Voice Lessons from a Literary Warrior

Before I dared tell a story of my own, Tillie Olsen planted the seed of my courage.

Old friends may remember this one, first published more than a year ago and still a personal favorite. I’m seizing my last chance to celebrate Women’s History Month. If you’ve ever longed to speak in your own voice and wondered how to begin, Tillie Olsen is your kind of mentor.

“Look at that front row,” said my mother. I’d been trying not to stare at the three queens of fiction. Both Margarets, Atwood and Laurence, sharing a private joke. Alice Munro on the edge of her folding chair—elbows on knees, face alight. A hush fell on the room as Tillie Olsen took the podium. She had published only three books. None long, all revered for the oracular power she brought to her unifying theme, the fierce love of the underpaid and overlooked for something greater than themselves—a family, a cause, a work of art.

Olsen didn’t look like my notion of a literary star. Then in her late 60s, she must have thrown on whatever was clean and near at hand before styling her thick gray hair with a scrunch of the fingers. Her compact frame bristled with energy, as if at any minute she might be called away to hold the hand of a bereaved friend or rally the troops for a protest. As a champion of far-left causes, she’d done a lot more than march. She’d been arrested and jailed.

The book in her hands that April night in Toronto must have been Silences, her thunderclap of an essay on the forces that stop creators from creating. Wrong class, wrong color, wrong gender. Olsen had the good fortune to be white, the daughter of Jewish immigrants, but she’d been schooled hard on class and gender. When she landed a contract with Random House for a novel begun in her teens, her future glowed with promise. Then she put the novel on hold to raise four children and bring home a paycheck any way she could as a high-school dropout. She trimmed meat, slung hash. The world’s rough edges burnished her. What she saw, she knew. And after long silence she told it.

That night at the reading in Toronto, I arrived directly from the office in my good jacket and a silk shirt found on a sale rack. My purse held a complimentary copy of Silences. Free books were a perk of my first job at Miss Chatelaine, a former teen magazine on the path to reinvention as the fashion magazine known as Flare. Since the magazine would not be reviewing Silences, I hadn’t read past chapter one. I admired Olsen for the soulful rigor of her short stories, which read as if carved from granite, word by word, in stolen moments.

The story that won my heart, “I Stand Here Ironing,” is a working-class mother’s meditation on a daughter raised in hard circumstances. Equal parts love song, lament and battle cry, it pulses with the mother’s pride in doing the best she could. I took the last lines personally: “Let her be. So all that is in her will not bloom—but in how many does it? There is still enough left to live by. Only help her to believe—help make it so there is cause for her to believe that she is more than this dress on the ironing board, helpless before the iron.”

When would I bloom? Never mind all that was in me; a little would do.

A vague yearning to to write as myself could not withstand my fear of nothing to say.

Compared to Olsen at my age and stage, I had it easy. At work I had fun with madcap colleagues and won respect for whipping copy into shape on deadline. My own prose clicked along like stilettos on a dance floor: “If sheer hard work and thoroughness could clinch an executive title, you’d see fewer women pounding a typewriter and more making a case in the boardroom.” In the magazine’s best-pal voice, I turned out book reviews, travel tips and peppy motivational essays. A vague yearning to write as myself could not withstand my fear of nothing to say. What did I know about the world beyond the sturdy brick starter house where my husband and I raised our son and argued about who did what around the place?

My mother, a widely published journalist and author, had groomed me for a writing career. She took a red pen to all my entries in the contests I won in high school, placed a short story of mine in a national magazine. In her effort to ease my way to a book deal, she rattled my faith that I could write one honest line not in need of her edits. Doubt settled upon doubt like layers of soil upon a tomb. At the office, I shone. Writers feared me, and I liked it that way. My future looked clear: a better-paying job at a bigger magazine.

Let me be.

To score an invitation to the party in Tillie Olsen’s honor, you had to be one of three things: author, literary gatekeeper or Fredelle Maynard’s daughter. My mother flirted and teased her way through the crowd, her silver earrings flashing. Glasses clinked; the buzz of shop-talk verged on a roar. A legendary drinker spilled his whisky, a drenching that silenced the room until the jester of the tribe made a timely quip. What was I doing in this crowd, a nobody who edited makeup tips?

I staked out a corner of the couch, hoping no one saw me. Someone did. Sat down beside me. Without a word, took my hand.

Tillie Olsen.

The party swirled before us as Tillie’s warm right hand rested on mine. The hand that cut, that stirred, that consoled, that wrote. Why me? Perhaps she looked for the outsider at every literary party—the young woman silently asking when a little of her would bloom. Tillie had raised four daughters; I was 30, a daughterly age. I like to think she was looking for someone whose belief she could kindle—someone she could not disappoint as every mother disappoints her child to some degree. I was hungry to believe. Could she please sign my copy of Silences?

