Comfort Me with Onions

Renoir loved the joys of the bed and the table. For him the humble onion was a thing of sensual beauty.

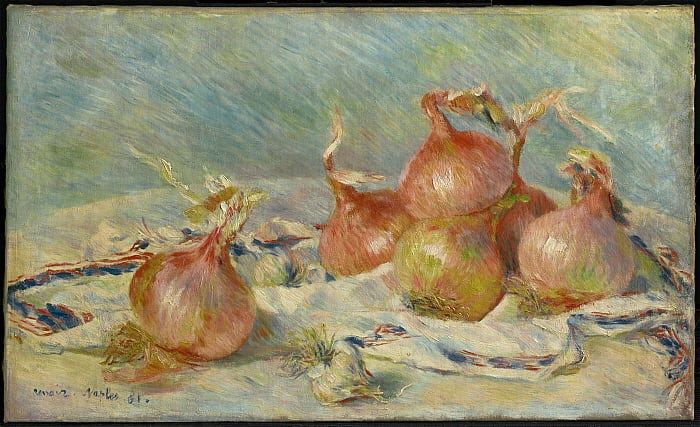

Something comes over me in an art museum—the anticipation of rapture. Any minute I’ll be smitten by a painting. It won’t have a wall of its own or a bevy of fans taking selfies. I’ll know it by the thrum of connection between the painter’s eyes and my heart. I will silently tell this painting, “I’d like to take you home.” At the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass., the painting I want for my own is Renoir’s tumble of onions on a kitchen towel.

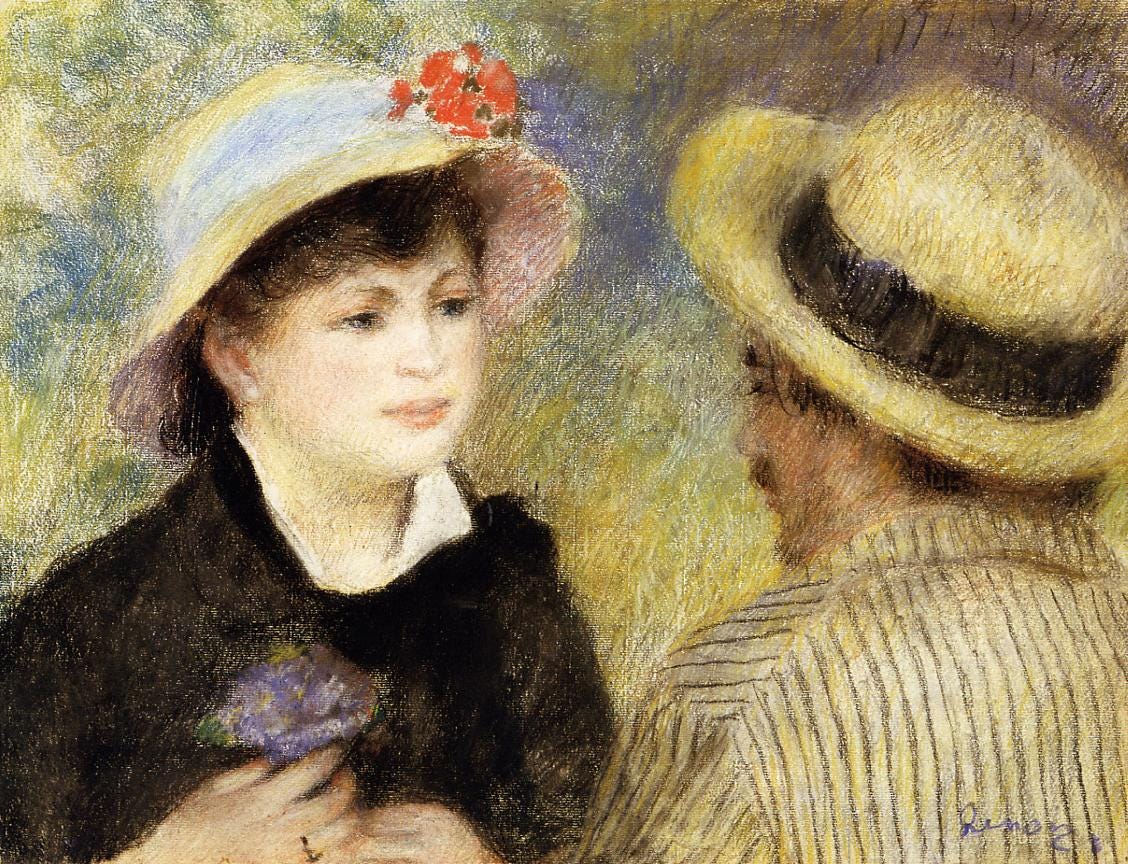

Renoir was the unabashed celebrant of prettiness. A picture, he declared, “should be something pleasant, cheerful and pretty. Yes, pretty! There are too many unpleasant things in life as it is without creating still more of them.” Other museums own more compelling riffs on Renoir’s perennial themes, lush nudes and petal-cheeked girls. To my knowledge, the Clark has the master’s only onions—among the few onion paintings I’ve found anywhere. Why do apples and grapes get all the painterly attention? These onions appear to dance, tossing their stem ends like loosened hair. They radiate the master’s joy in the shimmer and heft of the culinary workhorse that powers every stew.

If an onion grew in the Garden of Eden, it would have looked like these. And God might have said, “Hands off the onion.”

