The Green, Green Grass of Gettysburg

I thought I heard a promise in Lincoln's greatest speech. Then I stood where he gave it--and finally got the point.

One golden afternoon in the mid-aughts, on our way to visit friends in Philadelphia, we pulled off the highway for a look-see at the Civil War’s bloodiest battlefield. We could spare at most two hours for Gettysburg. Just long enough to inhale some valor and stand on the spot where Lincoln gave the Gettysburg Address. His cadences had rung in my head since high school. They guided me as a writer, each word resonant and severe, like organ notes that summon the choir to stand. They rooted me in the story of my native land—the soaring aspirations, the near-fatal rupture.

Gettysburg is not a look-see kind of place. History buffs allow three days, the length of the battle that left some 50,000 casualties and 7,000 dead. The visitors’ center proposed a drive with 16 stops. Limited to one, we chose stop 15, site of the legendary rout known as Pickett’s Charge. The rebels had planned to invade the North and batter Union morale. On July 3, 1863, the high tide of the Confederacy, they met their match at Cemetery Ridge.

Under the bluest sky, on the greenest grass, we looked down on the last view that many ever saw. Across a picture-book valley rose the line of trees where 12,000 Confederates gathered before surging toward the ridge, easy targets for the Union troops on high. I was imagining the wave of death as a passel of teens broke loose from a yellow school bus. It was prime field trip season, late May or early June, the season of wandering minds and hormonal explosions. When teachers can’t get any teaching done, they might as well delegate a lesson to the grass at Cemetery Ridge.

High-school reenactors tore across the ridge, leaping and rebel-yelling. They rolled on the ground in their loudest imitation of death throes, heedless of the boys who died where they frolicked. No one makes more noise, or consumes more space while careening about, than a teenager itching to jump into summer. Once upon a time, our house shook with the thump of teenage feet on our stairs. Our son and his friends couldn’t just descend those stairs; they had to lay claim to every one.

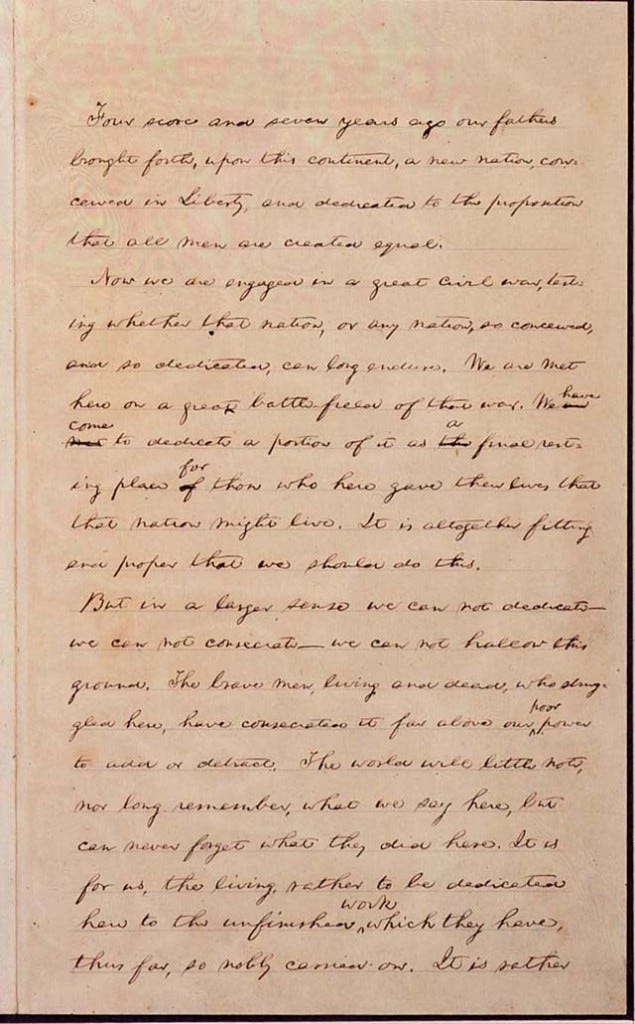

We checked our watches: time to commune with Lincoln at the National Cemetery, where he pulled from his pocket the dedication speech, written on a single sheet of paper and delivered in all of two minutes. The other speaker went on for two hours.

I never loved a human at first sight, but I was smitten in a flash with the Gettysburg Address. I must have been 16—same age as those kids pouring out of the school bus, give or take a year. Dylan lyrics on the cover of my American history notebook.

Language had enchanted me since toddlerhood, and Lincoln’s carried me away. His music tolls and swells. Seven repetitions of “dedicate” or “dedicated,” each one gathering power from the last. The Biblical archaism of the opening flourish, “Four score and seven years ago.…” In the last lines, I thrilled to what seemed the American promise: “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

The Gettysburg Address is a challenge, not a promise. At 16 I slipped into the trap of wishful reading.

