What I Wish I Could Tell My Gay Boyfriend

You tried to desire me. I resented you for failing. Now I see the real you in all your tenderness and talent.

Hey, friends. Do you ever wish you could have a heart-to-heart with someone from long ago—someone you misunderstood at the time? Me too. Here’s the story of someone I reluctantly dated back when Sergeant Pepper was new. I’ve been working on this one for years, but it didn’t feel right until I reframed it as a letter. Do you have something to say to a person from your past? Keep the memory close as you read, and meet me in the comments.

Dear Jerry,

I had to see you, so I tracked you down to the cinderblock room online where it’s still 1989 and you’re still lecturing on Hamlet to an audience older than you ever got to be. Your hands fly as you make a point; your eyes flash behind outsize tortoiseshell glasses. Anyone would think you had years to make your mark, your hair lush and curling at the collar. Maybe your colleagues meet their students in jeans and work shirts; you have dressed for a great occasion in jacket, tie and a sweater vest that might be cashmere, not that I can tell from a video this grainy.

My mother taught you well in high school. She used to call teaching a performance, and you, old friend, hold attention like the Tom Hanks of the classroom, your craft seriously honed and lightly worn. You pitch forward in the plastic bucket chair as if about to leap out of it. You’re a man in love—with Shakespeare, with theater, with teaching rapt oldsters who may never have entered a university classroom until Dr. Jeremy Richard made them welcome. You look no older than you did at your prom, only more magnetic.

Remember how it felt to wait for love with a yearning that beats against your ribs like a wild thing desperate to escape? This was our bond, our secret, our shame. I would lie in my bed and imagine rocking it with the fantasy lover known as Adam, who adored me and touched me where no one ever had, not even myself, because bleeding from that place made it dirty. Adam’s touch would make it beautiful. He clearly wasn’t you, but you were the only one who asked me out—my mother’s favorite, plucked from her creative writing class, at a school in the next town, to meet her brilliant daughter, just 16 and already a nationally published writer.

You envied me but I wasn’t sure you liked me, not in the way that mattered.

Our house dazzled you. My father’s art on every wall, more books than you’d seen anywhere but a library—Iris Murdoch, James Baldwin, John Updike, the entire English canon. My mother, Dr. Maynard of the slashing red pen and tart ripostes, cooking Julia Child’s boeuf bourguignon for your pleasure (your mother served Hamburger Helper). You clearly envied me but I wasn’t sure you liked me, not in the way that mattered. “He’s so well-spoken,” my mother said. “And gifted. He’ll do well at Harvard.”

If anyone cool had asked me out, I never would have dated you. Cool guys read Ferlinghetti and chose Bob Dylan as their sage; you were mad for Lord of the Rings and Judy Garland. You once skipped down my street singing “We’re Off to See the Wizard” at full voice, heedless of the spectacle you made. Unlike every other teen I knew, you didn’t seem to care about pleasing anyone. I admire that now, but at the time it made me cringe. At least none of my schoolmates overheard your favorite expression, “Oh, my stars and garters,” or knew your reputation at your own school, where you’d been called every name for gay. I had girlfriends there who told me about your first lover, the actor you met in a summer stock company. You and I pretended I knew nothing.

Cool guys took their girlfriends parking. You had no drivers’ license and I was not exactly your girlfriend. Makeout buddy, that’s what I was. My parents had a furnished basement apartment that often sat empty because of its dollhouse proportions and head-grazing ceiling. On a metal cot covered with a cheap madras bedspread, we would shut our eyes tight and rub against each other, your hard-on digging into my thigh. Pretending you were Adam never worked—Adam’s hands would have roved underneath and between but yours drew back. You must have been pretending I was someone else, but my body felt all wrong. We gulped at each other and turned away hungry. The cot would groan and creak with our exertions. After one too many trysts in the apartment, it finally collapsed with a thud that shook the walls.

“Rona?” My mother, from the head of the stairs. To my horror, she’d been there all along, in a huddle with my younger sister (“Listen: They’re making out!”). The broken cot made her smile with indulgence. About time a boy rolled her daughter in his arms—a respectful boy who would leave my virginity intact. She’d heard the rumors about you and the actor, but persuaded herself we made a charming couple. "Don’t listen to gossip,” she’d told me. “When you’re young, it’s normal to experiment.”

Normal. How would either of us qualify? You would desire a girl. I would be desired by a boy. Love could wait. Perhaps you believed that in all the world there existed one pilgrim soul you could love. You can bet I believed this of myself. In the short term, I’d settle for desire. You seemed to be my only prospect. And against all the evidence that you could not desire me, I had not entirely given up.

I hated you for leaving me on the ground with my clothes bunched up around my waist, but not as much as I hated myself.

