The Sentence That Hooked Me on Words

Everything I know about language goes back to the first line in the first book I loved. One great sentence can launch a whole story.

I was no more than three when my mother cracked the golden spine of the book that would change my life. I leaned close, waiting for her voice to unlock the words like the most magical of keys. She always read in a confiding tone reserved for story time, the one oasis in the day when there was nothing to cook or plan or write for My Baby magazine; no misplaced doll to find, nothing but the world about to open for my personal delight. This book, The Sailor Dog, was not like the others. The first line called to me with a verbal trumpet blast: “Born at sea in the teeth of a gale, the sailor was a dog.”

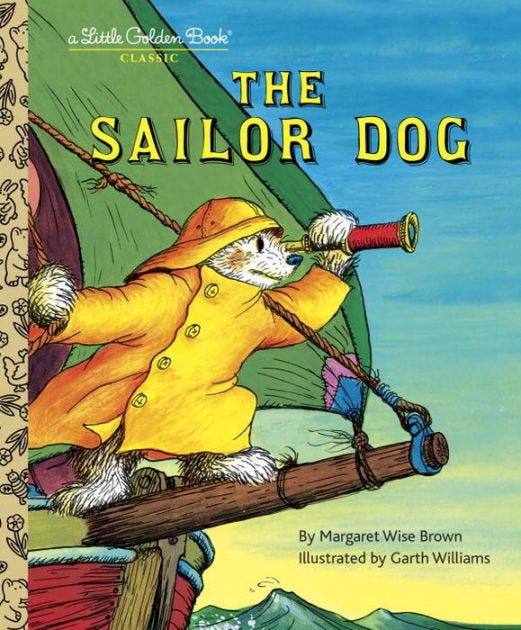

Margaret Wise Brown wrote more than 100 picture books before her death at 42. Her most famous, Goodnight Moon, became an icon of childhood, selling more than 40 million copies since it first enchanted kids in 1947. The Sailor Dog is a connoisseur’s pleasure, one of Brown’s more obscure collaborations with the peerless children’s illustrator Garth Williams (of Stuart Little, Charlotte’s Web and the Little House books). On Goodreads one Susie Lipton, a pediatrician in Freeland, Maryland, says it calms young patients during asthma attacks and chemotherapy. Susie, my soul mate, I could hug you. But our beloved book has vehement detractors. “One of the worst children’s books we’ve read,” says Carissa of Round Rock, Texas. “The prose is weird.”

The Sailor Dog is closer to poetry than prose. The first sentence works on the mind, young or old, the way poetry does, with the power of rhythm and association. Brown creates a verbal kaleidoscope, gives it a spirited shake and lets the everyday land beside the arcane in a design that sparkles with newness.

I time-travel back to the stout green sofa where I curled up beside my mother. What was a gale? How could teeth be anywhere but inside someone’s mouth? I didn’t need to ask. I cared only for button-eyed Scuppers at the helm of his ship, clutching the wheel as waves pummel the deck. Garth Williams made his plight as real as our living room, with its pine-paneled walls and stack of Life magazines. The dog was little, like me, testing himself against something bigger and wilder than I could begin to imagine. I held my breath for Scuppers.

Born at sea in the teeth of a gale, the sailor was a dog. You must read it aloud to hear the music soar.

Let’s slow the music down. Bear with me while I exaggerate the cadence. BORN at SEA in the TEETH of a GALE… The stressed syllables beat like a drum, hard and solemn. Then the sentence begins to lilt: the SAIlor WAS a DOG. Da DUM, da DUM, da DUM, three iambs, as they’re known to scholars of English. The Lego blocks of the canon (as in “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”) When Brown frees the lyrical iambs from the sharp teeth of that gale, suspense rises. The sentence gives its full narrative force to a statement of identity that feels both a tad off kilter and hauntingly right: “the sailor was a dog.”

An author’s best friend is an editor who gets her. Brown worked with the pace-setting Ursula Nordstrom, who also championed Maurice Sendak and Louise Fitzhugh. An old-school fuss-budget would have had conniptions. “Really, Margaret! You’re talking to nursery schoolers, not doctoral students in the poetry of Yeats. And why on earth do you back into the story with an adjectival clause? ‘Born at sea in the teeth of a gale…’ Oh dear. We need to simplify this flight of fancy: ‘A dog was born at sea in a storm. He knew that he would be a sailor.’ Isn’t that what you mean to say?”

