A Tale of Two Sisters

Rivalry and resentment used to pull us apart. Love is stronger.

Happy National Sisters Day! I’m celebrating my sister, Joyce Maynard, with a new version of an essay first published in MORE alongside Joyce’s companion essay. If she hasn’t posted it on her Substack, you can find it here.

A marvelous thing happened one Wednesday morning in October, just after I blew in from yoga class.

My husband said, “Your sister called.” The very thought of a message from Joyce has been known to make me quiver with alarm. I remember the fierce, proud love that the sound of her voice unlocks in me. Then I brace myself for a replay of our ancient, crazy-making script (her cajoling, my refusal; her tears, my lofty sigh).

That morning after yoga, I forgot about those past conversations. I poured myself a coffee, settled in my favorite armchair and called Joyce back at her house on a mountainside in California, two time zones away from my condo in downtown Toronto. “Happy birthday,” she said.

I’d forgotten. It was October 20; I had just turned 57. And something in me had softened. It had happened so slowly that I missed the first signs, just as I missed the first hint of lines around my eyes. At 57, I had finally found the good sense to embrace possibility instead of standing guard against pain.

My little sister was almost 53 (although in my mind she remained the pesky kid who used to borrow my clothes without asking). She has always remembered this day, no matter where in her travels she has just alighted, or what kind of commotion she’s embracing with her customary zestful resolve: a pie-baking class in her kitchen, a solo campaign to bring girls’ basketball to Guatemala, a book tour of 18 cities in two months.

I’m reserved; she’s flamboyant and expressive. I fret over every decision; she’s bought houses faster than I’ve bought shoes. I’ve been married my entire adult life to my first love and best friend; she’s been divorced, widowed and many times partnered.

She has something I’ve always lacked: irresistible, effortless magnetism. I knew it from the moment she entered my life. Our parents exclaimed at her beauty while I slunk away with the book of fairy tales no one would read to me.

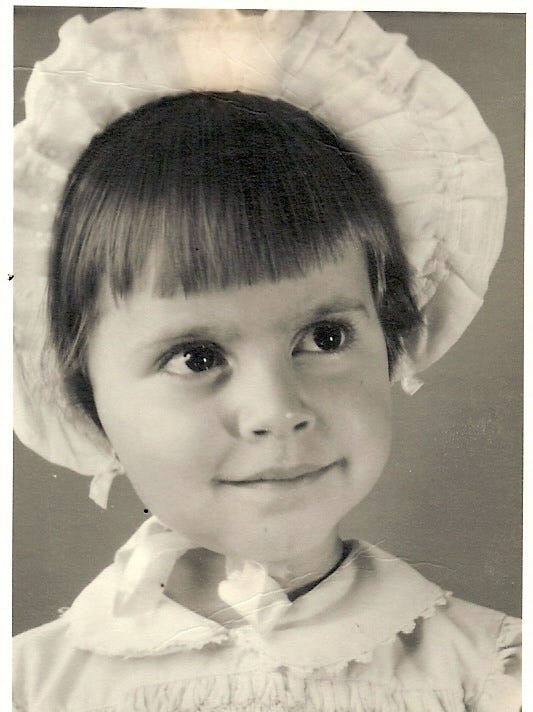

I thought I wanted a baby sister; I had name picked out — Daphne, from my favorite Greek myth, about a nymph who prizes nothing more than her freedom. When Apollo falls in love with Daphne, she’s so determined to avoid his embraces that she turns into a tree. Daphne was my kind of heroine. Like her, I shrank from embraces, unsettling our mother. My baby sister was a cuddler. She curled herself against our mother’s bosom as if she intended to stay there forever.

She’d barely arrived when I announced that she didn’t look like Daphne. She would need another name. How about her middle name, Joyce?

One week old and she’d already lost her name to a controlling older sister. But of course I was nursing a loss of my own. Until Joyce came along, I too had been something of a charmer. I told stories that delighted family friends—until I went quiet, just like that.

