This Old Bone House

The body I sculpted at the gym has become a fixer-upper, but it's never been more dear to me.

Herkimer the skeleton dangled from a hook in Mrs. Milliken’s ninth-grade science classroom. If she thought his jaunty name would get us pumped for the anatomy unit, she thought wrong. Herkimer gave me the creeps. He was the Halloween ghoul inside me, awaiting his moment for the Big Boo. No matter what became of the zit on my nose or who deigned to sit with me at lunch, Herkimer would one day expose the real me: a lipless grin, a heap of bones.

My body was not my friend. I didn’t know it anymore. It sprouted hair in unfamiliar places, bled onto the back of my skirt and made me wear the badge of shame down the corridor. I wanted a more pleasing fleshly container for the dreams that pulsed in my head. A fourteen-year-old body is nobody’s friend. Breasts jiggle or haven’t had the grace to show up. The penis develops a mind of its own. In that classroom we all dangled from the hook of bodily embarrassment.

Mrs. Milliken was tied with her husband, who taught Latin, for most beloved teacher in our school. Unconcerned with beauty or fashion, she let her hair frizz and her stomach bulge, a rare liberty in the heyday of girdles. She radiated tender bemusement at our foibles. When some wag asked her, “What’s the dirtiest part of your body?”, we chortled and smirked. Mrs. Milliken would never say, “Butt hole.” She’d use the correct anatomical term. Until she did, we thrilled to the unspeakable truth.

A young body is like a solid house with all the hot water you could want and a roof that keeps out the rain.

All questions mattered to Mrs. Milliken. “The mouth,” she said, as if she’d just been asked the number of bones in a body. I was not among those who were already French-kissing, and telling the tale at slumber parties. After the French kiss, forbidden pleasures happened "down there." No boy had ever kissed me. Would my turn ever come? Yes, the mouth sounded right.

What fine bodies we had then, even gym-class failures like me. We walked as long and as far as we desired. We stooped, reached and jumped out of chairs to run for the phone, which could only be for us. Rolled on the grass, then rose to our feet in a fluid motion. Slept the luxuriant sleep of the exhausted.

A healthy young body is like a solid house with all the hot water you could want and a roof that keeps out the rain. Still, you dream of trading up. All summer at the town swimming pool, other girls lay Coppertoned and glowing on beach towels, their beauty a needle in my heart. I wanted those taut bellies, those legs that went on and on.

At 30-something I tried on a swimsuit and recoiled. So began a creative obsession: thighs that did not quiver, a midsection that knew its place, upper arms that begged to be flaunted. I joined the Y and made it happen. I was furiously cycling to nowhere on a stationary bike, resplendent in turquoise Lycra, when a staffer came by, all smiles, after showing a newbie around. “She pointed to you, and said, ‘I want to look like her.’”

Take that, Coppertone girls.

I’d worked for this new body of mine, and I vowed to keep it forever. Why not? Six days a week I pumped, pulled and pressed. No wonder former generations crumpled—they weren’t in on the secret.

“You don’t look 67,” people told me, as if looks were the issue. One October afternoon, when skeletons hung from trees and plastic gravestones rose from fallen leaves, my dog and I rounded a corner and were ambushed by a giant ghost, waving its inflatable arms. Casey reared up to defend us, I went flying. I lay facedown on the sidewalk, leash tangled around one leg. There I remained, both knees throbbing with pain, until a couple of gray-haired Samaritans helped me to my feet. They looked at me with dismay, as if I’d been fool enough to attempt a backside ollie on a skateboard. “Strong dog you’ve got there,” said one (meaning: too strong for someone our age).

My body, renovated and buffed at the gym, had become a fixer-upper. It sputtered, it creaked, it would recapture no more than a jot of its old glory. I hardly knew the place.