That night you took me to A Man and a Woman, we left the movie theater with nowhere to go. I was on fire for Jean-Louis Trintignant as a debonair racing-car driver, but disdained everything about the movie from the sliver of a plot to the saccharine theme song, no words except la-la-la. You insisted on singing it. “Wasn’t that romantic?” you said, taking my arm to walk me home. Trintignant would have done it like a lover. You impersonated a lover. On your arm I wasn’t real to myself. I had become a torrent of longing that would drench us both any minute.

An impulse came over me. You were still singing la-la-la as I led you into the dark woods along our route. I found a bed of decaying leaves and pulled you onto it. We had dressed for late fall, both of us in wool coats, but I yanked mine up and shoved your bare, cold hand between my legs with a boldness that dismayed us both. You jumped to your feet.

I silently called you every name for what we both knew you were. You fairy, you queer, you fag. I hated you for leaving me on the ground with my clothes bunched up around my waist, but not as much as I hated myself.

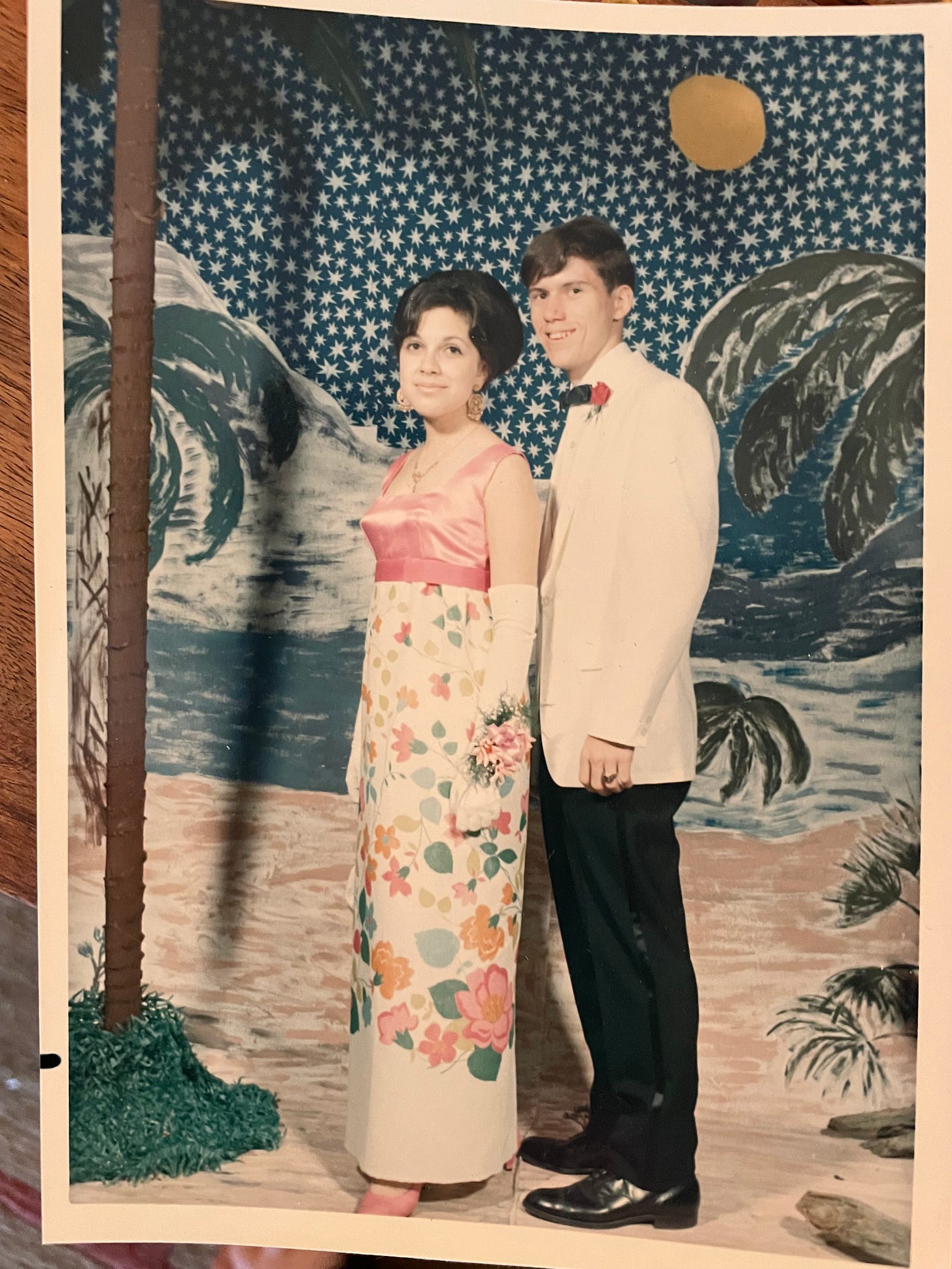

After that night in the woods, we never spoke of what we knew. You took me to your senior prom in a rented dinner jacket that hung on you. I wore a gown my mother had made, with satin shoes dyed to match and my hair teased into a beehive fit for Seventeen magazine. For once I looked like a girl who frolicked at beach parties while the Top 40 blasted from transistor radios.

