Three's a Crowd

Friendship expands the heart of a child. When it's over, love needs somewhere to go.

My little sister had been looking for a friend when she spotted the twins from the back seat of our old Buick. Pink rompers, pink ribbons on their shiny pigtails. The perfect age, around six. They straddled a jungle gym in a yard that only yesterday was nothing but dandelions and crabgrass. Twoness made them exotic, like children from a faraway country Joyce and I could only imagine, where horses flew and sorcerers cast spells. My sister’s eyes grew wide with longing.

At 10, I’d never heard of a coup de foudre. But that’s what I had witnessed, a thunderbolt to the heart.

Until that moment, I’d have told you Joyce had everything she wanted. It looked that way to me, the big sister she outshone in sweetness and adorability. She got a pass for roughing up my dolls (“Rona, try to be kind to your sister. She admires you so”). She got the cookie with the most chocolate chips (I counted). Night after night, she got chicken wings fried to order because she would eat nothing else. “It’s no trouble,” said our mother, between mixing dream bars, seasoning the London broil and hunting for Daddy’s glove.

Anything for Joyce. Would she never get a comeuppance?

King Arthur vowed to find the Holy Grail. Jason went in search of the golden fleece. Our mother promised Joyce the twins. If anyone had magic powers, it was Fredelle Maynard. She turned pop bottle caps plates that held real golden pies for dolls, a trunkful of oddments from an auction into my prizewinning Halloween costume (Little Bo Peep, with bonnet and crook). But I was not at all sure she could conjure friendship. From what I’d seen, kids enchant each other. The spell might not last; I’d seen that too. And I couldn’t wish it on my sister.

Once upon a time, I was chosen above all others by the loveliest child in kindergarten. Robbie had a crown of silky curls, a serious gaze and a limp—a souvenir of polio—that made me want to look out for him. I glowed when he brought his doll to school and announced that her name was Rona. We were going to get married one day.

My mother’s only role in this bond was chauffeur. I needed a ride to the farm where Robbie lived. In the woods behind his house, he blazed a trail to our special place, the fallen tree we called our pirate ship. Robbie played Captain Hook to my Wendy (we were both mad for Disney’s Peter Pan). As I walked the plank, he held my hand all the way. He knew I was afraid of stumbling.

No word but love embraces what we shared—what all kids share with the chosen friend who chooses them back. At home parents lay down the law; friendship is its own kingdom, a refuge and a rapture. You create it in tandem, one adventure at a time. Together, you practice every note on the emotional scale. Grownups call you playmates, missing the totality of who you are side by side—protectors, confidantes, mischief makers, mirrors of your true emerging selves. If it ends too soon, they don’t see your pain.

In first grade Robbie dropped me to find his place among the boys. He apparently forgot that he ever had a doll named Rona. At recess he tagged after his new pals while I told stories to myself on the edge of the playground. Instead of friends, I had a whole cast of characters, from rampaging dragons to pining princesses. I’d grown accustomed to the taunts of other kids. It’s not as if they they’d ever been my friends. But when Robbie joined in, I flinched as if he’d struck me.

Boys will be boys, my mother said. Nothing personal.

It didn’t take Fredelle Maynard long to find the mother shepherding our town’s only twins. Penny and Pammy McClure did not simply enter a swimming pool, a grocery aisle or wherever it was that my mother sealed the first play date. Any place they went became a stage for their bubbling, gesticulating twoness. Their mother, Evie, ran after them with a flyaway bun and an air of proud frazzlement. Joyce’s longing to meet her twins confirmed what she had always known: the unsurpassable distinction of Penny and Pammy. Yes, she’d be delighted to bring them by.

Evie McClure drove the only MG in town, dandelion-yellow. When the twins hopped out in our driveway and burst through the door, it seemed the circus had arrived. They proceeded to make merry with the dress-up box, the colored pencils in every hue and the hand-sewn cushions that were not supposed to leave the Danish sofa. They shared Joyce’s zest for turning nothing into something—a skit, a cartoon, a poem. They had all her brio, times two. Unlike Joyce’s other playmates, they wouldn’t let her lead the games. They had to outshine her and each other. My little sister, the center of attention since birth, was in awe.

So it began.

Joyce must have played at the McClures’ from time to time, but the little house they rented was no match for ours, with its broad staircase for theatrical productions and cornucopia of craft supplies. As Joyce’s friends, the twins had access to the dollhouse with its miniature tea set, the collection of Steiff bears and bunnies in wardrobes sewn by our mother. They reminded me uneasily of Joyce, those big-eyed critters. Too winsome for this world. Penny and Pammy had no use for soft, winsome things. They wanted to dazzle, not to tuck Teddies under crocheted blankets.

Evie couldn’t whisk the twins away without a full report on their latest achievements. Writing had to be declaimed, art applauded. “Pammy Picasso!” Evie once cried, brandishing a picture that would look just fine on her fridge. A sly smile crossed Pammy’s face. She knew she had beaten her sister. Mine too.

There wasn’t any other child the twins preferred to Joyce, but other children didn’t interest them. Twoness gave them everything they needed. Joyce and I were buttering our toast one morning when she told me she’d just dreamed about a ride with the twins in the yellow MG. They were having the jolliest time until the door flew open, pitching Joyce onto the road while Evie trilled over her shoulder, “What’s that you said, Joyce?” My little sister, who showed me up just by existing, did not need pen, paper or competitors to tell a story that made me ache for her.

The McClures didn’t stay long in our town, maybe two or three years. By the time they pulled up their stakes for Arizona, our mother had soured on the family. Evie, she declared, was a shill for two spoiled brats whose vaunted gifts came nowhere close to Joyce’s. They didn’t deserve her friendship, hadn’t even bothered with a proper goodbye. So I was the one who walked Joyce over to the little white house with the peeling paint, vacated just hours ago. She missed Penny and Pammy already.

