Tell Me Your Hopes and Dreams

I'll always miss the mentor who gave me to myself. Now it's my turn to light the spark in others.

In my first one-on-one with Keitha McLean, she rocked back in her chair, put her feet up on her shiny white desk and said, “Okay, Rona. Tell me your hopes and dreams.”

My new boss was clearly not the white-desk type. Her Western boots had tramped far and wide. Sweat bloomed in the armpits of her purple silk shirt. A storm of contact sheets and perfume bottles engulfed the command post where Miss Chatelaine’s former editor had kept her designer pumps firmly rooted to the floor.

I’d been hired to copy-edit a teen magazine. My pencil slashed at errant modifiers in “Your First Visit to a Gynecologist.” Keitha was dumping girlish fare. Canada’s young working women deserved a fashion magazine with straight talk about the issues on their minds. That morning in the lobby, she’d announced her vision: “We’re going to capture the spirit of the people who are making fashion happen. We’ll talk about fashion the way nobody has before, as new ways of living, not just new looks. The biggest talent in the country will be fighting to get into the pages.”

I couldn’t wait to be part of Keitha’s dream. But why did she care about mine? No one ever had before. I told her I’d like to find new writing talent.

“New talent? Why don’t you start with yourself? I’ve been reading your file. You’ve published fiction, won writing awards. I don’t know why you’re checking commas when you’ve got the chops for the fun stuff.” The best editors could write, she said. They didn’t get their jollies knocking other people’s prose around. She would know. A writer herself, she had published all over the English-speaking world.

She threw her arms wide, embracing everything she saw in me. Her red hair swung and gleamed. I never fell for any man as I did for her that day. Shape me, I thought. Show me the way. I’ll do whatever it takes to make you proud.

In my publishing career of close to three decades, I learned from a seasoned multitude. Mavens taught me the tricks of our trade, thinkers passed along mantras I still ponder today, miscast leaders showed, with their unwitting example, how to sap the motivation of a team. Keitha was my one true mentor. She saw in me what I had not yet seen in myself—the ambition I didn’t dare express, the yearning to speak in my own voice. As her columnist on topics from books to careers, her keeper of the freelance writers and her stylistic authority on every word we published, I had her permission to strive and to fail. She would say, “It’s a magazine, not the Sistine Chapel. You make it as good as you possibly can and then you let it go. Because next month, there’s going to be another one.”

Love kept me in that job long past the point of mastery. And what I loved was the person I became at Keitha’s side. Would that person still exist without her trill of appreciative laughter at my latest column? She underpaid me, knowing she could. Exploitation, my husband called it.

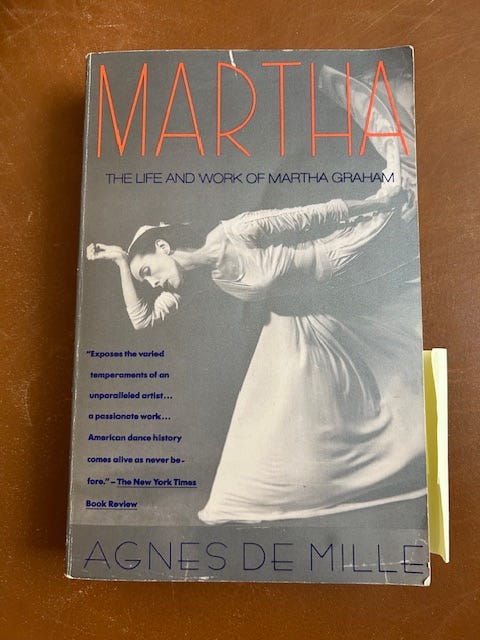

When Agnes De Mille was a young choreographer and dancer, she lucked out with Martha Graham as her mentor. Only De Mille could have written the biography Martha, which is partly the story of her own creative flowering while nourished, inspired and bedeviled by the Picasso of dance. Graham singed everyone in her orbit with tantrums, demands and flashes of cruelty. Mentorship awakened her tender side. “She came to all my shows and held my hand through the openings; she talked to me about the work afterward with perceiving grace.”

More than the art itself, Graham championed the spirit of the artist. She told De Mille, “There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it.”

Graham gave De Mille to herself. Precisely what Keitha did for me.

The fashion magazine known as Flare was not art, but Keitha gave it a sense of purpose that transcended the cut of a jacket. She had limped home to Canada in disgrace after an alcoholic flame-out at a big magazine in New York. Our little, low-budget magazine was the haven where she started over, guided by the 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous. In an Editor’s column, she spoke to readers about “those backsliding times, the days, weeks or months even, when what seems sensible is to pull the covers over your head and order in pizza all weekend, or drink too much or pop pills.” She championed “living like a grownup,” one mindful choice at a time.

