The Things We Carry

The brief, blazing life of Michaela DePrince, war orphan turned ballerina, and the myth of overcoming

When The New York Times reported that Michaela DePrince had died at 29 after a boundary-breaking rise from war orphan to acclaimed ballerina, a shiver of grief ran through me. I’d remembered her story for a good dozen years. Of seven young dancers profiled in the documentary First Position—not one of them short on tenacity or talent—it was Black, bold Michaela, then 14, who leaped off the screen and into my imagination.

She could have died in her native Sierra Leone—killed like her father, starved to death like her mother, shamed and neglected at the orphanage where she was the lowest of the low. The staff called her “devil child” because of her spotted skin, the hallmark of vitiligo, a pigmentation disorder. No one would want her, they said. If Oliver Twist had been an African girl, different from the others and surrounded by war, he’d have been the child then known as Mabinty.

Dreams are supposed to make all things possible. Four-year-old Mabinty had a dream. The wind blew it to the orphanage gate—a dusty copy of Dance Magazine. She reached out and held in her hands the very essence of beauty and joy, the cover ballerina. Mabinty never imagined such creatures existed, creamy-skinned and bespangled and floating on pink satin toes. She just knew she had to be that girl. The magazine became her talisman.

Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Sea Maid, whose story was a mainstay of my childhood, set her heart on walking the land so she could win the heart of a handsome prince. A sea witch promised to replace her fish’s tail with legs, but at a terrible cost: “No dancer will be able to move as lightly as you; but every step you take will be as if you trod upon sharp knives, and as if your blood must flow. If you will bear all this, I can help you.”

To pursue a career in ballet is to tread on sharp knives with bleeding feet.

Mabinty didn’t have to bargain with a sea witch. A great-hearted American woman adopted her and swept her away to the land of plenty, along with her only friend from the orphanage. Elaine DePrince embraced her new daughter’s dream. She and her husband Charles, both white, had the means for tutus, pointe shoes and top-flight ballet training. When Michaela fretted over the spots on her skin, Elaine called them “fairy dust.”

To pursue a career in ballet is to tread on sharp knives with bleeding feet. A student who happens to be Black will face an even greater obstacle: entrenched racism. She’ll have a big butt, teachers say. She’ll be too muscular. And who ever heard of a Black Clara starring in The Nutcracker? Michaela had no sooner won the part than she lost it because of her skin color. She might have had it easier as an athlete, a singer or a writer, to mention a few careers less infused with the tropes of whiteness. But Michaela was not about to quit on her passion.

“Follow your passion,” kids are told, meaning “Follow your burning desire.” Yet “passion” descends from the Latin “passio,” to suffer or endure, as in the passion of Christ: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

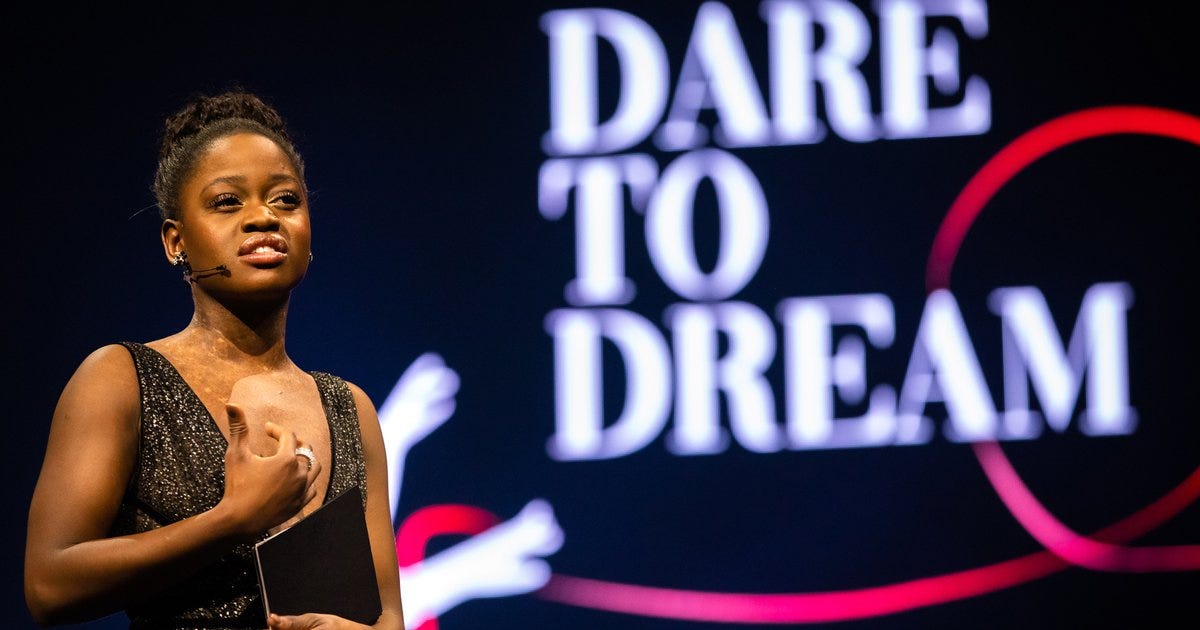

Michaela’s family has not disclosed the cause of her death on September 10. As I write this, the news does not appear on her website. She blazes in a red tutu, laughing as she leaps, all ten fingers extended as if she’s just thrown handfuls of delight upon a cheering crowd. Online, her story is nothing short of triumphal. Soloist with the Dutch National Ballet, model for Jockey and Nike, featured performer in a Beyoncé video album, author of the widely praised memoir Taking Flight. She met Angelina Jolie, spoke with Barack Obama. An ambassador for War Child, she advocated for kids in the world’s most dangerous places. I could go on, but you get the point. She seemed to be living her mantra: “Never be afraid to be a poppy in a field of daffodils.”

