The day we adopted our first dog, we slipped around his neck the red collar that told him he was ours. It soon acquired a collection of tags that jingled in time with his claws—the domestic music of our days for the next nine years and nine months. When all that clinking eroded the tags, Casey had to sit uncollared while we switched them out for new ones. His eyes darted, his body stiffened. Home wasn’t home without his collar, and he didn’t relax until the buckle clicked against his throat.

Before I loved a dog, I made quite a few reverential visits to a huge Alex Colville retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario. It was 2014, one year after the death, at 92, of a painter inspired by the animals among us—horses, crows, cats, the occasional sheep or cow. And dogs, above all. “Animals are angels,” he declared. In Colville’s vision of the world, it’s we humans who make all the trouble. Animals are innocent, but the worst of us bend and break their true natures to serve our own wills.

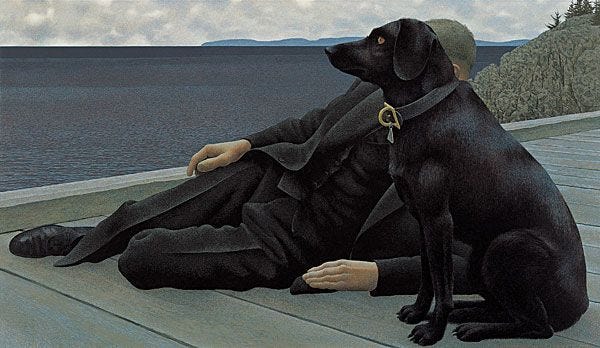

If I could take one Colville home, I’d choose “Dog and Priest.” The dog, a totem in fur, wears a vigilant expression and a thick leather collar with a single tag. The buckle gleams, its curve an echo of the priest’s ear. That ear and some graying hair are all you see of the priest’s head. Arthritic fingers tell you this man is getting on, but his face is a secret between him and Colville.

Every Sunday the priest greets his flock with the composed, familiar face they’ve been expecting. Colville lets him relax unseen in the posture of a daydreaming child, no service to give. His time has come to receive a service, the consoling nearness of his dog—the guardian angel whose majestic profile anchors the scene.

God has called the priest. Something far away calls the dog, whose red eye glows like an ember. With a poet’s attention to the nuance of every detail, Colville heeded the call of art. Call upon call, three claps on the bell of my heart.

When I was majoring in English and altered states, I studied George Herbert’s poem “The Collar.” Unlike juicier poets of his time, the 17th century, Herbert didn’t celebrate the pleasures of the flesh. His subject, faith, concerned me not at all. He had the skill to dazzle me with sultry odes to his mistress (did he have one?). But he chose, mystifyingly, to lavish his gifts on obedience to God. The stars of my course on the 17th century—John Donne, Andrew Marvell—were literary heartthrobs who seemed to flourish naked. Who could imagine Herbert without his clerical collar?

Back then I smoked a lot of what we called “grass.” I might have been pleasantly buzzed as the professor opened his book to “The Collar.” He sat on his desk, smiled indulgently on us 20-ish hedonists, and let loose a peal of poetry:

I struck the board, and cried, "No more;

I will abroad!

What? shall I ever sigh and pine?

My lines and life are free, free as the road,

Loose as the wind, as large as store….

I detected a little Bob Dylan in Herbert—the fiery, fist-shaking Dylan of “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” For a 17th-century cleric, he seemed almost cool—until the poem pivoted from striving to submission. Instead of reveling in freedom, bitter as it was, he yoked himself to the comfort—a false one, I thought then—of religious faith.

But as I raved and grew more fierce and wild

At every word,

Methought I heard one calling, Child! And I replied My Lord.At 20 I craved freedom more than anything but love. I came to see that love, if you’re going to stay the course, entails a degree of servitude. Bleary-eyed nights with an infant who would not be detached from my breast. Hard-won compromises with a spouse whose firm views didn’t always accord with mine. Weekends devoted to the cover-to-cover redesign of the magazine that, in my care, was like my most demanding, irresistible friend.

“Freedom 55,” a buzz phrase then, sounded good to Paul and me. But no sooner untethered from careers and parenthood, we discovered the downside of freedom—no one and nothing to need us with a daily, metronomic presence that nourishes more than it burdens. We adopted Casey and became a family again. Walks in all weather seemed a small price to pay for the cheerful slap of his tail against our legs, the coiled warmth of him between us on the TV couch.

It never crossed my mind that we’d see Casey through four and a half months of cancer. If I’d known about the stains on our Tibetan carpet and the box of doggie diapers in the hall, I’d have said, “Count me out.” Love is a collar I wore in gratitude. When Casey died, the vet listened to his great stilled heart and asked with the utmost gentleness, “Would you like to keep his collar?”

I hung Casey’s collar on the hat stand beside the door, where it called to me every time I headed out. Two months passed as Paul and I mulled the adventures we could plan without a dog. A leisurely swing through Japan and South Korea. Next winter in Spain. Road trips free of ruinous pet fees charged by so-called “dog-friendly” hotels. Then we realized, in the same moment, that we’d rather share our home with a dog than see the world.

The day we came home with the squirming fireball known as Chica, the hat stand sprouted a garden of doggish paraphernalia. It could barely accommodate Chica’s hoodie, leash and harness plus the winter headgear of two hat fanciers. Paul tossed me Casey’s collar: “Time to find a new place for this.”

I’m no good at catching balls, let alone collars. My memento landed on the floor with a jingle that summoned Chica. Round and round she spun, the collar gripped between her teeth. Her nails slid on the tiles as she shook the last of Casey. Everything’s a toy to Chica. All is right with the world.

Have you felt the tension between love and freedom? How did you resolve it? Whatever and whomever you loved, this is the place to share your discoveries. Your comments cheer me on, and I strive to answer every one.

Feel free to share this post—I’d be honored. Some of my most loyal readers found Amazement Seeker through a friend. If you have the inclination and the means, you could make me bounce around like a puppy by upgrading your subscription. Remember: “if.” I welcome all readers, paying and not.

Alex Colville, a poet of the brush, had more to say about the joy and woe of living than I could possibly touch on here. His portrayal of a long marriage deserves a whole other essay. To learn more, start with this essay and his official site. Still in the mood for art? I often write about artists who inspire me—Bonnard and Marisol, among others. Do poke around. The whole archive is yours for the browsing.

I can't imagine my life without dogs. I've had one or two dogs non-stop from the time I was 21...43 years? How is that possible. We tried to have them when I was a kid, but my parents didn't know how, and expected me, at 7 to be in charge of a 75 pound golden retriever who loved to chase squirrels while dragging me through our neighborhood on my belly because I was afraid if I let go of her leash I'd never see her again. A good case of road rash and a neighbor kid pushed through the glass of our French doors by our enthusiastic Pepper (yes, Pepper Tepper) put an end to her residence in our home. The loss was so deep for me that I vowed to have pups when I was a grown up! So, yes. I've kept my word. I love my little life-mates. Nothing as good as a cuddle with a pup. Nothing comes close. xo

Thank you for this, Rona. I haven't really cried since Sugar died just over a week ago. I said it was all good. She was old and so tired. But your words finally released my tears and that felt right.