Testaments of Friendship

When a teen was murdered, her letters went missing. Sixty years on, could her friends get them back?

A similar version of this essay appeared in Dorothy Parker’s Ashes, another in an early post here. Some stories never let the writer go. This is one.

Snow was falling thick and fast on Manchester, N.H., when 14-year-old Pamela Mason made dinner for herself and her younger brother, then left for a babysitting job. The man waiting in his car had answered her notice in a laundromat. It was January 13, 1964.

Pamela never came home. When news broke of her disappearance, a collective shiver went through my high school in Durham, thirty-four miles away. She was Pam to us—a classmate of mine until her family's recent move to Manchester. All of us girls had been warned not to get into cars with strange men. We'd heard the stories of abductions and grisly discoveries, been chilled by the occasional headline about a girl who met a bad end.

When Pam appeared above the fold, I recognized her lustrous hair. I wanted to feel only sympathy and fear for her, but guilt knotted itself around my heart and squeezed. Hair, to a girl of 14, is the emblem of all things that matter. I didn't like my own flyway curls ("frizzies," we said then). And I had never liked Pam, who made no secret of her disdain for me.

In my only memory of her, we’re reluctant cooking partners in Mrs. Boynton’s eighth-grade home ec class. Pam and her girlfriend get busy with the wooden spoons while I stare out the window and wait for the bell to ring. The girlfriend mutters, in a tone calculated to get my attention, “All Rona knows is Shakespeare!”

I want to know who Pam was before her photo made the front page of every newspaper in the state.

Pam chuckles while stirring the muffin batter. She has the take-charge bearing of a girl older than her years, an ace with blown fuses, colicky babies and other predictable annoyances of adult life. With her amusement, she puts me in my place, which I have earned with my willful disregard for muffin tins. I’m so famously inept at home ec that I failed Mrs. Boynton’s test on white sauce by proposing this recipe: Dump everything white into a pot (sugar, flour, milk, marshmallows) and bring to a rolling boil. Nobody wanted to be my cooking partner, but Pam and her friend are stuck with me. I take a wild stab at winning their respect: “Shakespeare? I hate that wherefore-art-thou stuff!” While I rant about Shakespeare, Pam gets on with the task at hand.

I’ve forgotten the scorn of countless other classmates who were not swept away in the night. Yet I’ve replayed the muffin-making scene countless times. Pam’s image never quite comes into focus. I think I see a pencil skirt and cardigan buttoned to the neck. I’m pretty sure about the hair—a shining beehive, like a Seventeen model’s—because I’d tried to copy that style, but bobby pins couldn't hold my wayward hair. I want to get the details straight, to know who Pam was before her photo made the front page of every newspaper in the state. Before her prettiness and poise were exposed as no stronger than a moth’s wing.

I thought she had earned a small comeuppance. Not this. I burned with self-disgust.

Pam’s mother pleaded from the headlines for her daughter’s life. My own mother showed no sympathy: “Where was she when her daughter took that call? What kind of mother lets her daughter go off in a snowstorm with a strange man?” A single mother, working nights at the Holiday Inn to support her children. What was she to do? And why blame her for the guile of a man with evil on his mind? I felt ashamed of my mother, and of myself. I had always thought of women as the sympathetic sex. Yet here we were, passing judgment and competing for illusory rewards. Most vigilant mom, most desirable wife-in-training. I didn’t miss Pam, yet I missed the world her disappearance had erased. That place where I could trust that my mother knew the score. Where mean thoughts occurred only to popular girls, not to hapless outsiders like me.

Eight days after Pam went missing, a trucker noticed a purse and schoolbooks in a snowbank by the side of a highway. (Of course, she’d brought her books; she was an honor student.) Her body lay nearby. This much I had more or less expected; even kids know what becomes of Headline Girl. What I didn’t expect was the brutality Pam had endured—raped, beaten, stabbed and shot.

I thought she had earned a small comeuppance. Not this. I burned with self-disgust.