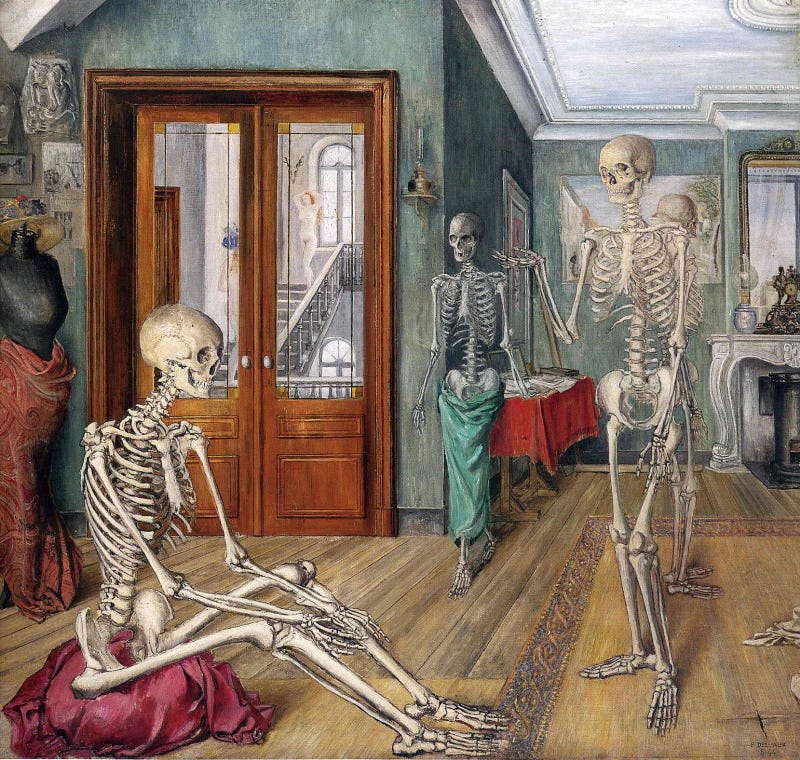

More than half a century ago, when my body carried me from party to party on a wave of intoxicants, I studied the first poets in our language. The people they consoled and entertained led short lives under constant threat of death. They sailed into the unknown on “the whale road,” braved “the shield wall” to fight invaders. Of all their pithy coinages, my favorite was what they called the body: “bone house.” Those anonymous poets told the truth about where we all live and what we’ll leave behind.

Let’s take a quick tour of my bone house. Crooked spine that used to hold me up without complaint, but now gives me hell if I reach too quickly for a towel. Both feet knotted with lumps and bumps, like old trees. My father, who had the same feet, spent his last years in a wheelchair. When pain gets the better of me, I ask myself, "How much worse will this get?" At least it’s not Parkinson’s or cancer. My grandmother’s voice rings in my head, her Yiddish tangy as her sweet and sour meatballs: “An ergeneh zach zoll nisht trefen.” May this be the worst thing that happens to you.

I savored those moments when my feet pushed off with ease against the ground.

Walking Casey taught me everything I know about the joy of movement. He joined the family as a frisky adolescent, and beside him I was blithe for the first time in memory. I savored those moments when my feet pushed off with ease against the ground and my hips rolled me forward as they did before I recognized the marvel of the quietly compliant body. The leash swayed; a starling rode the air on a fury of wingbeats. The oldest maple in the neighborhood spread its canopy. Blight dotted the leaves, yet from a distance all I saw was green. I could have sworn this patch of ground had been waiting for my footsteps, or maybe it was my footsteps that had waited to arrive precisely there. The absence of pain shocked me into gratitude. Why bother working out at the gym, when every dog walk was play?

I don’t recall when it struck me that we were slowing down. Medication kept Casey’s arthritis in check, but there was no stopping his cancer. Toward the end he hardly walked at all. His ashes came home in three layers of midnight blue, like a gift from a temple of fashion—glossy paper bag, velvet sack, cardboard scattering tube. I shook a handful of ashes into my palm. My mother’s contained bone fragments. My dog’s resembled sand from a beach.

How long had it been since I moved?

If I burn it and skip the scenic route, I can walk to the Y in 12 minutes. Then I stride around the track for a while. Better not push my luck, or my knees will whine like geezers vying for the pity prize. I’m overdue for a strength routine.

No one notices a septuagenarian in pilled tights and black Hokas that would suit an old-school nun. Round and round I go in the weekday morning bodyscape. A pigtailed kid twirls as her dad chugged away on the step machine. Someone mounts the treadmill with such grace, I hardly notice one leg is made of metal. A classroom full of women, none sylph-like or much under 50, reach for the ceiling as if for a handful of stars.

This time next year, some of us will be sporting new moves and the silhouettes to match. Some will be taking it easy while an injury heals, and some will be gone forever. I don’t look 75, I’m told. But my next medical test could be the one that condemns this old bone house, which still gets me from here to there despite some grumbling on the way. I know the place, quirks and all. It’s home.

Your turn now, my friends. How do you like your one and only bone house? Have you come to terms with a body that’s now the youngest it will ever be, or do you still aspire to a leaner, stronger model? If movement is a pleasure rather than a duty, how do you keep it that way? I always learn a thing or two from this group.

Trust an old dame to have lots to say about aging. Here’s my take on the joy of letting yourself go. Teeth that crumble like Victorian chimneys are another story—expensive but good for some laughs.

My posts are free to read, yet some readers of heart and means are paying for subscriptions just because. If you are so moved, I’d be incredibly grateful. No pressure, though. I’m here to meet a community of readers, and you are all among the great joys of my life. Feel free to share—you’ll be spreading the word about Amazement Seeker.

At seventy-three, oh, how I relate to this! I've never liked my hands. After years in the sun, they prematurely wrinkled. They have embarrassed me more than once. But still, when I was in my forties I relentlessly pushed myself at the gym until I had that sculpted body I was proud of. After sustaining a fall down some stairs that broke my neck at 49 and then other serious medical issues, I have problems just getting around on two feet (also arthritic in my feet). I watch children and young able-bodied adults and reminisce. One day, I looked at my hands and noticed how elderly they looked. I felt an unusual feeling of gratitude and love. "Thank you hands," I said. "Thank you for taking care of me all these years. You've been faithful." They no longer seemed ugly.

At the risk of overstaying my welcome, let me tell you one story.

When my son was five years. old, he began to pee in his pants, resulting in a dark stain on his light grey school trousers. When I asked him whether he didn't feel it coming, he said "No, Mum, it's sort of like an ambush:" He always had a facility with words and that one hit it on the head. Our bodies do ambush us from time to time.