the strudel. First, the warm ball of dough, no larger than my mother’s hand. Slap, punch, bang—again and again she lifted the dough and smacked it down on the board. Then came the moment I loved. Over the kitchen table, obliterating its patterned oilcloth, came a damask cloth; and over this in turn a cloud of flour. Beside it stood my mother, her hair bound in muslin, her hands and arms powdered with flour. She paused a moment. Then, like a dancer about to execute a particularly difficult pirouette, she tossed the dough high in the air, catching it with a little stretching motion and tossing again until the ball was ball no longer but an almost transparent rectangle. The strudel was as large as the tablecloth now.

“Unter Freidele’s vigele Ligt eyn groys veys tsigele,” she sang. Under Freidele’s little bed A white goat lays his silken head. “Tsigele iz geforen handlen Rozinkes mit mandlen…”

For some reason that song, with its gay fantastic images of the white goat shopping for raisins and almonds, always made me sad. But then my father swung open the storm door and stood, stamping and jingling galoshes buckles, on the icy mat.

“Boris, look how you track in the snow!”

Already flakes and stars were turning into muddy puddles. Still booted and icy-cheeked he swept us up—a kiss on the back of Mama’s neck, the only spot not dedicated to strudel, and a hug for me.

“You know what? I have just now seen the preacher, Reverend Pederson, he wants you should recite at the Christmas concert.”

I bent over the bowl of almonds and snapped the nutcracker.

“I should tell him it’s all right, you’ll speak a piece?”

No answer.

“Sweetheart—dear one—you’ll do it?”

Suddenly the words burst out. “No, Papa! I don’t want to!”

My father was astonished. “But why not? What is it with you?”

“I hate those concerts!” All at once my grievances swarmed up in an angry cloud. “I never have any fun! And everybody else gets presents and Santa Claus never calls out ‘Freidele Bruser’! They all know I’m Jewish!”

Papa was incredulous. “But, little daughter, always you’ve had a good time! Presents! What presents? A bag of candy, an orange? Tell me, is there a child in town with such toys as you have? What should you want with Santa Claus?”

It was true. My friends had tin tea sets and dolls with sawdust bodies and crude Celluloid smiles. I had an Eaton Beauty with real hair and delicate jointed body, two French dolls with rosy bisque faces and—new this last Hanukkah—Rachel, my baby doll. She was the marvel of the town: exquisite china head, overlarge and shaped like a real infant’s, tiny wrinkled hands, legs convincingly bowed. I had a lace and taffeta doll bassinet, a handmade cradle, a full set of rattan doll furniture, a teddy bear from Germany and real porcelain dishes from England. What did I want with Santa Claus? I didn’t know. I burst into tears.

Papa was frantic now. What was fame and the applause of the Lutherans compared to his child’s tears? Still bundled in his overcoat he knelt on the kitchen floor and hugged me to him, rocking and crooning. “Don’t cry, my child, don’t cry. You don’t want to go, you don’t have to. I tell them you have a sore throat, you can’t come.”

“Boris, wait. Listen to me.” For the first time since my outburst, Mama spoke. She laid down the rolling pin, draped the strudel dough delicately over the table, and wiped her hands on her apron. “What kind of a fuss? You go or you don’t go, it’s not such a big thing. But so close to Christmas you shouldn’t let them down. The one time we sit with them in the church and such joy you give them. Freidele, look at me…” I snuffled loudly and obeyed, not without some satisfaction in the thought of the pathetic picture I made. “Go this one time, for my sake. You’ll see, it won’t be so bad. And if you don’t like it—pffff, no more! All right? Now, come help with the raisins.”