The McClures hadn’t bothered to lock the place or even take a broom to it. We wrinkled our noses: something had spoiled. In the twins’ old bedroom, we found scuff marks on the walls and broken toys at our feet. Orphaned puzzle pieces, headless dolls. What a bunch of slobs. Joyce wouldn’t say a word against the McClures, but someone had to.

When Joyce set her heart on the twins, she didn’t know about unrequited friendship. I had known since first grade. From my story corner at edge of the playground, I’d watch Robbie scramble after the boys, bumpity-bump with his polio gait. He would never catch up or stop trying. And I loved him for that, even though he no longer loved me.

The stories I dreamed up at recess would be written, illustrated and praised by my mother, their best lines quoted in letters to her own mother. My dragons and princesses came from the Brothers Grimm, but meanwhile the real story was writing me—one I wouldn’t see for a lifetime, much less tell. I had lost Robbie but the story wasn’t over. The love he left behind needed somewhere to go.

My sister has forgotten her first glimpse of the twins and her last visit to the room that was theirs. I’m the one who replays it to this day. Dust motes quiver in the air as Joyce’s eyes mist over. A different big sister would take her hand, but we both know I’m not that kind. What I can do is witness her sorrow. The child alone on the playground stands beside the dream child thrown from Evie’s disappearing MG. For a moment they are one and the same.

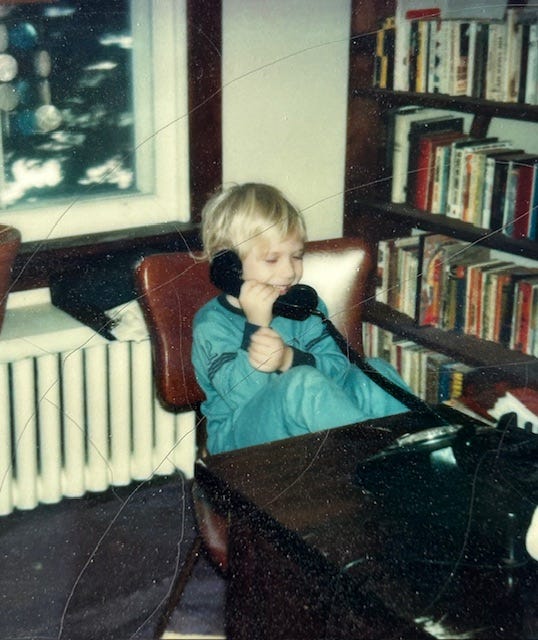

Has a childhood friendship shaped your life? Let’s talk about it—or your child’s foundational friendship, if you prefer. To inspire you, here’s my son Ben, age five, on the phone to his inseparable friend Damian. I’ll do my best to answer every comment, but this time I’ll be responding from Spain. Please bear with me.

Friendship is a favorite theme of mine. If this essay touched you, head over to one of my most popular posts yet, “How to Be a Friend.”

There’s always more for a writer to discover in any story worth telling. Today’s essay began with a very different focus: sibling rivalry. Curious? Have a read.

I welcome paid subscriptions. Okay, I don’t just welcome these flashes of gladness. Every one makes me smile. Remember, though, you have other ways to build this community. Click the heart, leave a comment, share a post. It’s all free to read. Because, without readers, where would writers be?

Robbie had a doll named Rona. That killed me. The sweetest. I adore this essay.

I had trouble making friends when my family moved from Manhattan to Long Island when I was 7. Before that time, I had friends, one special one named Vicki, and yet, I don't have any stand-out memories. When I was in 7th grade I found my bestie. We'd traveled through elementary school together, were in a Brownies troop together, but weren't really drawn to one another until later. And when our friendship happened my life was good. I was head over heels in love with Susie, as a friend, not a romantic interest. And then, just like that, in 8th grade, she stopped talking to me. For an entire school year. I was utterly confused and heartbroken, and she wouldn't explain why she'd left our friendship. I was completely shut out. By ninth grade, she returned, and filled with shame, admitted to me that there were people who were gossiping, saying we were lesbians. I barely knew what that was at the time. She decided it would be easier to walk away than defend something that meant so much to her, too. We mended the hurt (somewhat), and reunited. Once, when she was in college, and I was out in the world, working, she came to stay with me, and we shared a bed for that night. We ambled around in bed, and tried kissing. One kiss, and we pulled away, looking at each other, and burst out laughing. We were never that kind of couple.

And the separation still brings pangs of hurt when I think about it.

I spent much of my life— decades now numbering seven— longing for a different kind of sister— a sister who’d call me up on a regular basis just to share small details of our lives, a sister with whom I’d go shopping, take a trip to the beach , consult on children, my crumbling marriage, work projects, the stuff of daily life.

When we’d pay each visits — not just every year or five. When our father got drunk— as he did every night of our childhood—and when our mother was dying , we’d find solace in each other’s arms.

That never happened, and I understand why. As wildly as our mother loved us both , and as much as we returned her love, she pitted us against each other in a manner I never replicated with my own children.

It has taken us most of seventy years to find our way back to each other. It is my sister’s writing about us, and about our family, that accomplished this. Not Sunday night phone conversations or trips to the nail salon together. It’s quiet moments like this one in which we find ourselves a thousand miles apart, when I open up an essay she has written and feel the love and connection in her words.

And a rush of love for my sister overcomes me.

Rona, you have given and continue to offer one of the greatest gifts one person can provide to another: the gift of being seen, remembered, known.

Even when I don’t remember the details of my story, I can count on my sister to do so.

With love.