How Do You Know You're in Love?

There are moments in the life of a couple when one determined soul must do the hoping and believing for two.

One weekday lunch hour in March, more than 54 years ago, I looked up from the shepherd’s pie on my tray to see a tousled young man approach my table with purpose in his eyes and a plastic shopping bag in one hand. He was no stranger, this fellow in the lumpy brown corduroy jacket. He’d come around my dorm before and left the jacket behind, his excuse to return and ask if I cared to join him at the diner up the street ( I ordered my usual, black coffee and half a grapefruit). He made me laugh; I’d give him that. Still, whatever possessed him to interrupt me and my pals as if he were my boyfriend, which he could never be in such a jacket?

I might have introduced him to my friends. “This is Paul. We’re acting together in The Seagull.” But manners were not my strong suit. From the bag he pulled a cardboard cylinder that he placed in my hands as if it were a bouquet of tulips. “It’s an eclipse watcher. I made it myself, to protect your eyes while you watch the eclipse of the sun.”

In full view of the group, I shoved his offering back. “I don’t plan to watch the eclipse, so you might as well use it yourself.”

So much for that, I thought. My friends must have thought so too. What’s got into Rona? Better watch out for her mean side.

There are moments in the life of a couple when the whole enterprise falls apart if not for one partner’s refusal to give up. Before we called ourselves a couple, we’d already arrived at the first. Eleven homes, one child, two grandkids, four cats and one rescue mutt after the debacle of the eclipse watcher, I asked Paul why he didn’t write me off then and there. He said, “I thought you had possibilities.”

At 20 I’d been waiting for love to come my way. It would arrive in a black leather jacket, not brown corduroy. In the pocket, e.e. cummings, not P.G. Wodehouse. My first gift would be earrings from someplace exotic, or a rare recording by an octogenarian bluesman known to Bob Dylan and precious few others. When no one appeared to match the image in my mind, I blamed either rotten luck or the willful blindness of young men. A sister student down the hall used to say of all disappointments, “The shit you shovel may be your own,” and it sometimes crossed my mind that she had the goods on me. If I deserved to be loved, wouldn’t someone love me by now?

My first line in Chekhov’s The Seagull, where I played black-clad, vodka-swigging Masha, expressed my entire world view: “I am in mourning for my life. I am unhappy.” Paul played my father, the comic relief. I wasn’t looking for anything so trivial as a good laugh. I had in mind the baring of souls by candlelight. But after nearly 55 years with my husband, I’ve crossed over to the laughter camp.