Our contrasting traits became the stuff of family legend. Joyce was the cheerful, try-anything dynamo, ready to throw her arms around the world. I was the anxious, morose one, Eeyore to her Piglet. When our mother served pie, I scrutinized the slices, ready to protest if Joyce had a crumb more than I did.

At least I had talents Joyce didn’t possess: I drew, danced and wrote elaborate fantasies. Our parents exclaimed at my imaginative powers. Wouldn’t you know, Joyce set out to leave me in the dust. She wrote one-woman variety shows and staged them in our living room, complete with spoof commercials, while our parents applauded with feverish delight. They’d been craving the distraction that Joyce provided: Our father was an alcoholic, prone to rages and impenetrable gloom. We never talked about the reason for “Daddy’s moodiness,” and high-spirited Joyce could create the illusion that all was well in our family.

With my melancholy nature and constant complaints about imaginary illnesses, I compounded our parents’ unspoken desperation. Yet Joyce looked up to me, eager to hear my pronouncements on dollhouse décor and the rules of Monopoly. She made an acceptable playmate for a boring afternoon — but only until my friend Christina dropped by. Then I’d slam my bedroom door in Joyce’s face with a shiver of triumph. Our mother used to plead, “Rona, be patient with your sister.” Fat chance. Joyce had robbed me of enough already.

She would eventually steal my favorite author, or so it seemed at the time.

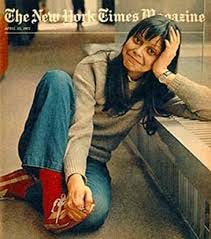

Nowadays, even people who don’t know my sister often know one notorious detail of her history: her brief and wrenching relationship, at age 18, with the then 50-something author of The Catcher in the Rye. He had to meet the winsomely precocious sprite—barely out of high school and already a famous writer—whose photo he’d seen on the cover of The New York Times Magazine.

No one called out J.D. Salinger for preying on a teenager. No one sounded an alarm when Joyce dropped out of Yale and followed him to his lair on a New Hampshire hill, there to subsist an sliced cucumbers and barely cooked lamb (he enforced rigid dietary rules). In our mother’s exultant vision of the future, Salinger would crown Joyce—and by extension the Maynard family—with literary glory. She could hardly wait for the wedding and the grandparental visits from “little Salingers, bringing their organic lunches.”

She took a dim view of my own marriage to the fellow student who is still my husband. Too young, not ready. When we fought, I remembered the chill of her judgment. My ancient wound began to bleed.

The year I turned 11, our mother fell dangerously ill with pneumonia. One night I stood in the doorway of Joyce’s room, watching her sleep. She had buried her face in a pile of stuffed animals that filled half the bed. If our mother died, we’d be left with our father, who burned the pots and drove drunk. At seven, Joyce shared my secret fear. Still, it didn’t cross my mind to clear a place for myself beside her and put my arms around her. That would have forced me to admit the terrible bond of our helplessness.

Our mother didn’t die of pneumonia. She died of a brain tumor nearly 30 years later, in the pretty Victorian house that her second husband had bought for her. She had moved to Toronto to be with him. Joyce and I had already faced our father’s death, but the loss of our mother, who had always been the steadying hand of order in the family, threw us into a maelstrom of anger. We reverted to the roles we had played as children vying for our mother’s love.

Joyce, at 35, was the buoyant creator of cheer in the midst of anguish. Arriving in Toronto with her computer and a jumble of CDs, she took on our mother’s care with the same full-tilt multi-tasking that she’d formerly brought to her living-room variety shows. She decorated our mother’s breakfast tray with posies from the garden, pushed the wheelchair in the park, baked her special poppyseed cake, smiling as if this were an ordinary family reunion.

