Holding onto You

When life as I had known it died, I held onto a story that set me on the path to vitality.

Sometimes your life ends while you go through all the motions of living. After my mother died, I still chopped garlic, met magazine deadlines, complained to my son about blasting U2 till my ears hurt, as she had once complained to me about an overdose of Dylan. But the moments of my day seemed to float untethered without the prospect of a call from my mother. Could we come for smoked salmon and Negronis? Had I discovered this or that unmissable book?

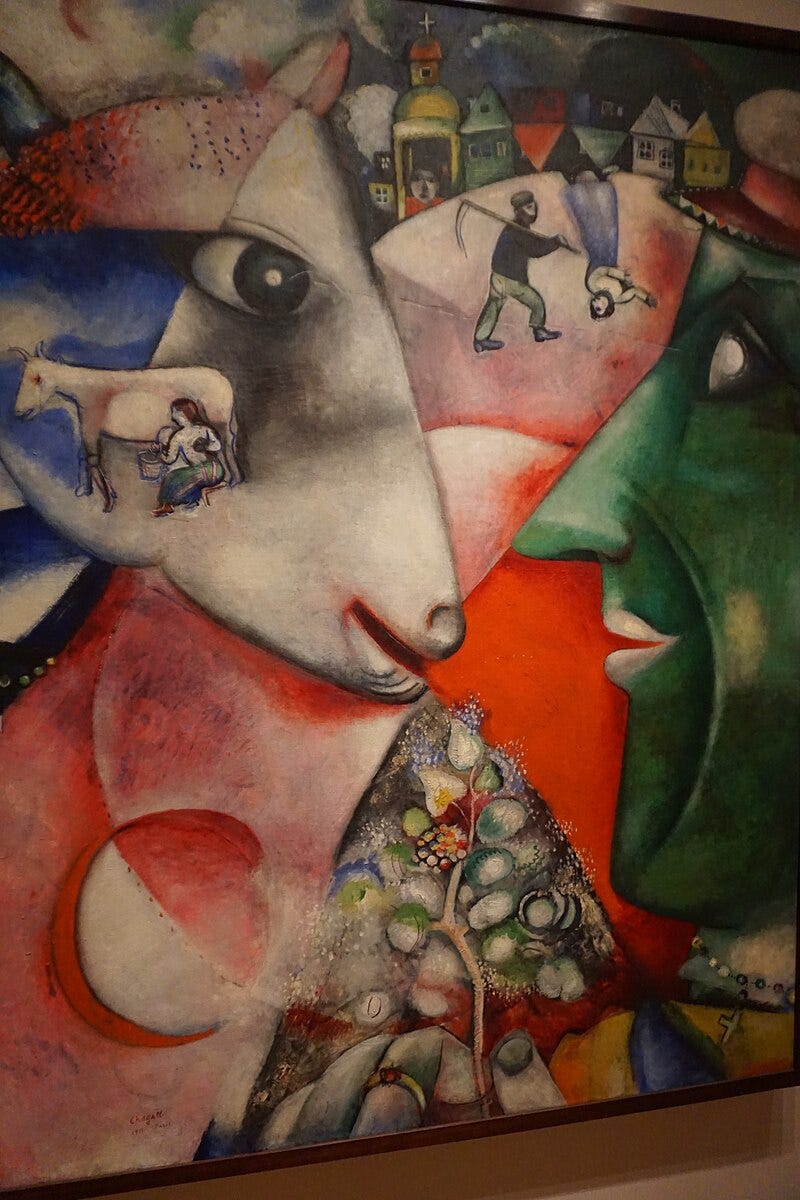

She never mentioned Hasidic Tales of the Holocaust, a yellowed paperback with a Chagall painting on the cover. I came upon it while cleaning out her study. She could write all day in her nightgown when the words flowed and no one was coming to lunch. The book sat within arm’s reach of her IBM Selectric, as if at any minute she might need to anchor a chapter with some remembered line from its pages. Instinct told me it belonged on my bedside table.

Yaffa Eliach, who survived the Holocaust and made her name preserving its history, compiled the book from six years of interviews with other survivors—all Hasidim, the most mystically inclined of ultra-Orthodox Jews. Religious orthodoxies, no matter the faith, have always set me on edge, but storytelling is a high devotion in itself—one I share with the Hasidim. They have cherished the defining power of story since their spiritual movement was born in the 18th century. The stories in Eliach’s book are those the tellers pulled from the ashes of everything they prized except their tradition of ardent and generous-hearted worship.

No one had tried to stamp me out along with all my kind, but my sad, soft existence didn’t feed my craving for purpose.

The first death I grieved was my mother’s. She died in her own warm bed while the man she loved sang to her in Yiddish. The people I met in Hasidic Tales had seen entire families murdered. If starvation and exhaustion didn’t take them, they too could be killed any day. No one had tried to stamp me out along with all my kind, but my sad, soft existence didn’t feed my craving for purpose. Like many readers, I believed Joan Didion’s declaration “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Hasidic Tales promised something more: stories from the real experts on living, those who had returned from the very brink of death.

Some people carry good luck charms in their pocket. I carry the first Hasidic tale in my memory.

Thousands of starving prisoners have just been ordered to leave their barracks and report to an open field. After a frenzied stampede to the field, they confront two enormous pits and a guard who bellows the order: Jump one of the pits to safety, or be shot. The S.S. laugh, the emaciated prisoners cower. A rested and well-nourished athlete would be hard-pressed to make the leap.

A man of no faith turns to his friend, the Grand Rabbi of Bluzhov. Why bother to attempt the impossible? All they will achieve is a moment’s amusement for their captors. Might as well climb into a pit and wait for the end.