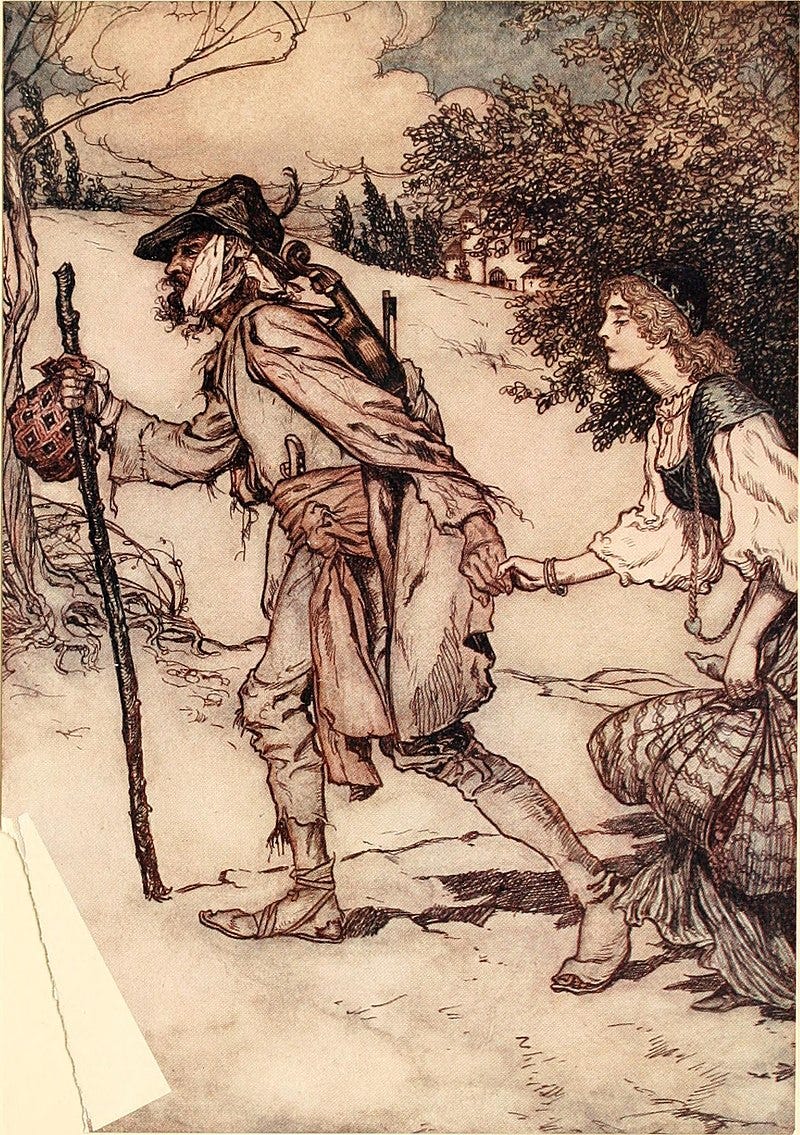

I was like the haughty princess in “King Thrushbeard,” as grimly misogynist a tale as folklore’s founding Brothers ever shaped for posterity. When marriageable suitors come to call, each one a baron at the least, the princess waves them off with insults. She saves her worst for a king whose chin she laughingly compares to “the beak of a thrush.” Her cruelty so offends her father, a king in his own right, that he vows to make her pay for the rest of her life. He gives her away to the first beggar at the door, who sets her weaving and scrubbing like the lowest of scullery maids.

Okay, so the princess has some growing up to do. But the Grimms pile on the humiliations. In their world soft-spoken helpmeets are prized and uppity women singled out for punishment. Only when the princess has well and truly suffered, and been roundly mocked for her incompetence at all things domestic, does the beggar drop his disguise and reveal himself as—you guessed it!—King Thrushbeard, ready to make her his queen. “Then in truth her happiness began,” says my copy of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, a talisman of mine for a lifetime. That line chills me now, although as a child I didn’t question it.

After marriage to one man for my entire adult life, I can say without a doubt that the experience has burnished me. It encouraged me to grow into my generosity and let my inner scold quiet down, if not exactly shut up. Neither of us managed to change the other, doggedly as we tried in the early years. And yet, side by side, we have changed. Like plants turning toward sunlight, we have turned toward possibility. We spot invitations to become gentler versions of ourselves—nowhere near every time, but often enough to make a difference.

I’d known Paul for about three months when it became clear that any place we shared was home—even the roach-infested flat we could barely afford. We fought ardently and made love in the afternoon with the heedless freedom of the intermittently employed. When I decided he should meet my parents in New Hampshire, we hitchhiked there from Toronto, arriving dusty and bedraggled after overnighting in a ditch in White River Junction.

At dinner Paul failed the test my father put to any young man who dared court me or my sister. Max Maynard, a painter of professor of English, had to satisfy himself that we weren’t trifling with philistines. He leaned back in his chair and asked in his seminar voice, with a faint British accent, “What is beauty?” Paul had too much character for a craven spiel (“Your daughter, sir. She’s gorgeous and smart and I’m crazy about her”). Then again, he didn’t have a way with Keats. The right answer, if one existed, must have been “Beauty is truth, truth beauty—That is all/ Ye know on earth and all ye need to know.” My father’s eyes hardened.

It was pie that saved the day. My mother brought out a golden beauty, its crust releasing droplets of raspberry juice. All my life I’d competed for the biggest slice of pie, and raspberry was my favorite, made with plump berries grown in a neighbor’s garden. You couldn’t buy such berries in any supermarket. But when my mother passed me a wedge big enough for two, I handed it to Paul without a second thought. He couldn’t have known what this meant; I barely knew it myself. But my younger sister saw that an earthquake had shaken my heart. She pulled me aside, all aflutter with disbelief: “Rona, you are positively subservient to this Paul Jones.”

Subservience is what King Thrushbeard wanted. Love was what I wanted, and it had arrived with a presence real enough to eat. It had changed me. Someone noticed—someone with intimate knowledge of the Rona who insisted on the biggest of everything, from servings of ginger ale to bedrooms. One of these days I’ll have a go at defining beauty without any help from Keats. But maybe there’s nothing more beautiful than the way love stretches a lover.

Okay, Amazement Seekers. How do you know you’re in love? How much effort will you invest in carrying the emotional load for two while the other person finally decides that yes, this is it? If you happen to know what beauty is, I’m all ears. And if you liked this post, I figure you’ll like this one too.

This is a lovely lovely phrasing of what it means to be in genuine partnership with another: "Like plants turning toward sunlight, we have turned toward possibility. We spot invitations to become gentler versions of ourselves—nowhere near every time, but often enough to make a difference." Thank you, Rona.

Well, talk about delightful! Yes, houses are a lot like people. And our leather-jacket loft was definitely not a keeper for a couple of sexagenarians.