Where was the wise grownup to help me find the words for my feelings? I looked for a large-hearted listener, an unflinching witness to pain and bewilderment. My mother, it was clear, would not be that person. And while I had several teachers with a rare understanding of the adolescent heart, I don’t recall them speaking of Pam. Only two months had passed, almost to the day, since the assassination of our President, the boyish and buoyant John Fitzgerald Kennedy. The whole country was still in mourning—still stricken by Jackie's blood-stained suit, the three-year-old saluting his father's coffin, and the riderless horse—when Pam’s body was found.

I thought I’d let Pam’s memory go but the killer’s triumph made me ache for her.

Grownups had always seemed so sure of themselves. Now they looked blank and uncertain, as if shaken out of a dream. They still kept us in line, enforcing curfews and marking exams. But their secret was out: They couldn’t keep us from harm. As it turned out, they couldn’t even get justice for Pam. Overwhelming evidence supported the conviction of her killer, Edward Coolidge. But when it came to how the evidence was gathered, Coolidge found a loophole. He appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, which determined that the search and seizure of his car were unconstitutional. After twenty-five years in prison, he walked out a free man.

I thought I’d let Pam’s memory go, but his triumph made me ache for her. I blogged about her, and people from Manchester found my post. They’d been searching online for traces of the girl whose life touched theirs, if only in passing. I shuttered the blog long ago but saved the comments for the pent-up eloquence of people giving voice to their anguish.

Said Lynne, the sister of Pam’s best friend in Manchester, “My sister never really recovered from the incident, as she was called to testify at the trial…. She was called first to babysit for the monster.” Martha’s father prosecuted the case against Coolidge and carried a lasting sense of defeat; she told me her family still thinks of Pam. Susan lived up the street from Pam and was shoveling snow with her sister the night Pam was taken. “It gives me chills as I realize that the car she was in drove past… as we continued to shovel, totally unaware of the horror that was taking place. We had heard screams, but we always did since kids used to yell as they drove on that hill…. Since that time, every snowstorm brings me back to that night.”

If Pam were alive today, she’d be around 75. I’d be meeting her on Facebook with other former classmates I never really knew in school and have come to consider my tribe. We admire new grandchildren, mark the passing of spouses and siblings with condolences rooted in our own losses. Pam, the first one of us to be mourned, would be a mourner herself by now, finding comfort in her garden or her quilting group. Virtual smiles and waves would flow between us, and flashes of childhood memories that affirm the importance of those days. I might correspond with Pam as I do with her close friend Marie, whom I ignored at school because it seemed we had nothing in common.

I know what letters meant to girls in the days before texting—what old letters still mean, tucked in boxes.

