Never Tell Anybody Anything

Holden Caulfield stole my teenage heart. Sixty years on, he's not the same anguished rebel.

Today’s essay has been ripening for more than 60 years. I can’t wait to share it, but first, a news flash. Some of you have asked if I offer coaching services. Starting right now, I do. Details here. Before I sign you up, we need to agree the fit is right. Let’s find out in a free 20-minute chat. And now, on with the main event.

Sometimes I really want to hear about it. The cab that smelled like somebody had tossed his cookies in it, the baseball mitt covered with poems in green ink. The entire teeming cast of losers and liars, phonies and pure-hearted children, not all of them alive, who perplex a lonely kid named Holden Caulfield—cast out of one more prep school to search for connection in the chilly hubbub of Midtown Manhattan, just before Christmas.

I needed a purse-size book for the plane when The Catcher in the Rye turned up on my bottom shelf. Instead of a bookmark, I slipped a pen between the pages. The lines that riveted me at 75 were not the ones that made me swoon with recognition at 13.

I read in haste back then, nodding along at Holden’s every smartass quip about corrupt and clueless grownups. Now I read to discover, pen in hand. J.D. Salinger’s first book, which has been selling up a storm since 1951, is not the same novel that reflected my private anguish long ago. The towering question that it asks is one that faces every so-called grownup. In a terminally broken world where people die, disappear and disappoint, to care is to risk your heart. You must choose, over and over, between the cocoon of retreat and the wide, windswept plain of commitment.

My mother introduced me to Catcher, as she had all manner of books from Peter Rabbit to the poetry of Dylan Thomas. She had noticed the sign on my bedroom door: “PROTEST AGAINST THE RISING TIDE OF CONFORMITY.” She could have picked a fight but chose to play along. I’d like this book, she predicted. A modern classic.

I had broken up with classics, and so had Holden Caulfield. He declared himself in the very first line: “If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.”

One sentence, and I was in love. Oh, Holden, Holden. The truth is all I want to hear. That David Copperfield crap is for fusty old know-it-alls, not seekers like you and me. Rona and Holden forever.

My parents belonged to a Dickens club in which people read aloud from the likes of David Copperfield. Before I turned my back on Copperfield, I tore through it as I did every book. I didn’t know it at all until my husband downloaded an audio version and got us listening together, as families used to do in Dickens’ day. Dickens wrote for the voice, and the entire novel sparkled. By happenstance, the Copperfield adventure overlapped with my return to Catcher. And I noticed how the two books mirror each other.

Copperfield, Caulfield. Two bereaved innocents adrift. David parentless and abused by the cruel, joyless Murdstones. Holden mourning the death of his younger brother at 11, and the sellout of his gifted older one, a writer on the make in Hollywood. Both looking back on the trials that formed them—genial David from a hard-won and happy later life, disaffected teenage Holden from a hospital ward in the aftermath of a breakdown.

David was born with a caul, a piece of the amniotic sac wrapped around his head. It was sold for its supposed protective powers against drowning. Young David’s lucky charm is an open heart. By trusting good souls, he creates a family of choice that stands by him when his judgment fails. He lets a false friend take advantage, marries a lovely illusion instead of the true match readers cheer for. Hope can blind him, yet in the end it sees him through.

Holden, the anti-David, trusts no one. By expecting that others will fail him, he all but ensures that they do. He has one shining light: his devoted kid sister Phoebe, the antidote to all things adult and phony. Phoebe takes belching lessons from a pal, a detail I missed in my teens. Now I love her for it.

Until Holden entered my life, I couldn’t conceive of any loneliness greater than mine. The few friends I had, I lampooned in my journal. Holden, master of snark and “lonely as hell,” has no friends at all. He looks for compassion in the wrong people, from cynical bar flies to a cheating prostitute and her pimp. He considers jumping out a window but holds back for fear of “stupid rubbernecks looking at me when I was all gory.”

Holden has seen what becomes of jumpers. At Pencey Prep a gang of bullies locked their prey in his room and did their worst, driving the hapless boy out the window. He happened to be wearing a sweater he’d borrowed from Holden, who ran to the scene. Holden doesn’t tell you he could have been that boy, lying in his own blood as onlookers shrank from his body.