I comb Google for interviews and videos. Michaela pirouettes, she sparkles. She weeps for the kindly teacher in Sierra Leone who told her what a ballerina was and sealed her ambition to be one. This teacher was pregnant when men set upon her with machetes and hacked the fetus from her womb. When Mabinty tried to protect the only adult she could trust, the men slashed her stomach. In some of her interviews, she speaks glancingly of nightmares and mental health concerns. Young black dancers looked to her as a role model, as the press well knew. Who doesn’t love a story of obstacles overcome? “If she did it, I can do it do,” the story says. Yet every time Michaela recounted her past, she was compelled to relive it.

I have given keynote speeches about “overcoming” depression. The wording changed when it dawned on me that no one “overcomes” anything. Like you, like us all, I carry my whole life, both the wonder and the weight. The contents of my bundle shift with circumstance, and over time I’ve become more adept at balancing my load. There’s a reverence to it, and something akin to muscle memory. Jack Gilbert describes the process in his poem “Michiko Dead,” about the loss of his wife:

He manages like somebody carrying a box

that is too heavy, first with his arms

underneath. When their strength gives out,

he moves the hands forward, hooking them

on the corners, pulling the weight against

his chest. He moves his thumbs slightly

when the fingers begin to tire, and it makes

different muscles take over. Afterward,

he carries it on his shoulder, until the blood

drains out of the arm that is stretched up

to steady the box and the arm goes numb. But now

the man can hold underneath again, so that

he can go on without ever putting the box down.

We all carry the losses of an ordinary life. Some must also carry trauma unimaginable to anyone who was not there. Tim O’Brien, a Vietnam veteran and winner of the National Book Award, wrote a breathtaking short story, “The Things They Carried,” in which a platoon of grunts try to stay alive one more day after witnessing the death of a fellow soldier. “Humping,” as marching was known, might seem a far cry from dancing Swan Lake. Yet the soldiers, like Michaela, carry talismans: a girlfriend’s pantyhose, a grandfather’s hunting hatchet, letters signed “love” from a pretty young woman who felt nothing of the kind.

By turns bored and terrified, the grunts carry many pounds of weaponry through “the humidity, the monsoons, the stink of fungus and decay.” They carry their weary selves “with a sort of wistful resignation, …with pride or stiff soldierly discipline or good humor or macho zeal. They were afraid of dying but they were even more afraid to show it.”

A good soldier is a stoic. So is a ballerina.

Michaela’s Instagram feed is now a river of dismay. A multitude of fans thought they knew her. I did too. Some children have a spark that endears them to adults, and she was that kind of child. Looking up at the screen all those years ago, I saw the bruised hope that shone from her, the preternatural gravitas in her smile. I saw the flaring poppy she would become, forgetting that the sylphs and swans of ballet wear white. The gifts she carried were every bit as powerful and real as whatever took her down. I’ve read that she was known for what dancers call “elevation,” the propulsive jump that defies gravity. Had the luck of a day been different, she might be flying still. She might be on course to grow old and carry—with her dancer’s grace, her strong yet supple core—the things that must be carried.

Your turn now, everyone. What helps you carry the things that must be carried? Is there such a thing as “overcoming?” Do role models bear an impossible burden? (Loaded question, I know.) Wherever you take this discussion, it’s going to be rewarding.

If you found this post meaningful, head over here to learn how a dog protects my mental health. And here’s my post on the teenage ballerina who modeled for Degas’ beloved “Little Dancer.” Poverty, not dreams, pushed her into ballet.

All my posts are free to read, yet some readers of heart and means are paying for subscriptions just because. If you are so moved, I’d be incredibly grateful. No pressure, though. I’m here to meet a community of readers, and you are all among the great joys of my life. Feel free to share—you’ll be spreading the word about Amazement Seeker.

A tragic story. There are so many tragic stories. I've got a box full. They're not all mine, but I carry them for myself and for the others whose lives I'm connected to. The stories of my ancestors, the people closest to me, my neighbors and acquaintances. I carry those stories within me, but none weigh as much as my own. I carry them as a way to pay honor to the people who've endured. Thank you for this essay, Rona. Beautiful and wise as always.

My, my, you are a quiet bunch today. Many are sharing this post, very few are chiming in. John Callahan, the quadriplegic/alcoholic cartoonist and author of the memoir DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET FAR ON FOOT, was bitterly funny on the subject of inspiration. He offended many but his work appealed to my black sense of humor. One of his most famous cartoons appears in this article. If you find it offensive, you have been warned. If it makes you laugh, don’t miss his book.https://ability360.org/livability/callahan-and-me/