It was 1967, the summer of love about to blossom. I couldn’t wait to forget that you and I had ever dated.

When I heard that you had died of AIDS, at 40, a wave of grief came over me—mostly for the future that should have been yours as a gifted professor of English, but also for the friendship that might have been ours long ago. We had much to share, two misfits in search of belonging, but we kept it under lock and key. Can you recall a single honest conversation between us? I used you, Jerry. Weren’t you using me too?

“Every death is like the burning of a library,” said Alex Haley, adapting an African proverb. The Book of Us may be gone, but your death didn’t follow quite the usual pattern. The University of Connecticut library in Stamford, where you taught for more than a decade, named its library in your honor. I used to think you were the opposite of cool. But what could be cooler than your name on a temple of learning?

I forgive us our youthful desperation. Maybe you beat me to it. Teaching Shakespeare, you plumbed the quirks and conundrums of the heart. As you tell your students in the Hamlet video, there’s a difference between what really happens in the play and what the Prince of Denmark believes to be true. Shakespeare’s richly rendered characters, like any and all of us humans, can be read in a multitude of ways and are ever-evolving. As you say, “They are characters who are still capable of surprising themselves.”

You have about a year left to live.

With the video muted, I can turn my attention to your body and its ways, the movement of brows, hands, torso. You’re not only speaking but dancing. This isn’t how I remember you, but back then I never met you in a moment of high inspiration. There must be a word for the feeling you awaken in me, that tender astonishment in beauty suddenly revealed, as if from beneath a rock rolled away by unseen hands. Come to think of it, I know the word. The word is love.

Forever your friend,

Rona

Now over to you. I can’t wait to see what you have to say—about conversations you wish you could have, dating someone gay, learning from literature or anything else..

You have far more bravery than I can muster at present. I was born in a large city, but my father wanted property and moved us to the country when I was in 3rd grade. We were 25 miles from the catholic high school. I commuted there by school bus daily for 4 years, but never dated because of the distance (to date me was 25 miles to pick me up, 25 miles to the action, 25 miles to take me home, then 25 miles for the guy to get home). I went off to college completely ignorant of any relationship information. My parents didn't discuss sex in any form. I met a guy I liked and we went on three dates. He was sweet and funny, but suddenly stopped calling, I went to his dorm and was informed by his roomie that "Chuck had attempted suicide and was hospitalized. Didn't I know he was gay and conflicted about his feelings for me?" I had no idea. I didn't even know what gay meant. I never saw or heard from him again. I met and fell in love with another college guy. He was smart, literate, funny and we hit it off and dated for a year. When he told me he was ending our relationship because he was gay, it practically ripped out my soul. In hindsight, it was a defining moment that altered the direction of my life in ways too numerous to list here. It also tainted every encounter I had with every guy I met for a very long time. They would ask me out, I would ask if they were gay. They would walk away. I don't know if that was because they were gay, or because I had insulted their fragile male ego and their masculinity by asking such a thing. I just didn't want to be hurt again. I have now been married to a wonderful man for 50 years. In that time I have met and befriended many gay men at work and in life. I just wish that our society could have accepted them for who they were back when they were young, so they could have led less painful lives, not dating and marrying women to fulfill parental expectations, and then eventually leaving heartbroken spouses and children in the aftermath. Everyone deserves to live the life they were meant to live. No one benefits when people feel forced into living in ways other than being their authentic selves and loving who they were meant to love.

I'm sure that this beautifully written tribute to your one-time 'boyfriend', together with the complex mixture of emotions that almost everyone must have regarding their adolescent selves, will resonate with many a reader. I wonder what is in the air that both you and David went down the same rabbit hole. I, too, went out with quite a few unsuitable boys/men before I found the right one over sixty years ago.

Incidentally, decades later, I became very close to two very different gay men, both now dead but only one from AIDS and ended up writing a book about people with AIDS. Published in 1992, when it was absolutely a killer disease, it is very poignant (Ian McKellen wrote a Foreword and said it was "as powerful as any great classic of fiction") because it tells their stories in their own words and they were dealing with stigma, prejudice and the knowledge that they were facing an early death. Rarely bought these days because it is only of historical interest, if you're curious, see Wise Before their Time by me.