Meanwhile I searched for a quiet place where I could speak with my mother before the tumor silenced her forever. About to turn 40, I still longed for her attention. Hands-on care was not my strength, so I would sit with her in the garden, scribbling furiously as she dictated farewell letters to her friends.

The crisis flared as our mother grew weaker. My stepfather and I believed she needed round-the-clock nursing care. Joyce was determined to remain the primary caregiver even though she was running out of strength. Her smile tightened at the corners as the house throbbed with her efforts: the whizzing Mixmaster, the increasing struggle to get our mother down the stairs and into the wheelchair.

When I tried to discuss this with Joyce, she would burst into tears and leave the room. She thought I was cold and ungrateful for all her hard work; I thought she was hysterical. In my way, I too rode a surging tide of emotion that kept pulling me under. I remember telling Joyce, with ferocious conviction, “Your behavior is making me physically ill.” I remember my husband telling me, “When you talk about your sister, an ugly look comes into your eyes.”

I cringed, knowing he was right. But I also knew — along with my stepfather and a number of friends — that our family couldn’t go on like this.

Our stepfather wrote Joyce a letter setting firm conditions on her time with our mother: when she could visit, where she would stay (with a neighbor, not in the house). He had my support. In Joyce’s eyes, her own sister had betrayed her. Even worse, I was leaving her alone in the world. The letter reached Joyce while her husband was ending their marriage. She later told me, “You did violence to me.” I did, and knowingly — but also to myself. I felt not unlike the desperate outdoorsman who, pinned by his arm beneath a fallen tree, took out his utility knife and cut off the arm.

I didn’t want to see Joyce, but I had to. Our mother’s death soon required us to empty our mother’s house, which brimmed with her copious possessions. While Joyce and a friend drove to Toronto in a van, I made a number of executive decisions, none involving items she’d mentioned. I promised the teak table to a woman who had loved our mother and warmly remembered her dinner parties. It turned out that Joyce had other plans. She wanted to give the teak table to her friend, but I refused to break my promise. Joyce bristled with tearful fury, then took off.

At the time her reaction made no sense to me. How could someone who didn’t know our mother trump someone who had cherished her for years? I thought Joyce and I had been fighting about the claims of two people outside the family, when the real issue involved a power struggle between ourselves. As the older sister, I assumed the right to make certain decisions, like a queen donning her mantle.

We had entered our most difficult years. Until our mother’s death exposed the unresolved conflict between us, we could trade family gossip on the phone for an hour at a stretch. This happened just often enough to create the illusion of closeness, although we had never been close. Now the Maynard family had shrunk to ourselves.

We were both in our forties when Joyce called to say she was coming to Toronto. To Die For, a movie based on one of her books, had been chosen to open the Toronto International Film Festival, and the producers were flying her in for the gala. Mixed emotions tugged at me — eagerness to see Joyce, fear of her expectations. She’d want to stay at our house, but we’d already tried that once and I had felt overwhelmed by her sheer nonstop busyness.

My home has always been my refuge from the world; she transformed it, with the best of intentions, into backstage on the opening night of a mega-musical. I remembered Joyce in my kitchen, with the phone under her chin, a pastry blender in her hand, flour everywhere and the stereo at full volume, juggling her complicated schedule while I waited for things to calm down so that I could start the rest of our dinner. She’d been baking me one of her transcendent pies, so it seemed churlish to not to be grateful. But if I let her stay with me again, we would both pay the price for my annoyance. Could I help with her hotel arrangements?

No. She wanted to stay with us. Was that so much to ask from her only sister? Her voice trembled; I knew she was crying.

All night I agonized. I couldn’t bear to hurt my sister — or to lose myself placating her. Then I remembered the hotel at the end of our street. My husband and I would stay there during her visit, leaving Joyce the run of our house. We’d come home in the morning to have breakfast together; we’d take Joyce out for a pre-gala dinner. That’s exactly what we did, and to me it felt absolutely right. But not to her. She couldn’t let the matter drop. At my kitchen table, she pressed me to explain why I wasn’t the welcoming sister she wished I could be. If I really loved her, wouldn’t I want to share my home with her?

