Voice Lesson from a Literary Warrior

Before I dared tell a story of my own, Tillie Olsen planted the seed of my courage.

“Look at that front row,” said my mother. I’d been trying not to stare at the three queens of fiction. Both Margarets, Atwood and Laurence, sharing a private joke. Alice Munro on the edge of her folding chair—elbows on knees, face alight. A hush fell on the room as Tillie Olsen took the podium. She had published only three books. None long, all revered for the oracular power she brought to her unifying theme, the fierce love of the underpaid and overlooked for something greater than themselves—a family, a cause, a work of art.

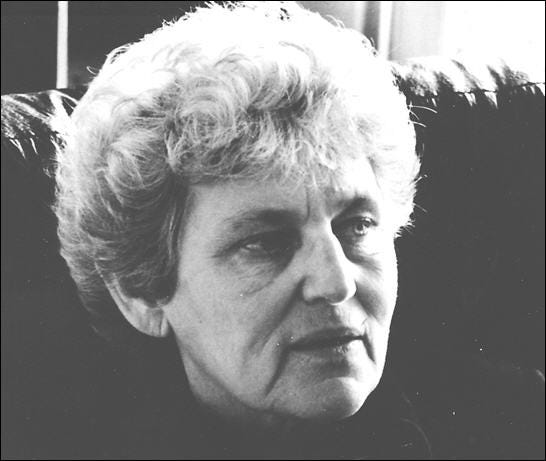

Olsen didn’t look like my notion of a literary star. Then in her late 60s, she must have thrown on whatever was clean and near at hand before styling her thick gray hair with a scrunch of the fingers. Her compact frame bristled with energy, as if at any minute she might be called away to hold the hand of a bereaved friend or rally the troops for a protest. As a champion of far-left causes, she’d done a lot more than march. She’d been arrested and jailed.

The book in her hands that April night in Toronto must have been Silences, her thunderclap of an essay on the forces that stop creators from creating. Wrong class, wrong color, wrong gender. Olsen had the good fortune to be white, the daughter of Jewish immigrants, but she’d been schooled hard on class and gender. When she landed a contract with Random House for a novel begun in her teens, her future glowed with promise. Then she put the novel on hold to raise four children and bring home a paycheck any way she could as a high-school dropout. She trimmed meat, slung hash. The world’s rough edges burnished her. What she saw, she knew. And after long silence she told it.