Exactly what I’d say myself. But the rabbi won’t hear of giving up. They must obey the will of God.

The two stand on the edge of a pit as body after body falls in amid the gunfire. They close their eyes and jump, then open their eyes to a marvel: They have reached the other side. The freethinker, weeping with gratitude, exclaims that God must exist after all. He asks the rabbi, “How did you do it?”

The rabbi answers, “I was holding on to my ancestral merit. I was holding on to the coattails of my father and my grandfather and great-grandfather, of blessed memory…. Tell me, my friend, how did you reach the other side of the pit?”

Says the friend, “I was holding on to you.”

At our stage of life, the mid-70s, the loss of anything you treasure has deep reverberations.

The last time my life ended, around18 months ago, I thought it wasn’t over, just in need of a tune-up. We lost the dog-friendly bungalow we’d been renting in St. Pete, where we drove every winter from our home in Toronto. We found another place that would suit us nearly as well. Then we lost our dog to cancer.

We were dreaming of road trips south with our next dog when the current U.S. president declared economic war on Canada and threatened to annex our country. Wherever we go next winter, it won’t be Florida. No more dog walks along Tampa Bay, where people watched for dolphins and took wedding vows under the palms. No more impromptu picnics with the best Cuban sandwiches ever. No more seafood runs for fish never seen in Toronto—amberjack, cobia, pompano on our lucky day. An entire winter life, gone.

As losses go, it was pretty small-time. No one was bombing us. But at our stage, the mid-70s, the loss of anything you treasure has deep reverberations. On our last sojourn in St. Pete, Covid got me before I could see two friends who live nearby. It’s not clear if I’ll get another chance.

Yesterday I opened Hasidic Tales to “Hovering above the Pit.” The story, like a poem, unfurls with rereading over time. I’ve been holding it close for 35 years, yet only now do I notice that the rabbi gives no credit to God. He speaks instead of human inspiration: his ancestors. Despite the reverence he inspires in his faith community, he’s a humble and curious man who believes he has something to learn from his friend. It’s the atheist beside him—no, former atheist—who attributes their survival to God.

As my mother said when she learned that she was dying of a brain tumor and not slipping into Alzheimer’s, the scourge of her family and her greatest fear, “How interesting.”

We die not knowing when the living will take heart from our memory.

Stories like this one attract endless cant about “the triumph of the human spirit.” In a culture that exalts individualism, one brave and tenacious human is seen as the font of inspiration. In the story at hand, humans inspire each other. Their community of two embraces ancestors long dead. The capacity to hold on, the story tells us, is part of our common humanity. We die not knowing when the living will take heart from our memory. We hold others up without knowing the difference that we make.

When the rabbi’s friend says, “I was holding onto you,” the reader has seen it coming. The rabbi has not. And it is he, one Israel Spira, who will tell the story in Brooklyn to a student of Yaffa Eliach on January 3, 1975. The story lets you see for yourself that the Grand Rabbi of Bluzhov was in awe.

Just now, I Googled his name. He died on October 30, 1989, 27 days after my mother. At 99, he had been the oldest living Hasidic rabbi.

For nearly 20 months, I’ve been meeting readers here on Sunday morning. I haven’t missed a Sunday yet. It could happen, I suppose, but I like knowing you expect me. Many posts no sooner drop than one of you clicks the heart, and then another. “I needed that,” someone says, as if she’s holding onto me. Then someone else is moved to share a story. Stories fall like ripe apples into open hands. My words shook them loose, wind ruffling the tree. Holding onto another person’s story can be all the permission you need to release your own.

Hemingway said, in A Moveable Feast, that everything he wrote began with one true sentence. If he could write one, he could write another one. I know the feeling. It pulls me forward. But so does the presence of one true reader I may never meet face to face. My one true reader may live across town or across an ocean. If I can find one, I can find another one. I can’t make out the contours of the next life I’m making. Here’s a window. Over there, a fireside. Two chairs that could be any style you like.

True reader of mine, perhaps you’ve seen this coming. I am holding onto you. In awe.

Your turn, true readers new and old. Who or what are you holding onto these days as certainties crumble all over the world? Pull up a chair. Let’s get this conversation started. I promise to answer every comment.

The beauty of holding is reciprocity. My amazing sister Joyce and I have held onto each other for more than 70 years. We’ve done some pushing away, but that’s long over. I’m excited to tell you Joyce has come to Substack. You’ll find her first story here.

Substack writers have inspired me ever since I landed here. A few recent discoveries:

Elizabeth Beggins shows how a kind comment in the produce aisle can be an act of resistance;

Ann Richardson asks why we’re shocked when a mother teachers her little girls to call the part between their legs by its true name, the vulva;

Holly Starley has a reckoning with one black bear and the wild thing in various men;

Nan Tepper explains why the hardest thing about a big body is trying to hide it—and yourself—from the world.

All my stories are free to read. Paid subscriptions are like rainbows.

Damn it, Rona. This morning I woke up groggier than usual (a tough yoga class yesterday), forgot that it was our wedding anniversary (we both did - at 62 years married, it really doesn't matter much - we did remember an hour later and Ray said, with his usual British humour, that all in all I had been a pretty good wife all these years)) and I thought perhaps, just perhaps, I will give Rona a miss this week.

But I couldn't resist the little peek and, of course, was captured, once again, by it all. I didn't know the story, but I liked the sentiment you so beautifully built up. AND then, something caught my eye at the bottom and I went to see what it was and there you are, being so generous again.

For anyone who doesn't know this, Rona Maynard is not only one of the best writers on Substack but also one of the most generous.

Thank you.

This week I heard a quote that I’ll treasure. It may be well known. I’d never heard it. Its spirit echoes what you’ve captured so eloquently here.

“We are all walking each other home.”