In distant times and places, onions had a mystique. Ancient Greek athletes in search of an edge ate up to a pound of onions and rubbed their skin with onion for good measure. Ramses IV was mummified with onions in his eye sockets. The late cookbook author Bert Greene wrote of those who grew the first onion, some 5000 years ago in Central Asia, “Where an onion bloomed, a temple was erected. Where an onion withered, the land was considered fallow and not even beasts of the field were permitted to graze. Yet… no resident seems to have ever chomped or sautéed a slice. For in the Eastern view, the [onion] with its myriad layered skins was regarded as a symbol of eternity,… far too celestial for mere human consumption.”

Who looks for transcendence in the onion anymore? From the scallion to the leek to your basic yellow orb, it’s all about flavor, all over the world. No onions, no biryani, no pad thai, no Peking duck, no ragu scenting the kitchen. No sweet-and-sour meatballs from my grandmother’s signature recipe. When my husband and I first moved in together, he expressed surprise that “everything you cook has onions in it.” Well, of course. I owned a cookbook in which Craig Claiborne, then food maven of The New York Times, told the truth about the stalwart onion. If ingredients were priced according to the flavor they impart, nothing would be more dear. I could cook decent meals without saffron, truffles or any other frippery beyond our lean budget. Without onions? Inconceivable.

Renoir understood the pleasures of the table. His wife and model, Aline, was an exuberant cook who could stretch a main course to feed a party of hungry painters. She had a free hand with onions. For “Aline’s great triumph,” as the family called her chicken sauté with olives and cognac, she didn’t brown her chopped onions but tossed them straight into the pot. When Renoir painted onions, could he taste the heady broth?

He was the most sensual of painters. Looking at his onions, I can practically feel one in my hand, the crisp skin tight against the glistening flesh. What he did for the curve of a breast, he also did for his voluptuous onions. Some have called him crude for saying, “I paint with my prick.” Some convict him of reducing women to objects of sexual delight. I think he was declaring, with more bravado than finesse, that painting is an act of love. So is making art of any kind. It demands passionate absorption in whatever moves the artist to create. If the creator doesn’t care, why should anyone else?

M.F.K. Fisher, a sensualist with her pen and creator of the food memoir, might be called the Renoir of prose. Like Renoir, she took her knocks for her focus on pleasure. In The Gastronomical Me, first published in 1943 and a touchstone of mine, she answered critics who “accusingly” suggested she should turn her gifts to a more worthy subject. “It happens that when I write of hunger, I am really writing about love and the hunger for it, and then the warmth and richness and fine reality of hunger satisfied, and it is all one.”

Neither Fisher nor Renoir had it easy. Fisher reached a great age and continued to write after the excruciating illness and death of the man she loved more than any other. Rheumatoid arthritis could not stop Renoir. When his hands became deformed fists, he had his brush affixed between the knuckles, wrapped in cloth to prevent sores. He worked in his wheelchair, a cat snuggled in his lap to keep him warm. Pain sharpened his pleasure in beauty wherever he found it. He left some 4,000 paintings, each one a love letter to the world.

It's been a while since I last found a yellow onion worthy of Renoir. Winter is the season for big pots of onion-laced comfort, yet a slimy winter onion, if you're not careful, can cause the knife to slip. Next thing you know, you’re cleaning a wound instead of stirring onions in your fat of choice till they glow and turn sweetly pungent. My mother taught me not to rush the onions, but sometimes I forget. In my distraction with lawlessness and vengeance in the news, my impatience with the bitter weather, my sorrow for the dog no longer at my feet, waiting for a crumb of cheese to fall, I let the onions char.

The other night I simmered up a pot of chicken and red lentil soup. Two ample sautéed onions and a handful of garlic melted into the aromatic broth. When things fall apart, a bracing meal unites the fragments for a while. “Onion” comes from the Latin “unio,” one. If I could serve my soup to the Renoirs, I’m pretty sure they’d approve. But my husband told me twice how good it was. Then we had seconds and tasted the fine reality of hunger satisfied.

Let’s get your taste buds tingling. Is there a meal you crave in dark times? A recipe you love that wouldn’t be the same without an onion? What is it about comfort food, anyway? Renoir fans (or foes), you jump in too. I’ve had my issues with Renoir’s prettiness fixation, but he’s grown on me lately. How about you?

Onion fanciers, have I got a book for you: Mark Kurlansky’s The Core of an Onion. Two kinds of onions embolden my favorite recipe: Beef Cheeks Bourguignon. Art-minded readers, you’ll find lots to explore right here. Bonnard, anyone? How about Degas’ Little Dancer? I love to see readers poke around—that’s why you won’t find any paywalls here.

If you’re among my many new readers, you’ll find a change of pace next week. I celebrate amazement all over the emotional map, and my community likes it that way. I’m deeply grateful for your shares, likes and comments—each one a sign that my words made a difference to you. That’s what I’m here to do, and you’re the ones who know if I’ve done it. Some readers of heart and means have chosen paid subscriptions, just because they believe in my work. If you are so moved, I’d be honored. No pressure, though. We’re friends either way, and you can’t buy friendship.

This brought to mind how six large onions, with the help of salt, pepper, and paprika, can magically turn a piece of brisket into savory heaven! My favorite winter meal of all time!

A wise teacher began every watercolor class with this, written on the whiteboard, “Art=Emotion". I know this as a painter and an observer. When artists paint to please themselves, the emotion is felt and often takes the viewer by surprise. It is, in fact, what makes a person open their wallet and decide they must have a work of art as it speaks to them. In our household, since he retired, it seems my husband cooks up onions for almost every meal. I sometimes complain how the house smells like onions but now have a new appreciation for his palate and his willingness to do more than his share of cooking. I look forward to Sunday as your weekly posts bring joy and flavor, literally, to an otherwise unsettling world. Thank you.