In my teens I didn’t know that suicide is a killer of teens—now second only to accidents—or that bullying can be the cause. No one talked about suicide then. Adolescence, in the media’s version, was the age of necking at the drive-in and dancing to the Top 40. Holden told the truth about misfits like me. I craved his misery as the jilted crave the same breakup song on repeat. Yet dying of misery never crossed my mind. In spite of everything, I wanted to live. I clung to the hope that any day I’d meet a soulmate like Holden. To tide me over, I counted on a secret stash of vodka. Smirnoff: same brand my father hid in the attic studio where he painted.

Five years ago, in the loneliness of lockdown, a bright eighth-grader in my city went AWOL from virtual school. Unlike many disaffected students in the global multitude of the missing, she confided in a teacher I’ll call Amy, who tried to win her back. The girl had just discovered The Catcher in the Rye. She lived in a home without books; now a world of discovery beckoned. Could the teacher help her find the rest of J.D. Salinger’s books?

Amy put out a call to a local Facebook group. Members couldn’t wait to share their Salinger books. One woman offered to bike over with a rare prize: a sweatshirt featuring Catcher’s original cover. Within a week, the student was back in class, writing poetry. As Amy told the group, “She was on fire.”

Chalk it up to the Catcher effect. Yet book banners can’t leave Catcher alone; Holden’s profanity offends them. I guess they didn’t notice how hard he tries to rub out “Fuck you” graffiti. He worries that if he dies (yes, he does say “if”), someone will carve “Fuck you” on his tombstone. His mouthiness is nothing but a posture, a brittle defense against his longing for someone to care about the real, vulnerable Holden.

Holden once had a young teacher who cared about the boys at Pencey Prep. When the bullies’ victim jumped out a window, Mr. Antolini wrapped the dead James Castle in his own coat and carried him to the infirmary. “He didn’t even give a damn if his coat got all bloody.”

Four pages separate Holden’s first sight of the body from Mr. Antolini’s reverentially tender ministrations. By circling back to the scene, Salinger heightens its impact. He won’t let the thinking reader turn away. What I see now, with a grandson the dead boy’s age and a lifetime behind me, is not what I saw at 13. Every book that moves me turns the earth of memory.

