How to Keep a Friend

A tale of two artists--one famous, one a bitter unknown--and the bond jealousy couldn't kill

Father’s Day can sting for those of us disappointed by our fathers. I grew up wondering how mine could get away with his drunken tirades. Then I had a heart-to-heart with his oldest and most loyal friend. I first told the story back in 2024, thousands of readers and a few edits ago. It’s still among my favorite posts.

Forty-odd years ago, with a question on my mind and time to kill while passing through Vancouver, I went to see my father’s old friend Jack Shadbolt. His wife greeted me looking troubled and proceeded to explain herself. My father had repeatedly wounded her husband. To Doris Shadbolt, Max Maynard was poison.

Jack proposed to take me on a drive. For an artist of some renown, he drove a car of startling decrepitude, a station wagon that could still haul his paintings around but did not pass muster with his wife. She called from the doorway, “You know, Jack, you ought to get the brakes checked.”

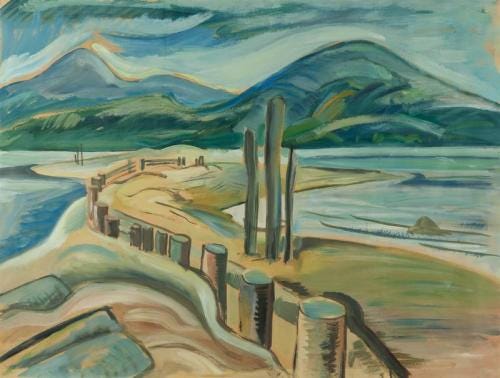

Jack was the friend of my father’s bohemian youth. He talked of that golden time the way Adam must have talked about Eden. With sketchbooks under their arms, he and Jack roamed forest and coast around Victoria, British Columbia, a stomping ground so beautiful it shamed every other place he’d known. Two modernist painters out to shake up their prim little city, they tagged along after the still-unknown Emily Carr until she tired of their attentions. Jack looked up to my father. Five years older, square-jawed and flashing-eyed, Max Maynard seemed the quintessential firebrand. He talked like one, too, in complete paragraphs that unfurled like an oration or a prayer. On their rambles he quoted Wordsworth. Splendor in the grass, glory in the flower. They would capture it and make their names.

Jack stayed true to his calling. He won awards and honorary degrees, represented Canada at the Venice Biennale. My father lost his focus. He ended up teaching English at the University of New Hampshire, where he spent his entire career as the lowest-paid man in the department (there were no women). With only a bachelor’s degree, he was lucky to have that job.

He often boasted of his friend the famous artist, but envy seeped from him. Jack lived the life that should have been his, painting in a mountainside studio in suburban Vancouver while Max Maynard painted after hours in the attic. Jack exhibited internationally; Max’s only gallery was our house. I’d never met Jack or seen any of his work except the modest water color he’d given his first mentor. “A poor thing,” scoffed my father, who hung it in a corner.

When my father made a sale, it was to a colleague, for a song. To them Max Maynard was a hobbyist, a maker of affordable décor to hang above the mantel. Some of them may have pitied him, shivering the winter nights away in that unheated attic. He would rage, “I could have been the most famous painter in Canada!” Unspoken words hung in the air: “if not for my wife and children.” Jack and Doris, a curator and art writer with a reputation of her own, had no children to put through college. They didn’t have to pay for ballet lessons, Christmas toys and Stride-Rites. They lived in a temple to Art.

According to my father’s moral code, Art with a capital A justified a certain recklessness with social norms.

I rejected my father’s take on his fortunes. If he didn’t want a family, why did he have one? Grownups lorded it over kids for their presumed equanimity and judgement, yet this grownup threw tantrums worthy of a two-year-old. He would berate Jack on the phone: “You’re a charlatan! A second-rater!” Long-distance calls were a luxury then, reserved for three situations: Grandma needed an audience in Winnipeg; one of us girls needed to check in from somewhere (we had five minutes); Jack Shadbolt needed to be put in his place.

I couldn’t replace Max Maynard with my notion of a good father (Ward Cleaver in a turtleneck instead of a tie). When it came to good friends, Jack surely had options. Yet he not only stayed on the line for my father, he came back for the next verbal beating. If any friend of mine called me names, I’d have cut that person dead.

According to my father’s moral code, Art with a capital A justified a certain recklessness with social norms. Other people might resent the final exams never marked, the fights picked at faculty cocktail parties, the scenes at the teak dinner table. But someone would always would cover for him (as my mother put it, “He’s a brilliant, original man”). No one mentioned the other A-word: alcoholic. Besides, who looks to Artists for propriety and selflessness? Gauguin left his family. Dickens too. Picasso, Hemingway, Kerouac, Dylan Thomas… world-class hellions all. Either Jack Shadbolt was a chump, or he followed a different code.

After I left home to find my own place in the world, I forgot about artists and their code. I worked in the magazine business, where you either pulled your weight or lost your job. I cut 100 lines on deadline, stood up to writers who accused me of destroying their voice. Jack Shadbolt fell out of my consciousness.