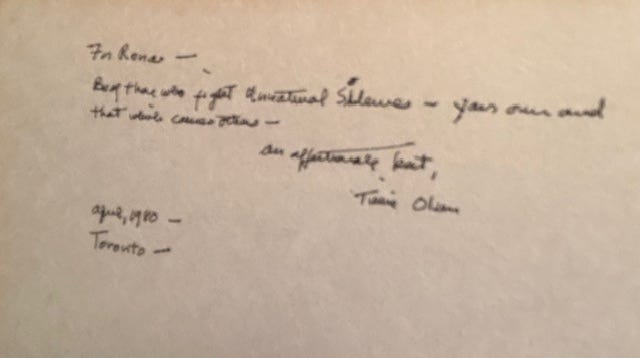

She had the tiniest penmanship, fit for a doll’s book.

For Rona—

Be of those who fight unnatural silences—your own and that which causes others—

An affectionate pat,

Tillie Olsen

April, 1980—

Toronto—

I spent another 24 years in the safe harbor of the magazine business, rising to the top job at Canada’s leading women’s title. My mother didn’t live to see the day. As she lay dying of a brain tumor, unable to speak, I told her I wanted the position, which would not be open for another five years. I was holding her soft hand. The hand that held the red pen, that stirred the soup, that checked my brow for fever. Now the hand moved only when a nurse applied lotion. As I stroked the place where my mother’s watch had been, I felt the slightest pressure on my palm. My mother, squeezing my hand.

What I loved best about the job was writing my editor’s column, in which I told stories I had lived. Readers used to say they turned to it first or saved it for last, like the most luscious chocolate in the box. But I didn’t think of myself as a writer. From time to time, I’d pull Silences off the shelf and reread Tillie’s call to arms with a flutter of unease.

Not every revolution strikes at a foe. For a woman who writes, the first barricade is within. To claim what you know, and tell it in your own voice, is a revolutionary act that not only remaps your emotional world but clears a path for others. That’s what I’d begun to do in my editor’s column. If my joys, sorrows and amusements mattered, then so did my reader’s.

For a woman who writes, the first barricade is within.

Every story begins with the unwritten words, “Listen up. This matters.” The story won’t be told unless it matters every bit as much as folding laundry, cooking pot roast or cutting a hundred grand from the budget. I had to leave my job to write my first book, and would have put it on hold in a flash if anyone had said, “We need you to launch a magazine.”

What did I know? I knew how to run a magazine. Rattling around in the empty box of a day, I heard three sentences. They came to me as if dictated from within: “My mother gave birth to me twice. The first time is a matter of record. The second, almost forty years later, took place at her deathbed…”

My mother died at 67, just before I turned 40. She cast a mighty shadow, where I might have remained had she lived—neither a writer nor a first-rank editor. I loved her boundlessly, and yet her death opened a door. It took courage to say that I flourished without her. I knew what I knew and told the story. I called the book My Mother’s Daughter.

I’d love to know what this post sparks in you—about Tillie Olsen, finding your voice, mothers and daughters or anything else. There’s no predicting where you’ll take our discussion, and that’s the way I like it. When the thread starts to hop, I can be a bit slow to answer comments. I’ll get to yours, though. Every comment matters.

All my posts are free to read and share. Got a friend who needs some Tillie Olsen in her life? Click the red button. I’m looking for readers attuned to the art of amazement—not simply more readers, but the right readers. A tribe who find courage in stories that nourish conversation.

A few generous members of the tribe have chosen to pay for their subscription. If you feel moved to join them, you have my joy and gratitude.

P.S. If my mother were alive today, she’d have thousands of readers on Substack. What a force she was. You can meet her here, introducing a rapt group of adult learners to Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.”

Well, my mouth is hanging open. I know, not the loveliest image to conjure, but this one made me weep. First, I love/d Tillie Olson with everything I have. I haven't read "I Stand Here Ironing" in years, will reread today. And of course, "For a woman who writes, the first barricade is within."

I started late, as you know, and am so grateful that I finally dropped the barricade and decided it was time to shine. My parents both held me back, I'm sure not for the same reason or involving similar dynamics that you experienced with your mom, but I too, needed my dad to die for my true life to begin. It was the oddest blessing I've ever received. Go, live, be. Love to you, my dear and supremely talented friend! xo

“To claim what you know, and tell it in your own voice, is a revolutionary act that not only remaps your emotional world but clears a path for others.”

Don’t be surprised if I adopt your words as a personal Mission Statement! So eloquently you remind all of us to get ‘what’s in there, out’ not only for the benefit of others, but also for our own emotional health. Thank you!