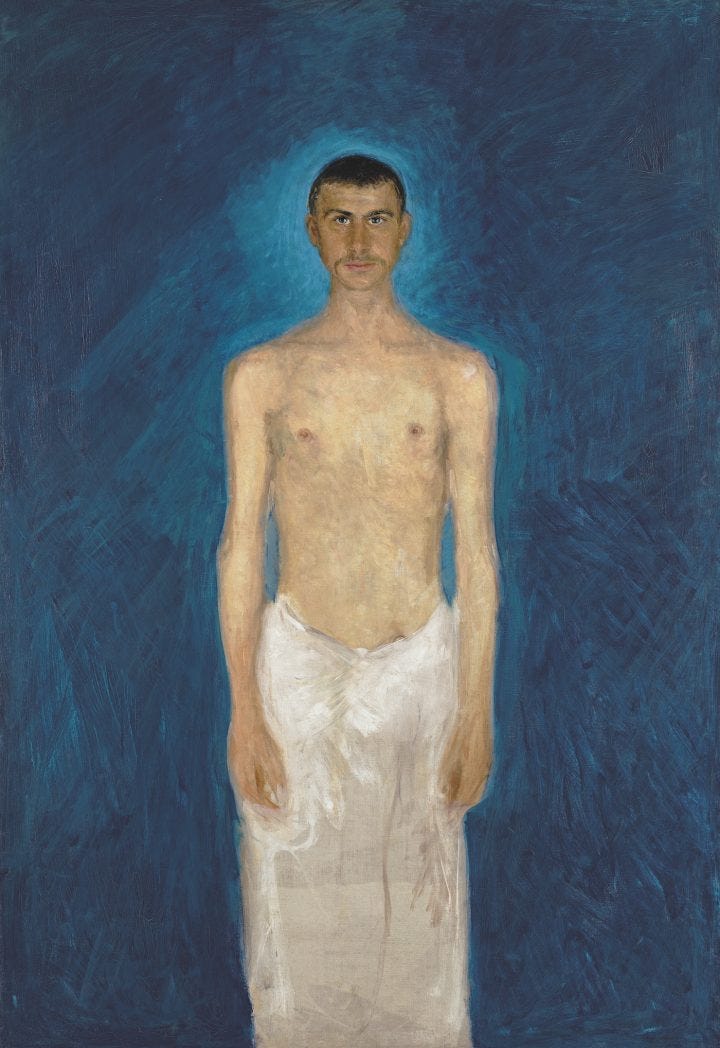

I’ve looked at art far and wide. When Mr. Antolini holds young James Castle in his arms, I see pietà paintings: Christ in the arms of his mother. Passion, to a Christian, means the suffering of Christ. Adolescence, to a lonely kid with tunnel vision, can feel like a passion play with a cast and audience of one.

I’ve never yearned for anything the way, in my teens, I yearned to be seen, heard and treasured. Never feared anything the way my young self feared letdown and betrayal. I had no sense of proportion. Fail me once, and you plummeted to a darker realm in my private circles of hell. In Holden Caulfield, I recognized my thorny, flinching self.

While hurtling toward the bottom of his tailspin, Holden fetches up at Mr. Antolini’s apartment. No other grownup in his life has ever done the right thing when it counted. True to form, his host invites him to spend the night. But this kind man is not an unblemished font of inspiration. Mr. Antolini has been drinking.

In his cups, he rambles about Holden’s keen mind and where an education could take him. “[Y]ou’ll find that you’re not the first person who was ever confused and frightened and even sickened by human behavior…. Many, many men have been just as troubled morally and spiritually as you are right now. Happily, some of them kept records of their troubles. You’ll learn from them—if you want to. Just as someday, if you have something to offer, someone will learn something from you.” Change “men” to “people,” and he’s right on the money.

Then Holden beds down, and alcohol gets the better of Mr. Antolini. He begins to stroke his former student’s head, which Holden perceives as “perverty.” I did too, as recently as 20 years ago. Where I once saw an advance, I now see a drunk’s fumbling attempt to plant the seed of wisdom in the mind of a desperate kid. But whatever his motive (there’s a case for both interpretations), Holden bolts. He’s done with Mr. Antolini.

Catcher’s greatness lies partly in its mystery. I could read it every year for the rest of my life and never drain the cup. Holden signs off as he begins, with lines that tug at me and won’t let go. Looking back on the quest that drives his tale, he yields to a baffling affection for the characters, even the pimp who stiffed him and then slugged him. “Never tell anybody anything. If you do, you start missing everybody.”

Twenty years ago, I predicted nothing good for Holden Caulfield. I just knew he was choosing retreat over commitment. I can’t write him off anymore. At 16, binge-drinking late one night, I called a girl at my school who seemed to have friendship potential. A grownup answered, scorching me with revulsion: “I don’t know who you are or what you’re after, but you’ve got a hell of a nerve to call like this.” If you want to know the truth, I had no clue myself who I was.

But here I am, telling you the story without shame. One more messed-up kid who survived adolescence and wouldn’t go back for anything. Holden has a tribe, and it is us. A living marvel.

What about you, Amazement Seekers? One of Holden’s tribe, or can’t stand the entitled little jerk? Bring it on! If some other book has grown with you over time, I’d love to know.

I’ll answer every comment, and Holden would hate me if I break my promise. So you can bet I’ll circle back to make sure I didn’t miss anyone. Every time a reader cares enough to chime in, I know I’ve done something right.

A small circle of readers care enough and have the means to pay for their subscription. You are my rainbows, and I couldn’t be more grateful.

I tried Catcher at least 3 times, maybe more, and I never could finish it. I couldn't stand Holden. It's so far back I can't remember exactly why, but I think I found the whining of such a privileged boy tiresome. (I never got far enough to know why he was so unhappy.) I know that a voice such as his was groundbreaking, but by the time I encountered him that kind of narrator was fairly common. The railing against conformity that I held close was Sinclair Lewis's Main Street. (I guess I was an odd duck of an 80's teenager.) You're inspiring me to find a copy of that and see how it lands now.

All I could think of when I started to read this was your sister. Don't you read this book differently since Sallinger played such a negative role in your sister's life?