Meanwhile my father was returning to his creative roots. Retired from teaching and sent packing by my mother, he sought refuge in the one place he’d ever felt at home—Victoria. He rekindled ties with family and friends, not least Jack Shadbolt. He took up painting full-time and began to show his work. Arthritis forced him to substitute a palette knife for a brush, yet he flowered in old age. When the Burnaby Art Gallery mounted a one-man show, Jack wrote an appreciation for the program.

“His landscapes are all the same landscape,… a melancholic yet inwardly joyous cadence that never wavers.”

How Jack must have labored to express precisely what he meant, knowing his lifelong mentor and rival would scrutinize every word. He didn’t pander to my father’s vanity, even called Max Maynard “an unrealized artist” who “never produced the body of work his sketches hint at.” My father must have known this was the truth. But he’d have treasured Jack’s attention to his vision. “His landscapes are all the same landscape, …a melancholic yet inwardly joyous cadence that never wavers. They have a tidal rhythm….”

You think you’ll hold onto every detail of the conversations that change you, down to the angle of the light. But you don’t always know, in the moment, that you are being changed. The particulars fall through a hole in your pocket. Forty years later (or is it forty-two?), you try to piece the scene together from the one thing you know for sure—how you felt at the time.

The old station wagon lumbers up the mountain. Jack keeps his eyes on the twisting road. Somewhere around 70, he has color in his cheeks and fills his shirt. A slight paunch makes him look reassuringly substantial. My father has become a wraith—his throat a deep hollow, his nose a beak. He doesn’t eat much but still drinks, although he’s trying to work the Twelve Steps. His doctor tells me every system in his body is failing, but my father is a tough old coot.

I watch the city fall away and the sky open up. An unfamiliar lightness comes upon me, and a question floats from my lips. “Why is my father still your friend, after all the terrible things he’s said?”

Jack answers without hesitation. He was still in his teens when he met Max Maynard. A boy reaching for the purpose that took form on their adventures. They’ve had some 50 years together. You don’t throw that away because your friend is having a bad night. And while Max can be cruel, he has a keen eye for the gap between the painting on the canvas and the one in the mind of the painter. An artist needs a friend who understands the quest—the striving, the falling short, the starting over.

I thought friendship required an equal exchange of loyalty and devotion.

The road brings us to the foot of a chair lift, but rising higher isn’t part of Jack’s plan. I take in the peaks, the clouds, the great, undulating sweep of the landscape my father loves. He can’t speak of any place in coastal B.C. without exclaiming at its beauty. My mother used to roll her eyes: Here he goes again. What’s wrong with New Hampshire? But my father had a point. New Hampshire’s beauty is a string quartet, B.C.’s a symphony. Maybe that’s why Jack brought me here, to feel the vibrations.

We’re heading down the mountain when the car picks up speed. It flies around a curve as if making sport of the driver. Jack steers like mad. Doris was right, he tells me with a smile. The brakes just failed.

I have a primal fear of car accidents. It goes back to earliest childhood, when my father would grip the wheel to wrest control back from alcohol, that word never spoken in our house. At three or four, I dreamed he vanished from the driver’s seat, leaving only his fedora hanging in the air as our humpbacked sedan hurtled toward oblivion. Descending a mountain without brakes is my idea of horror. Yet Jack seems more amused than alarmed. His hands rest lightly on the wheel. Good God, is he chuckling?

When my father died, aged 78 years and 11 months, Jack gave a eulogy. I can still see him at the podium, miming his old friend’s exuberant freestyle. My father had been a fine swimmer; in his art Jack recognized the rhythm of his stroke. After the service, Jack followed as the minister led my sister and me into the little room where our father lay in his coffin, a husk inside a glen-check jacket with a red rose in the lapel. We bowed our heads as a door opened in the wall and the coffin slid into the crematorium.

I was coming down with the cold of my life, the swelling in my sinuses a wave of grief—not for my father but for the man he couldn’t be. A man with the steadiness of Jack Shadbolt. I let myself believe Jack was there to support Joyce and me. At 33, I hadn’t yet lost any friends. I couldn’t fathom why anyone mistreated by a friend would feel the need to witness that friend’s coffin given to the flames. I thought friendship required a fair exchange of loyalty and devotion. On the wildest drive of my life, I saw my father through Jack’s eyes.

Wonder of wonders, the station wagon came to a stop. The friend of a lifetime had gentled the beast. I would fly down that mountain again to sit next to Jack in his old beater, giddy with amazement at the ride.

Over to you, Amazement Seekers. How much grief would you take from a friend with one special gift? Where do you draw the line? Wherever you take this conversation, I love hearing from you. And I promise to respond.

All my essays are free to read. Paid subscriptions are rainbows.

This is a beautiful essay. Maybe Jack just loved Max. We forgive a lot of things for love. They seem to have filled a need one for the other. We don't always know why or need to.

As my father’s OTHR daughter, I’ll concur that Shadbolt’s generosity in the relationship must have been made possible by the security of his position as the far more acknowledged— and celebrated— artist. That, and Jack’s kind nature, surely explains much. But I have to disputes the assumption that Shadbolt was the superior artist. While I generally resist these kinds of measures where art is concerned, I’d argue that our father was every bit the artist his friend was and possibly more. This surely ate away at him.