Some time after that, we stopped speaking. I’d been on my way to California, hoping we could meet for dinner, when she e-mailed me to say that she would have to pass. My presence in her life — skeptical and distant instead of ebullient and accepting — caused her too much pain. Better we should love each other from afar. Her decision saddened me, but I was not about to argue.

In the years of our silence, I’d have said I didn’t miss her. I had another challenge on my mind: editing Chatelaine, where my monthly column had won a loyal following. Readers often wrote, “I feel as if you’re my sister.” What would they think if they knew I had a sister with whom I no longer spoke?

Meanwhile thoughts of my sister kept tugging at me. Sometimes between meetings I would visit her website and click on “A letter from Joyce.” I must have been on her mind, too, because one day she called to ask, “So whose idea was it that we weren’t speaking?”

“Yours, of course.” Older sister to the core, I had to have the last word.

Looking back on my life as a sister, I’m struck by the importance I’ve attached to the four years between Joyce and me. When we were growing up, four years meant the difference between ABCs and cursive writing, ankle socks and pantyhose. Four years were the mountain from which I looked down on a know-nothing kid. I cultivated an air of regal authority that served me well in my editing career. Junior staff understood that if they let me down, I would give them “the look,” which I had practiced to withering perfection on Joyce.

At 55 I left my editing job to become a full-time writer—my sister’s career for more than three decades. I no longer needed “the look,” any more than I needed the designer suits that now hung at the back of my closet.

Wondering what Joyce was doing, I sat down at the computer and clicked on “A letter from Joyce.” There I read — along with untold thousands of strangers — that Joyce was moving to New England. Then we’d be road-tripping distance apart.

Suddenly it struck me: I missed her. Wouldn’t you know, she’d been missing me, too. A day or so later, she called on my birthday. She’d already changed her mind about moving to New England, but her bright cascade of laughter was just as I remembered.

The wonder to me now is not the rage and resentment that divided us for so many years, but the staunch, insistent love that keeps pulling us together. Joyce and I are equals now, two accomplished, seasoned women who, between us, have sent four grownup children into the world. Perhaps we’ve always been more equal than I knew, both shaped by the same endearingly troubled family as no one but the two of us will ever comprehend. I saw her feigned sprightliness; she saw my misery. Now we’re finally free to choose which aspects of our childhood to abandon, and which ones to mine as we become our best selves.

Daphne was the nymph who ran away from love. When I took that name away from Joyce, I thought I was getting my own back. But here’s something I didn’t know. My name, Rona, is derived from the Hebrew word for “joy.” So in essence we share a name. I like knowing this. It gives me hope.

Do you have a sister who tugs like no one else at your emotions? Or a sister you’re missing today? Let’s make a sibling fest of your comments. Brother stories welcome too—I don’t want to leave anyone out.

Speaking of stories, do you have one you’re burning to write? I now offer coaching services for pros and beginners alike, with a discount for paid subscribers. Details here.

All my work is free to read, so browse and share to your heart’s content. You might enjoy my take on revisiting The Catcher in the Rye a lifetime after it won my heart. A deep bow to those of you who choose to pay for no reason but the pleasure of cheering me on.

This is a brave, wise and poignant essay, Rona, accomplished with your usual grace and elegant style. It will touch many hearts. The story of my late sister and me is too painful to tell here, but I have written about it, published a tiny bit of it, and got written out of my mother’s will as a result - with prodding from an unprincipled brother.

I remember the original More article. Over the years Joyce and I discussed our relationship with our sisters. I’m an elder sister by 3 1/2 years. My mom was always begging me to be more tolerant of my younger sister and suggesting I take her along even when we were in our twenties. When our mom died at the young age of 57 we grieved together and still do. We’re very different and I will be shaking my head at her my entire life.