On the night of the concert we gathered in the kitchen again, this time for the ritual of the bath. Papa set up the big tin tub on chairs next to the black iron stove. Then, while he heated pails of water and sloshed them into the tub, Mama set out my clothes. Everything about this moment contrived to make me feel pampered, special. I was lifted in and out of the steamy water, patted dry with thick towels, powdered from neck to toes with Mama’s best scented talcum. Then came my “reciting outfit.” My friends in Birch Hills had party dresses mail-ordered from Eaton’s—crackly taffeta or shiny rayon satin weighted with lace or flounces, and worn with long white stockings drawn up over long woolen underwear. My dress was Mama’s own composition, a poem in palest peach crepe de chine created from remnants of her bridal trousseau. Simple and flounceless, it fell from my shoulders in a myriad of tiny pleats no wider than my thumbnail; on the low-slung sash hung a cluster of silk rosebuds. Regulation underwear being unthinkable under such a costume, Mama had devised a snug little apricot chemise which made me, in a world of wool, feel excitingly naked.

When at last I stood on the church dais, the Christmas tree glittering and shimmering behind me, it was with the familiar feeling of strangeness. I looked out over the audience-congregation, grateful for the myopia that made faces indistinguishable, and began:

A letter came on Christmas morn

In which the Lord did say

“Behold my star shines in the east

And I shall come today.

Make bright thy hearth…"

The words tripped on without thought or effort. I knew by heart every nuance and gesture, down to the modest curtsey and the properly solemn pace with which I returned to my seat. There I huddled into the lining of Papa’s coat, hardly hearing the “Beautiful, beautiful!” which accompanied his hug. For this was the dreaded moment. All around me, children twitched and whispered. Santa had come.

“Olaf Swenson!” Olaf tripped over a row of booted feet, leapt down the aisle and embraced an enormous package. “Ellen Njaa! Fern Dahl! Peter Bjorkstrom!” There was a regular procession now, all jubilant. Everywhere in the hall children laughed, shouted, rejoiced with their friends. “What’d you get?” “Look at mine!” In the seat next to me, Gunnar Olsen ripped through layers of tissue: “I got it! I got it!” His little sister wrestled with the contents of a red net stocking. A tin whistle rolled to my feet and I turned away, ignoring her breathless efforts to retrieve it.

And then—suddenly, incredibly, the miracle came. “Freidele Bruser!” For me, too, the star had shone. I looked up at my mother. A mistake surely. But she smiled and urged me to my feet. “Go on, look, he calls you!” It was true. Santa was actually coming to meet me. My gift, I saw, was not wrapped—and it could be no mistake. It was a doll, a doll just like Rachel, but dressed in christening gown and cap. “Oh Mama, look! He’s brought me a doll! A twin for Rachel! She’s just the right size for Rachel’s clothes. I can take them both for walks in the carriage. They can have matching outfits….” I was in an ecstasy of plans.

Mama did not seem to be listening. She lifted the hem of the gown. “How do you like her dress? Look, see the petticoat?”

“They’re beautiful!” I hugged the doll rapturously. “Oh, Mama, I love her! I’m going to call her Ingrid. Ingrid and Rachel….”

During the long walk home Mama was strangely quiet. Usually I held my parents’ hands and swung between them. But now I stepped carefully, clutching Ingrid.

“You had a good time, yes?” Papa’s breath frosted the night.

“Mmmmmmm.” I rubbed my warm cheek against Ingrid’s cold one. “It was just like a real Christmas. I got the best present of anybody. Look, Papa—did you see Ingrid’s funny little cross face? It’s just like Rachel’s. I can’t wait to get her home and see them side by side in the crib.”

In the front hall, I shook the snow from Ingrid’s lace bonnet. “A hot cup cocoa, maybe?” Papa was already taking the milk from the icebox. “No, no, I want to get the twins ready for bed!” I broke from my mother’s embrace. The stairs seemed longer than usual. In my arms Ingrid was cold and still, a snow princess. I could dress her in Rachel’s flannel gown, that would be the thing…. The dolls and animals watched glassy-eyed as I knelt by the cradle. It rocked at my touch, oddly light. I flung back the blankets. Empty. Of course.

Sitting on the cold floor, the doll heavy in my lap, I wept for Christmas. Nothing had changed then, after all. For Jews there was no Santa Claus; I understood that. But my parents…. Why had they dressed Rachel?