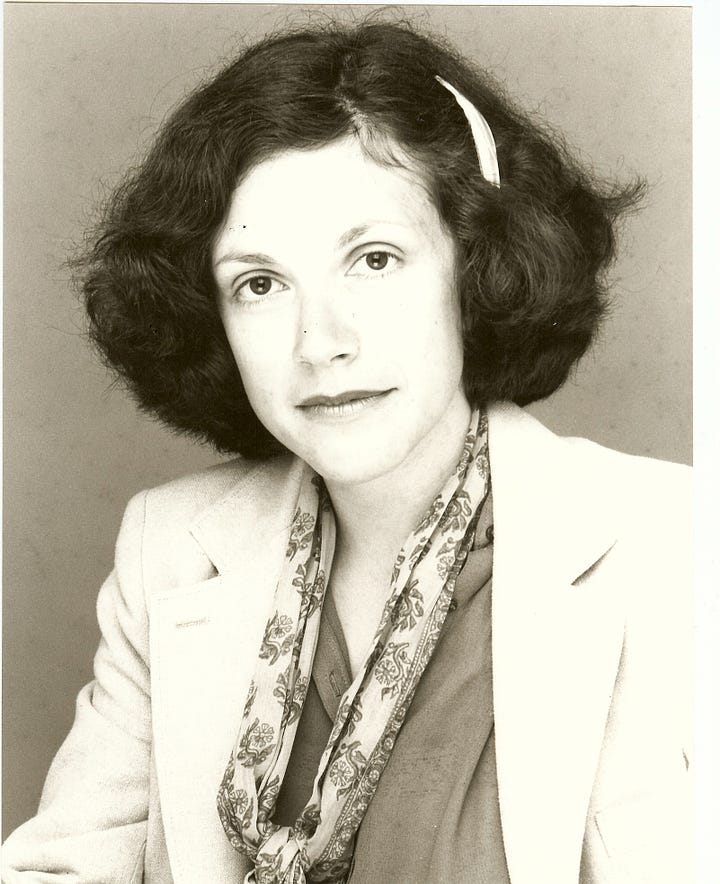

That night at the reading in Toronto, I arrived directly from the office in my good jacket and a silk shirt found on a sale rack. My purse held a complimentary copy of Silences. Free books were a perk of my first job at Miss Chatelaine, a former teen magazine on the path to reinvention as the fashion magazine known as Flare. Since the magazine would not be reviewing Silences, I hadn’t read past chapter one. I admired Olsen for the soulful rigor of her short stories, which read as if carved from granite, word by word, in stolen moments.

The story that won my heart, “I Stand Here Ironing,” is a working-class mother’s meditation on a daughter raised in hard circumstances. Equal parts love song, lament and battle cry, it pulses with the mother’s pride in doing the best she could. I took the last lines personally: “Let her be. So all that is in her will not bloom—but in how many does it? There is still enough left to live by. Only help her to believe—help make it so there is cause for her to believe that she is more than this dress on the ironing board, helpless before the iron.”

When would I bloom? Never mind all that was in me; a little would do.

A vague yearning to to write as myself could not withstand my fear of nothing to say.

Compared to Olsen at my age and stage, I had it easy. At work I had fun with madcap colleagues and won respect for whipping copy into shape on deadline. My own prose clicked along like stilettos on a dance floor: “If sheer hard work and thoroughness could clinch an executive title, you’d see fewer women pounding a typewriter and more making a case in the boardroom.” In the magazine’s best-pal voice, I turned out book reviews, travel tips and peppy motivational essays. A vague yearning to write as myself could not withstand my fear of nothing to say. What did I know about the world beyond the sturdy brick starter house where my husband and I raised our son and argued about who did what around the place?

My mother, a widely published journalist and author, had groomed me for a writing career. She took a red pen to all my entries in the contests I won in high school, placed a short story of mine in a national magazine. In her effort to ease my way to a book deal, she rattled my faith that I could write one honest line not in need of her edits. Doubt settled upon doubt like layers of soil upon a tomb. At the office, I shone. Writers feared me, and I liked it that way. My future looked clear: a better-paying job at a bigger magazine.

Let me be.

To score an invitation to the party in Tillie Olsen’s honor, you had to be one of three things: author, literary gatekeeper or Fredelle Maynard’s daughter. My mother flirted and teased her way through the crowd, her silver earrings flashing. Glasses clinked; the buzz of shop-talk verged on a roar. A legendary drinker spilled his whisky, a drenching that silenced the room until the jester of the tribe made a timely quip. What was I doing in this crowd, a nobody who edited makeup tips?

I staked out a corner of the couch, hoping no one saw me. Someone did. Sat down beside me. Without a word, took my hand.

Tillie Olsen.

The party swirled before us as Tillie’s warm right hand rested on mine. The hand that cut, that stirred, that consoled, that wrote. Why me? Perhaps she looked for the outsider at every literary party—the young woman silently asking when a little of her would bloom. Tillie had raised four daughters; I was 30, a daughterly age. I like to think she was looking for someone whose belief she could kindle—someone she could not disappoint as every mother disappoints her child to some degree. I was hungry to believe. Could she please sign my copy of Silences?

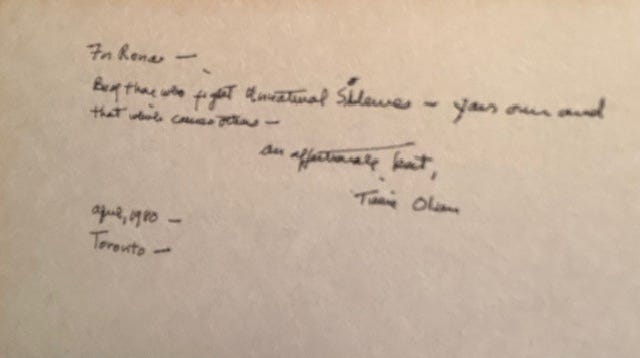

She had the tiniest penmanship, fit for a doll’s book.