At last I made the choice to leave her. I took a job at the newsmagazine upstairs. My salary doubled overnight.

Thirty years ago this month, as cancer burned through Keitha, I sat down to write her a letter. I pulled it up from a deep well of feeling, word by word.

Dear Keitha,

These days my mental pathways keep winding back to you, whether I’m shoveling out my in tray or walking in the park….

I used to dread writing because I knew the shame of a red pen slashing my work. I’d get so anxious about the details that I didn’t dare trust my own instincts. From you, I learned that God is not in the details. What counts is saying what you mean without apology or artifice.

There’s a wonderful poem by Emily Dickinson in which she contrasts two courses through life: doing menial work for small-minded taskmasters, and chucking it all to build a temple. I’ve always thought of you as one of those building the temple. You have been my inspiration.

Much love,

Rona

I sent the letter while finding my feet at the helm of Chatelaine, Canada’s leading magazine for women. Keitha had aspired to that job ever since we first met, but she was gracious when it became mine. I somehow lost her note about my first issue, but two lines ring in my memory: “I see the spunk emerging” and “Covers are always a long journey, no?”

That cover was far from my worst mistake, just the most conspicuous. Without the steadying guidance of a mentor, I had never felt so alone. I learned the art of leadership by trial and error. When I missed Keitha, I channeled her by mentoring others. I never asked anyone about her hopes and dreams. Instead I asked the clarifying questions that would bring hopes and dreams into focus.

One particularly gifted protégée, after mastering every challenge I could offer, landed the top job at Flare, the fashion magazine Keitha had launched back in 1979. My initial reaction was dismay. I counted on Lisa, as Keitha had counted on me. To my shame, I tried to delay the parting. Then it struck me that if Keitha could send me off to test my skills on a bigger playing field, I could find it in myself to rejoice for Lisa. Keitha had died long ago at 53. And yet she was with me still, cheering me on as I gave Lisa to herself.

Flare vanished two years ago, one more magazine crushed in the digital age. Keitha crops up fleetingly online, in fractions of a sentence with her surname misspelled. I picture her on Substack at 84, still learning to live like a grownup in full view of thousands of loyal subscribers. She’d be mentoring via Zoom and live chat.

I’m beyond lucky that we met in an office where the team gathered daily to laugh, kibitz and ask on the fly, “Hey, what do you think of this headline?” The one thing I miss about running a magazine is the constant, hopeful presence of people I could give to themselves in spontaneous bursts of connection.

Recently a young writer engaged me to coach her with a milestone essay. It soon became clear that what this gifted woman sought was not so much editing as mentorship. After a rich and clarifying virtual conversation, I asked if she would like me to review another draft. No, she answered. She understood the task ahead and was keen to get started. When I read the finished piece on her stack, it was my pleasure to applaud from afar. She had said what she meant without apology or artifice.

Good for her and her grateful readers. Good for me.

And now let the conversation begin! How has mentorship expanded your life—on either side of the bond? I can’t wait to see what you have to say. You’ll hear back from me, I promise (and maybe also from members of this lively and generous community).

You may have heard of “momentary mentors” who change your perspective with a single act or remark. When I met the writer Tillie Olsen, she challenged me to “fight unnatural silences,” not least my own. Here’s the story.

It’s been just about exactly a year since I began accepting paid subscribers. Some of you put your hands up before I opened the till. Everyone who chipped in—for a second year, a month or somewhere in between—has sent virtual flowers to my door, and I could not be more grateful. There are lots of other ways to lighten a writer’s heart. Comments, shares, likes on the fly… they all show me that you’re finding amazement here, just as I hoped when I welcomed my first readers 19 months ago. What a joy it is to have you with me.

This is lovely, Rona. I've had so many mentors in my life, and I find them in the most and least likely of places. Of course, my first mentors were the most wonderful teachers I had throughout my formal education, all the way back to first grade. My first grade teacher and I are still in touch, and she's in her 90s now and reads my essays on Substack every time I publish. But I've also had momentary mentors, they could be people, or 4-legged friends. I'm a sponge for learning, and am open to what others can contribute to me. It could be one instance that influences me so profoundly that it changes me forever. Now, I have writers like you (although none are really "like" you) who teach through example and are available for questions about growing as a writer. I'm so grateful for this arena. I wrote an essay just this week about someone I barely know who became a momentary mentor, I've known her for about 7 months, and she's near death now, but the connection happened. She's taught me a lot. Mentors abound! xo

I am a longtime fan of yours, Rona. My few writing mentors were far outnumbered by squashers. Probably the reason I worked primarily as an editor. At seventy, I’m starting over as a writer. Remembering that covers are a long journey.