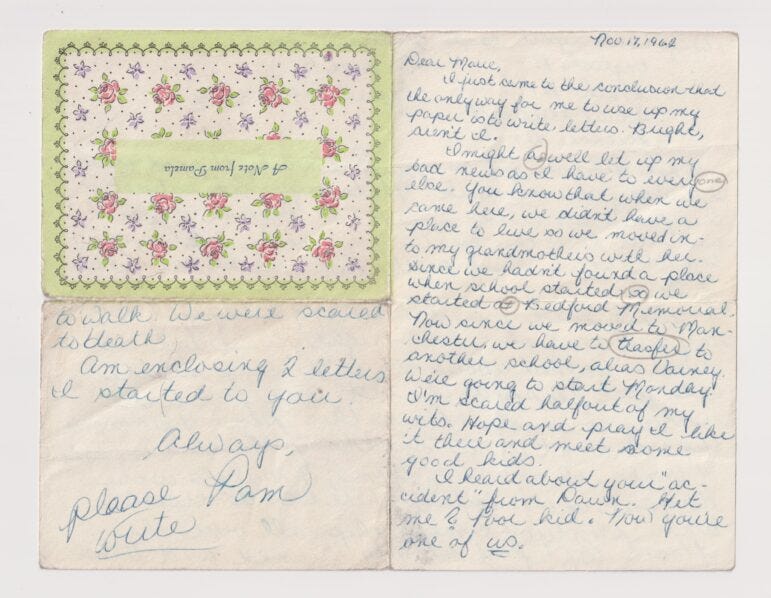

Every exchange with Marie returns to Pam sooner or later. When she disappeared, two detectives interviewed Marie. They paid scant attention to her answers; in their eyes Pam had run off with some boy. Then they took all the letters Pam had sent to the friend she missed with all her heart. I know what letters meant to girls in the days before texting—what old letters still mean, tucked in boxes. While my best friend was on vacation with her family, I waited ardently for envelopes addressed to me in penmanship that darted and swirled, like our conversation. Long after she died, I open her letters and hold our young selves in my hand.

Among the Facebook friends who read an early version of this essay was Rosemarie Rung, a state legislator in New Hampshire. When she offered to track down the letters, Marie and I dared hope they still existed in the dustiest corner of a basement. As months went by without a word, I concluded that heedless grownups lost them, along with the chance to lock her killer up for life. I hadn’t bargained on Rosemarie’s persistence.

When a clutch of letters came back to Marie, it seemed Pam and I were finally done. I could write a tidy conclusion to a story close to 20 years in the telling. But from the start, the story has transcended my words. It has been a call and response, ever since Lynne, Martha and Susan found my vanished blog post. As Marie held the stolen friendship in her hand, I shared the updated story on Facebook—and heard from another friend of Pam’s. She too had letters carried off long ago by detectives. Now she’s got them back.

There’s a reason I haven’t shared her name. She was the girl who made the Shakespeare quip. Bullying, she called it in her apology. I’d call it just one of those offhand cruelties that slip from every kid now and then. But this observation of hers made me smile: “I owe you about 60 years of gratitude. You did it, girl!”

When Pam’s letters came home to her friends, a little of me came home too.

Has an old letter ever brought you comfort or expanded your life? Tell me about it—or any other thought this essay sparked in you. I promise to answer, and my joy in writing has much to do with call and response.

Speaking of joy, the best part of old age is being, at heart, every age I’ve ever been—a trove of material for a writer. If you enjoyed this piece, check out “What I Wish I Could Tell My Gay Boyfriend.”

Share away—I’d be delighted. No paywalls here, and everyone gets to comment—paying, free or just passing through. It’s not that I don’t value the best writing of my life, rather that what I value most is my bond with readers like you. If you choose to pay, it’s because you have the means to send a little unexpected happiness my way. Lucky you. And me.

Do we all have stories like this one from our past? The story of Pam immediately triggered a memory of a girl I knew in high school, Linda Velzy who was picked up when she was hitchhiking in downtown Oneonta. She was 18, and he was a released repeat offender who ended up dying in prison. Her story haunted me for years, and though I never had a thought about hitchhiking myself, this sealed my commitment to never, ever taking that risk. Linda was kind, super smart and headed for a life filled with possibilities that was snatched away by a sick, evil man. As far as reclaimed letters are concerned, when my dad died, and I was going through his possessions as I packed up the things I'd keep and threw away the things we didn't deem necessary, I discovered a box filled with every letter and card I'd written to him over the course of our lives. They were eye-opening and for the most part, rather disturbing as I got to see how attached I was to him, how devoted, how codependent. I'm grateful to have them as I write our story. I'm glad you posted this story today. Our lives get upended in so many ways. It's good to be able to look at these things more than once. As I've aged, some of my perceptions have shifted. I'm lucky to have some documentation of the past to refer to as I write the stories of my life. xo

I found myself engrossed in this story and also have boxes of old letters. As you know, the old correspondence between my mother and myself provided much of the evidence and interest for my memoir. So I really resonated with the idea of old packets of letters.

This too, really spoke to me: “I didn’t miss Pam, yet I missed the world her disappearance had erased.”

it speaks to that litany of moments when our world changes, and we suddenly realize that things are possible that we never thought possible. In terms of human cruelty, human kindness, and people‘s true nature.