From the kitchen below came the mingled aromas of hot chocolate and buttery popcorn. My mother called softly. “Let them call,” I said to Ingrid-Rachel. “I don’t care!” The face of the Christmas doll was round and blank under her cap; her dress was wet with my tears. Brushing them away, I heard my father enter the room. He made no move touch me or lift me up. I turned and saw his face tender and sad like that of a Chagall violinist. “Mama worked every night on the clothes,” he said. “Yesterday even, knitting booties.”

Stiff-fingered, trembling, I plucked at the sleeve of the christening gown. It was indeed a miracle—a wisp of batiste but as richly overlaid with embroidery as a coronation robe. For the first time I examined Rachel’s new clothes—the lace insets and lace overlays, the French knots and scalloped edges, the rows of hemstitching through which tiny ribbons ran like fairy silk. The petticoat was tucked and pleated. Even the little diaper showed an edge of hand crochet. There were booties and mittens and a ravishing cap.

“Freidele, dear one, my heart,” my father whispered. “We did not think. We could not know. Mama dressed Rachel in the new clothes, you should be happy with the others. We so much love you.”

Outside my window, where the Christmas snow lay deep and crisp and even, I heard the shouts of neighbors returning from the concert. “Joy to the world!” they sang,

Let earth receive her King!

Let every heart prepare Him room

And heaven and nature sing…

It seemed to me, at that moment, that I too was a part of the song. I wrapped Rachel warmly in her shawl and took my father’s hand.

What does this memoir spark in you? I’m listening. After hosting readers here for the past 14 months, I know you’ll have a lot to share. Is Christmas the most wonderful time of the year for you, or just the opposite? Have you ever been the outsider, hungry to belong? And what is belonging, anyway? Jump in, friends. We’re a good-hearted bunch.

Fredelle Maynard has been striding in and out of these posts for a while. Ghostwriting a column for Dr. Joyce Brothers, a pop psychologist she disdained. Teaching Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” to a classroom full of airmen who had never studied literature before. Finding the love of her life in middle age, while reeling from the end of her marriage.

Everything I post is free to read. I tip my entire collection of hats to those who’ve chosen to pay for a subscription, just to cheer me on. If now is the moment to join them, I’d be boundlessly grateful. Still, I can’t say it too often: There are other ways to speed Amazement Seeker on its way—and make me smile. Click the heart, share a post, join the conversation. I’m hosting family for dinner today and could be a tad slow to reply. You’ll hear from me, though. I wouldn’t deny myself the pleasure.

It’s been a joy to welcome you week after week. Whatever you celebrate, even if it’s time off to flop on the couch with a book, I hope it lifts your heart.

Your mom was a fabulous writer. I finished reading Raisins and Almonds about a month ago. I can't imagine growing up in a family with so much talent. Wait a minute. I did! Talent of a different sort, but talent just the same. I don't celebrate Christmas. I was raised in a Jewish family, so Hanukah was the primary observance. That didn't stop my father from hauling out his little artificial tree. He kept it in a slim box which he'd pull from a high shelf in his closet; it was about 2 feet tall, if that high. The tree was white and the ornaments were pink, white, and silver balls as I recall. Maybe explains my love of pink? Always as an accent, never overwhelming. My dad loved any excuse to give gifts. So, we did a funny Christmas and it was just about the presents and the stockings, crammed full of treats. It never really felt right to me, but we weren't religious Jews. It was more a cultural connection than anything else. But I have memories of my grandmother (the one who raised my father in a moderately Orthodox home) singing Raisins and Almonds to me as a child. I was always surprised that she had a lovely voice. It's the only song I remember her singing.

Your mother. You. Raisins and Almonds. Tree and Apple. I read your memoir, too, finished it 2 weeks ago. You do her proud, every single week with us. Thank you for sharing her work. Love to you, my friend.

https://youtu.be/x-W_DikODc4?si=215BxqQ66IAXPl4F

Oh my heavens. This is an astounding story. And utterly unforgettable. About families and love and trying to understand and not always getting it.

And your own words: “Typing the entire story for you, I touched her writer’s mind with my fingers. It seemed we were peers in conversation and that she, who died in 1989, had only slipped into the kitchen to brew another pot of mint tea.” So moving, too. And powerful.