For Rona—

Be of those who fight unnatural silences—your own and that which causes others—

An affectionate pat,

Tillie Olsen

April, 1980—

Toronto—

I spent another 24 years in the safe harbor of the magazine business, rising to the top job at Canada’s leading women’s title. My mother didn’t live to see the day. As she lay dying of a brain tumor, unable to speak, I told her I wanted the position, which would not be open for another five years. I was holding her soft hand. The hand that held the red pen, that stirred the soup, that checked my brow for fever. She squeezed my hand.

What I loved best about the job was writing my editor’s column, in which I told stories I had lived. Readers used to say they turned to it first or saved it for last, like the most luscious chocolate in the box. But I didn’t think of myself as a writer. From time to time, I’d pull Silences off the shelf and reread Tillie’s call to arms with a flutter of unease.

Not every revolution strikes at a foe. For a woman who writes, the first barricade is within. To claim what you know, and tell it in your own voice, is a revolutionary act that not only remaps your emotional world but clears a path for others. That’s what I’d begun to do in my editor’s column. If my joys, sorrows and amusements mattered, then so did my reader’s.

Every story begins with the unwritten words, “Listen up. This matters.” The story won’t be told unless it matters every bit as much as folding laundry, cooking pot roast or cutting a hundred grand from the budget. I had to leave my job to write my first book, and would have put it on hold in a flash if anyone had said, “We need you to launch a magazine.”

What did I know? I knew how to run a magazine. Rattling around in the empty box of a day, I heard three sentences. They came to me as if dictated from within: “My mother gave birth to me twice. The first time is a matter of record. The second, almost forty years later, took place at her deathbed…”

My mother died at 67, just before I turned 40. She cast a mighty shadow, where I might have remained had she lived—neither a writer nor a first-rank editor. I loved her boundlessly, and yet her death opened a door. It took courage to say that I flourished without her. I knew what I knew and told the story. I called the book My Mother’s Daughter.

Whether you’re a regular here or stopping by for the first time, I’d love to know what this post sparks in you—about Tillie Olsen, mothers and daughters or anything else. Paid subscribers to may remember several long and rich discussions of “I Stand Here Ironing” (dive back in here). And before I forget, I’m overdue to thank four readers who have pledged their support to Amazement Seeker—Debby Waldman, Kimberlee Jones, Judy Farrant and Chris Bell. You kindle my belief.

Good morning Rona. We both belong to the kinship of the exacting mothers of the red pen. How I dreaded every school project, wherein she would insert her demanding self. The fault finder. I was uncertain I could manage the smallest of things on my own, when I escaped the house at age 17. At UC Berkeley I felt like an imposter. I had hand carried my transcript over at the last minute, having been pushed into Whitman, where I had threatened to major in skiing.

Recovery from feelings of inadequacy is a slow torment. I still lament lacking the courage to submit work for consideration in a class led by Lillian Hellman. At the end of the quarter, I like you was there at a party given in her honor. She held court in the small room with tales of Dash Hammett. I loved her for having the courage to not marry. When I said goodbye to her at the end of the party, faltering as I explained I had not submitted anything, she did for me what Tillie did for you. She took my hand. She told me never to let my doubts stop me again. “You are a fine writer,” she told me. I wondered only a fraction of a second how she could possibly know, then as you might reach for the brass ring from the merry-go-round, I seized her words and took them into the bottom of that place inside where our own words grow. I had been given nourishment.

Wow. Yes. I, too, had a very powerful professional mother, but her method wasn't to correct me, but to diminish me directly. I had a super-clever(Asperger's?) older brother and a super clever younger sister (published in the Atlantic magazine in her twenties, but then died in a car crash) and my mother said to me, when I was in my teens, "It's perfectly ok to become a home-maker". So I never knew I was clever until years and years later, despite doing well in school etc etc. In other words, I didn't have a Tillie Olsen in my life. When my mother eventually got Alzheimer's, it's a terrible thing to say, but I felt relieved, I said she was 'de-clawed'. My saving grace was my father, who did believe in me but probably didn't say so enough.