Queen of a Very Small World

Her castle had 30 rooms. She lived it up in many bedrooms for lack of other places where a woman of her day could shine. I admired her and ached for her too.

My oldest friend was nobody’s crone. She died at 101 after holding court for decades in a house with 30 rooms, every one of them dense with treasures. There was a bust of Virginia Woolf, a carved blue heron that bobbled when you give its head a push, a light-up box that contained a brigade of painted Mounties, and a photo of the Queen of 30 Rooms with Eleanor Roosevelt.

“Your house is like a museum,” I once told her.

She glowed. “That’s right. A museum of me.”

We were sitting in her conservatory amid the remains of brunch: smoked salmon, bagels, croissants and imported preserves. She looked more glamorous in a terrycloth bathrobe and crimson nail polish than most of us could look after hours of expensive ministrations. She surveyed the orange tulips I’d brought and hastily arranged in a vase that wouldn’t do. “It looks like that junk they sell in hospital gift shops. You’d better find another.”

The Queen’s throne was a wheelchair by then, so my visits involved some fetching and carrying. Her husband had died long ago; a housekeeper stocked her fridge. Yet I hadn’t come to cheer up a lonely old soul. She was the one who did the cheering.

Her initiative put mine. When the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts unveiled a Saint Laurent retrospective, I lamented the inconvenience of catching a train to Montreal. I dithered so long, I never did get there. The Queen made the trip early on. Arriving at the museum, she asked in a ringing voice, “Who will push my wheelchair?” Several men vied for the honor, sensing a chance to be richly entertained.

I had been a faithful wife, which to her signified a lack of erotic imagination, a habitual derring-don’t that required correction.

I turned to her for solace after the death of my mother, who had been her friend and bequeathed their bond to me. At 40, I still yearned for a lodestar of maternal age and bearing. The Queen’s calling card said “Advice,” but I had to wait a good many years for the tip closest to her heart. I had been a faithful wife, which to her signified a lack of erotic imagination, a habitual derring-don’t that required correction.

“I love the word ‘affair,’” she said. “You should have an affair. What are you, 50, 60?”

The difference between 50 and 60, soul-churning to me, had become a trifle to the Queen. She was probably somewhere in her 80s then, not that she deigned to discuss her age. “You know, Rona, you’re still cute but you’re not getting any younger. You ought to curl your hair. Put on lipstick.” (The shade I had on was not the glossy, kiss-me red she’d have chosen.) She saved her most vigorous critique for my bra, “that soft little thing.”

In her youth the Queen fell consumingly in love with a musician who wouldn’t hear of fathering children (“He didn’t want to share me with anyone”). When she married it was not for love but for a shared vision of their future. Her husband enjoyed a distinguished career while she, as a woman of her time, presided over the House of 30 Rooms and the children who tore through it. She could have been a writer acclaimed for her sly wit (Fay Weldon with painted Mounties). As it was, she told subversive tales to her friends and carried picnic lunches to her lover of the moment, who waited at the Sutton Place Hotel. She had mastered the art of the discreet escapade: no room service (the waiter might have a loose tongue), no single men whose ardor might disrupt her kingdom.

In a burlap bag or a Dior gown, she’d have looked the same to her husband. Invisible.

Her bravado so amused me that many visits passed before I noticed the chink. She once told me of rushing home from a tryst in a dress she’d pulled on inside-out—her indiscretion on full display. There sat her husband in his favorite chair, paying her no mind. In a burlap bag or a Dior gown, she’d have looked the same to him. Invisible.

Sadness pierced me, but the Queen did not want my pity. She wanted none of the soothing words I’d have said to an invisible wife of my own generation, no “That must have hurt” or “Would you like to tell me more?” She and her husband had a deal. They kept it.

She managed her old age as she had her marriage, with no small measure of guile. If she hadn’t seen me in too long, she would call to announce, “I need attention!” Off I would go to the House of 30 Rooms via subway, bus and a not-inconsiderable trek on foot, wondering which slice of her past she was about to serve like a fruitcake in which every currant and fig has absorbed all the brandy it can hold. She always circled round sooner or later to her last encounter with the old flame of her youth.

They are two old folks meeting for a drink. Their faces sag, their bellies strain against their clothes. He looks into the eyes of the woman he refused to share with a soul, not even his own child, and declares, “You still have traces of your former beauty.” Her eyes sparkle, as she damn well knows. Her hair is a froth of curls. Old Flame has become a toad of a man. And yet he presumes to pass judgment on her beauty.

The nerve. I’d have torn a strip off that old coot. But the Queen chuckled at his foolishness. He did as men do and have always done. They can’t help themselves.

The first time I called on the Queen, she got around with a cane. The walker followed, then the wheelchair. Now that arthritis is having its way with me, I’m struck by how little she said about her pain, which must have been considerable, or the shrinking of her world as she lost mobility.

The last time I saw her, she lay in her bed, her voice a whisper. So it had been since her stroke. She missed nothing that I said. But I had always come for her stories, not the chance to tell my own. She couldn’t manage more than a sentence or so at a time. I bent my ear to her lips, her small pale hand in mine. The dynamic of our friendship had changed. Since she could no longer request my attention, I would have to give it of my own accord and expect nothing in return. I did not rise to the occasion. I let her go when she could no longer play the role I had assigned her.

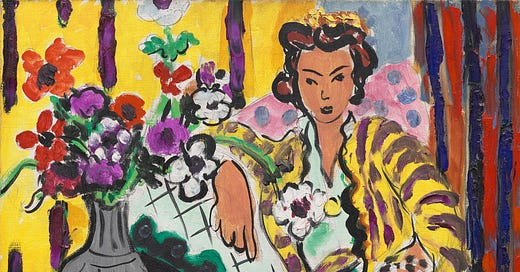

The House of 30 Rooms has been on the market for some time. I hate to think of anyone demolishing the Queen’s museum and erecting a monstrosity with a media room and a gym. Meanwhile a website takes me back to her domain. I ring the doorbell on the broad stone threshold. Pass the bouquet of dried roses, faded for so long that their color is anyone’s guess. The Queen’s paintings, bold and bright as her lipstick, hang on the walls. Sunlight streams through the conservatory windows. It’s time to set the table for our brunch. I won’t need long to find the good dishes. Although, to be honest, I’d welcome the delay. I’m past 70 now and still haven’t had an affair. I know what she’ll tell me: “You’re too late.”

The inside out dress, the invisibility, the agreement. How I adore outspoken older women. I sense your mother was robbed of becoming old and ever more outspoken. I had an aunt who was known in her town as the Gray Eminence. All the young women in the family aspired to be like her. Lillian Hellman and Beatrice Wood had a similar aura to your friend. I would like to wander her 30 rooms, or even three of them. You have brought her back to life.

I enjoyed this so much Rona. Beautiful portrait. Some lines were achingly sad.

"I did not rise to the occasion. I let her go when she could no longer play the role I had assigned her."

You inspire me to reach back in time and tell more of my own stories.