Reading those words where Lincoln spoke them, within strolling distance of some 3,500 Union graves, unleashed a primal grief. I’m not one to cry in public, but the Gettysburg Address undid me.

That mild afternoon, I had no fear for the republic. I couldn’t imagine an America in which election denialists would storm the Capitol—wielding baseball bats, assaulting police, threatening to hang the Vice President—or that, four years later, a duly elected President would pardon the rioters en masse for their crimes.

If Lincoln could witness the torrential abuses of the new regime, they would chisel deep new grooves in that most melancholy Presidential face. Yet I doubt he’d be entirely surprised. The Gettysburg Address is a challenge, not a promise. At 16 I slipped into the trap of wishful reading.

In 1863 the young republic was fighting for its life. The Civil War would grind on for another 17 months, putting the American ideal to the test. Lincoln centered his speech on dedication: the founders’ to the bold “proposition” of equality (by no means a truth universally acknowledged), the Union soldiers’ for the republic, every citizen’s to the “unfinished work that they so nobly advanced.” The republic, Lincoln told us, is at once magnificent and fragile. Without protection it will die—and the world will lose a beacon.

The Gettysburg Address has the precision of a well-made poem, ringing in at 272 words. I would need at least twice that many to enumerate words and at least one comma of particular beauty. On each rereading I make a new discovery. Yesterday it was a sentence of startling plainness, a Shaker chair in words. At 16 I’d have skimmed right past this sentence, in which Lincoln spoke to the ceremony of dedication: “It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.” The voice I hear in this line is not the great orator’s but the mourner’s. This is how wives and mothers must have spoken, eyes glistening, as they laid out their dead. The sentence is Lincoln’s hand on the shoulders of the bereaved.

I often told myself, back in Trump’s first term, “We’ll survive this. We survived the Civil War.” A reasonable enough proposition, it seemed. The Civil War killed 620,000 soldiers on both sides, leaving an entire generation of widows and fatherless children. Identifying the dead, recording last words and transporting bodies home became fixations for the public and the press. To survive such a conflict was a formative passage for the nation. Yet here we are as a President assumes the powers of a king.

Lincoln called Americans to action. He could have challenged us to resolve “that these dead shall not have died in vain.” He went a step further, pulling all Americans into the moment at hand: “We here highly resolve…” (my italics). These words do not trip off the tongue. They march with gravitas from Gettysburg to the present day. Saving a republic takes the highest resolution. It demands everything we’ve got and then some.

And now for the highlight of my week: your comments (you surprise and delight me every time). Have you ever stood where something momentous happened? Ellis Island, maybe? Stonehenge? If you are American and haven’t been to Gettysburg, you’re missing out on a memory to treasure.

My thanks to , community builder extraordinaire, for inspiring today’s essay with her call to contributions to “a virtual library of hope.” I hadn’t meant to write about this American moment on the heels of last week’s post, “A Tale of Two Countries,” but I couldn’t resist this project. To join in, head over to “The Hallelujah Book & Hope Letter.”

See you next week with a completely different amazement—whatever calls “Write me” most ardently. I have to care about the piece at hand; if I don’t, why should you? While all my posts are free to read and will remain so, paid subscriptions have a special power to cheer me on. Honestly, though, I’m not in this for money. I’m in this to connect with you, and there are lots of free ways to help me grow this community. Share a post, leave a comment, recommend my stack on your yours, or simply click the heart. That’s what writing comes down to: the heart. First, last and always.

P.S. for American history buffs: Drew Gilpin Faust, a historian who made history as Harvard’s first woman president, has written a poignant and approachable book about the Civil War’s impact on American life, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil. Highly recommended.

This is one of the most stunning essays I've read from you, Rona. Gorgeous, necessary. Reminding us of the proposition, of what's possible, and no, it's not a promise. But it could be if enough of us remember and re-up. I'm so grateful to you for this work today. I find it centering and bracing. May it spark new commitment in the hearts of so many of us who feel disillusioned, displaced, and scared. Thank you, Rona.

In the autumn of 2013 I lived in Fredericksburg, VA - about a half mile from the Rappahannock River, near Telegraph Hill and the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. The 150th anniversary of the Battle of Fredericksburg was coming up in December and there were events and demonstrations going on all over.

One morning I woke to a thick fog slowly giving way to the early sunshine, the scent of damp leaves and a hint of frost in the air. I'd fallen asleep with my windows open - and I'd been awakened by the sound of cannon fire, musket fire, and the vibrations felt all the way to my third floor apartment.

For a moment, in that not-fully-awake stage, I felt a surge of panic and fear - and when I sat up and realized what was going on, I thought about what it must have been like to have lived through it back then.

Those times when we're given a sense of the enormity of a slice of time are precious gifts and a charge to do better.