No, no. At three I couldn’t have told you what Margaret Wise Brown meant to say. But I felt it in my deep heart’s core. The Sailor Dog is a story of identity forged in adventure—of following your north star wherever it leads. The world will deem Scuppers unfit to be a sailor; he knows he can’t be anything else. His dogginess and his vocation twine like the fibers of a rope. Brown could have written, “the dog was a sailor,” but the sentence would have ended with a whimper. So she gave it an emphatic bang: '“the sailor was a dog.”

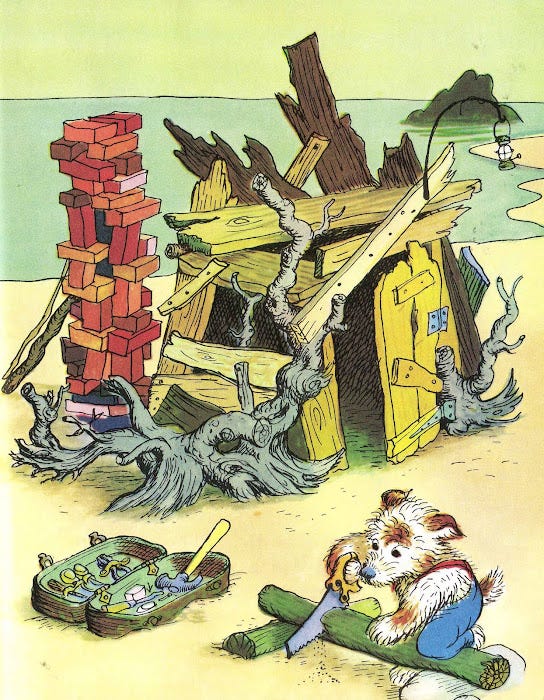

Still with me? Look at the first word, “born.” The first and last words command the power positions in a sentence. This particular sentence guides the ear and eye from “born” to “dog,” driving home the canine hero’s destiny. While pursuing his dream, Scuppers will be shipwrecked. But he’ll rebuild his boat—by himself, out of driftwood. Like writers who labor alone to put one line in front of the last, he doesn’t know any other way to be his essential self.

The sentence that hooked me on language contains 14 words—including, “a,” “in” and “the.” Explaining its power just took me five paragraphs. You could let it transport you on a wave of emotion, as I used to do on the story couch. But if you want to write sentences of beauty and heft, you’re wise to look closely at how the masters do it. In my personal museum of masterful sentences, “Born at sea…” is up there with the best.

Did Margaret Wise Brown meditate on stressed syllables and iambs? Did she analyze as she wrote? I doubt it to the bottom of the sea and back. She had a north star of her own, authorial instinct. She trusted that children want “a few big gorgeous grownup words to bite on,” according to an essay in The New Yorker. She jotted down first drafts on the fly, then refined them for as long as a couple of years, considering how one line danced with another. In psychoanalysis she mined her dreams for inspiration. “A child’s own story is a dream,” she once wrote, “but a good story is a dream that is true for more than one child.”

Scuppers used to live between the covers of my Little Golden Book. Now he sails my imagination as I write. Halfway through my seventh decade, a rescue dog bounded into my settled life and proceeded to expand it in a heart-swelling burst of discovery that set me to work on a memoir. My pointy-nosed hound looked nothing like Scuppers, but when the book ran aground I channeled my canine hero. I tinkered with verbal driftwood, hammering sentences into place only to rip out them out the next day. I listened, as Margaret Wise Brown surely did, for inner music telling me I was getting somewhere.

Last spring, after half a dozen fitful years of work, I finally launched Starter Dog: My Path to Joy, Belonging and Loving This World. I filled the hold with my inspirations, from bees and blackbirds seen on morning dog walks to the books on my shelves. This book of mine pays tribute to poets adults read—Elizabeth Bishop, Emily Dickinson, Mary Oliver—but also to Margaret Wise Brown. You are never too young for the rapture of language—or too old to let it take you somewhere entirely new.

And there you have it, friends—my first post on writing. In 70 years of stories—the living, the writing, the ardent contemplation of reading—I’ve gathered a hoard of things to share about the craft. They’ve been ripening while I found the way in. You don’t need any more writers’ prompts, and I don’t use them anyway. But I think there’s a place for stories about story, so that’s you’ll find here from time to time.

Over to you. Is there a book that made you a lover of words? Let the conversation begin.

How fortunate am I to work in a children’s library?! Thank you, Rona, for reminding me what a treasure I have in my latest, and most likely, last, occupational endeavor (of my otherwise previously lackluster jobs).

Almost each shift, I discover yet another gem from my childhood.

Isn’t it wonderful how a simple sentence can be a prelude to one of our best adventures in life?!

Loved this! I agree there are enough writing prompts in the world but not enough of this kind of close critical reading of what makes a story work. I look forward to reading more of your musings on the craft of writing!